¶ (Radio)Isotope Power Systems

- 2IPS - (Radio)Isotope Power Systems

- Short video introducing technology:

¶ 1. Roadmap Overview

Radioisotope Power Systems (RPS) are specialized energy systems that convert the heat released from the radioactive decay of isotopes into usable electrical power. They use solid-state conversion technologies such as thermoelectric or photovoltaic converters.

The process begins with the decay of a radioisotope source. This decay generates heat. The heat is transferred through thermal interfaces and encapsulation to a solid-state converter. The converter transforms thermal energy into electrical energy. The output can then be stored or consumed by a connected device.

.jpg)

RPS technologies provide reliable and maintenance-free power in environments where conventional energy sources cannot be used. Examples include deep-ocean and subsea systems, polar and under-ice research stations, and hazardous industrial facilities. They also support long-duration autonomous vehicles, unattended environmental monitoring networks, and defense applications such as persistent surveillance and communication nodes. In these environments, sunlight, refueling, or maintenance are often not possible. RPS provides continuous electrical power for years or even decades without human intervention.

This Level 2 technology roadmap focuses on the product-level development of RPS. It examines how improvements in radioisotope selection, decay energy use, converter efficiency, and thermal management improve overall system performance. The roadmap focuses on Figures of Merit such as power density, efficiency, lifespan, and reliability. By tracking these measures, we can see how technical advances in components increase mission reach, reduce operational risk, and extend service life in scientific, industrial, and defense applications.

From an innovation perspective, RPS development represents an incremental sustaining innovation. The technology builds on a proven principle: converting heat from isotope decay into electricity. Advances in materials, conversion efficiency, and safety engineering improve performance and reliability without changing the basic system design. These improvements sustain and extend current applications rather than creating a disruptive shift in the energy sector.

The roadmap defines a development path toward next-generation RPS architectures. Future systems will have higher power-to-mass ratios, longer lifespans, and better conversion efficiency. These systems will support long-term operation of critical scientific, industrial, and defense technologies in remote, extreme, and hazardous environments on Earth.

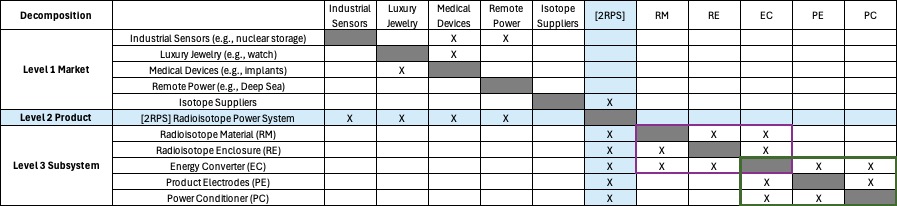

¶ 2. Design Structure Matrix (DSM) Allocation

(interdependencies with other roadmaps)

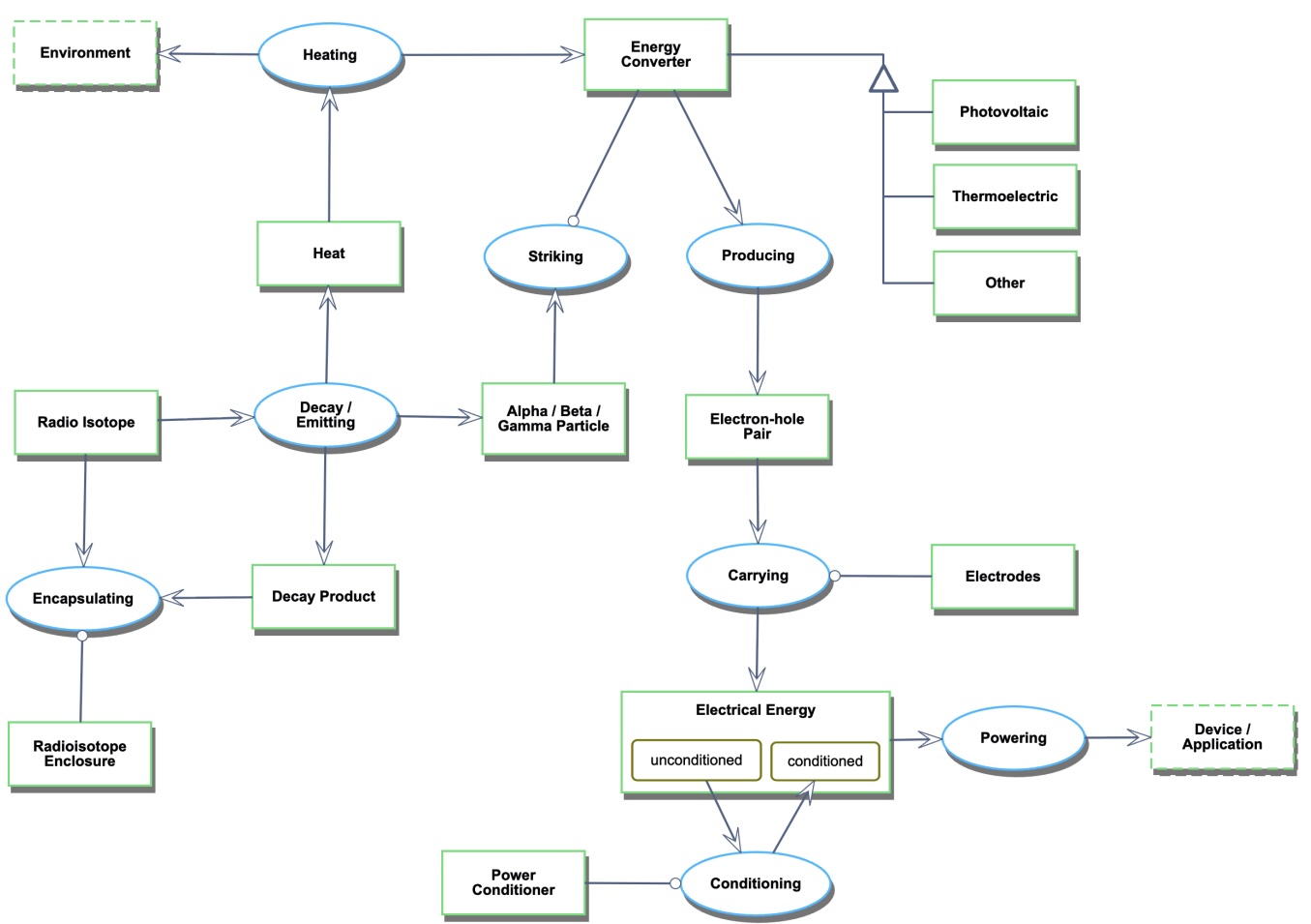

¶ 3. Roadmap Model using OPM

(ISO 19450)

1. Radioisotope Enclosure is a physical and systemic object.

2. Radio Isotope is a physical and systemic object.

3. Alpha / Beta / Gamma Particle is a physical and systemic object.

4. Energy Converter is a physical and systemic object.

5. Electrical Energy is a physical and systemic object.

6. Electrical Energy can be conditioned or unconditioned.

7. Device / Application is a physical and environmental object.

8. Heat is a physical and systemic object.

9. Photovoltaic is a physical and systemic object.

10. Thermoelectric is a physical and systemic object.

11. Electron-hole Pair is a physical and systemic object.

12. Environment is a physical and environmental object.

13. Decay Product is a physical and systemic object.

14. Electrodes is a physical and systemic object.

15. Power Conditioner is a physical and systemic object.

16. Other is a physical and systemic object.

17. Other, Photovoltaic, and Thermoelectric are Energy Converters.

18. Encapsulating is a physical and systemic process.

19. Encapsulating requires Radioisotope Enclosure.20. Encapsulating consumes Decay Product and Radio Isotope.

21. Decay / Emitting is a physical and systemic process.

22. Decay / Emitting consumes Radio Isotope.

23. Decay / Emitting yields Alpha / Beta / Gamma Particle, Decay Product, and Heat.

24. Striking is a physical and systemic process.

25. Striking requires Energy Converter.

26. Striking consumes Alpha / Beta / Gamma Particle.

27. Carrying is a physical and systemic process.

28. Carrying requires Electrodes.

29. Carrying consumes Electron-hole Pair.

30. Carrying yields Electrical Energy.

31. Conditioning is a physical and systemic process.

32. Conditioning changes Electrical Energy from unconditioned to conditioned.

33. Conditioning requires Power Conditioner.

34. Powering is a physical and systemic process.

35. Powering consumes Electrical Energy.

36. Powering yields Device / Application.

37. Heating is a physical and systemic process.

38. Heating consumes Heat.

39. Heating yields Energy Converter and Environment.

40. Producing is a physical and systemic process.

41. Producing consumes Energy Converter.

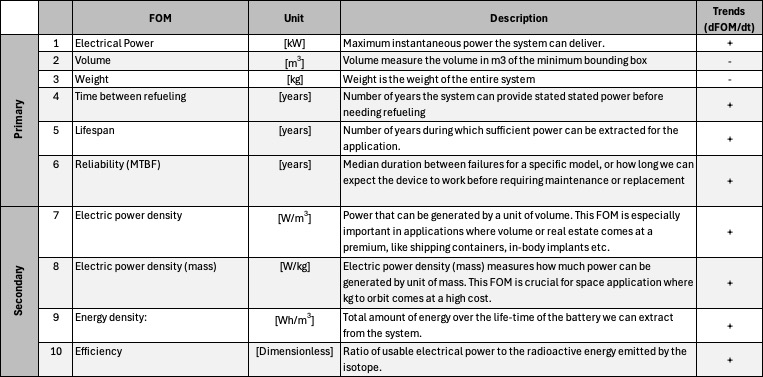

¶ 4. Figures of Merit (FOM)

(Definition, name, unit, trends dFOM/dt)

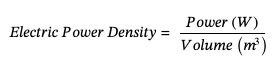

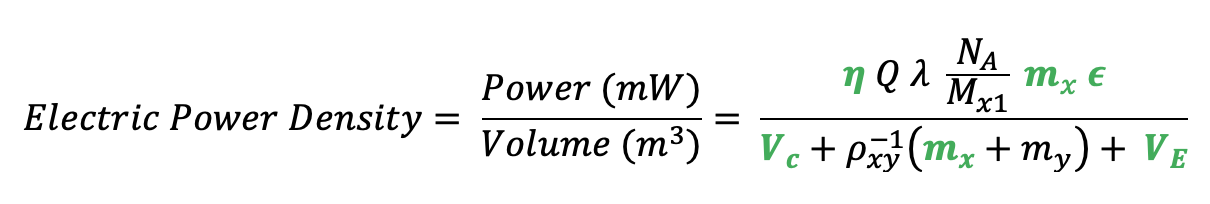

¶ FOM 1: Electric Power Density (Volume)

Electric power density (volume) measures how much power can be generated per unit of volume. This is important when available space is limited, such as sealed systems or compact payloads.

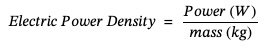

¶ FOM 2: Electric Power Density (Mass)

Electric power density (mass) measures how much power can be generated per unit of mass.

This is critical in applications where mass directly affects deployment cost or mobility.

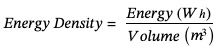

¶ FOM 3: Energy Density (Wh/m³)

Energy density is the total amount of electrical energy produced by the system over its operational life per unit of volume.

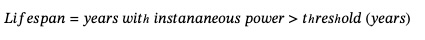

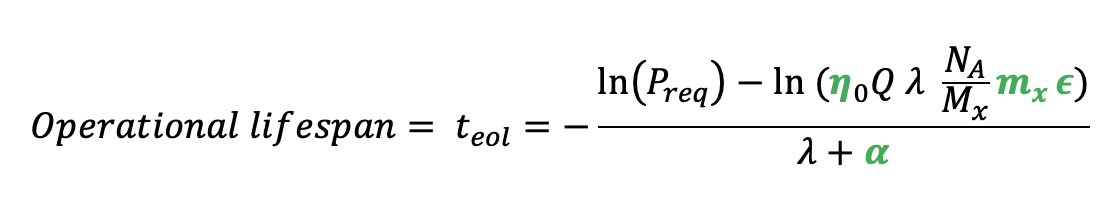

¶ FOM 4: Lifespan (Years)

Lifespan measures the number of years during which the system delivers sufficient power above the operational threshold.

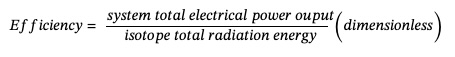

¶ FOM 5: Efficiency (Dimensionless)

Efficiency is the ratio of usable electrical power to the radioactive energy emitted by the isotope.

¶ FOM 6: Reliability (MTBF)

Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) measures the average time the system operates before a failure occurs.

¶ FOM 7: Electrical Power (kW)

Electrical power is the instantaneous output available from the system.

¶ FOM 8: Volume (m³)

Volume refers to the minimum bounding box of the system and all contained components.

¶ FOM 9: Weight (kg)

Weight is the total system mass.

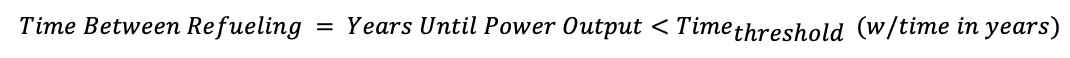

¶ FOM 10: Time Between Refueling (Years)

Time between refueling represents how long the system operates before the power output drops below threshold and refueling is required.

¶ 5. Alignment of Strategic Drivers: FOM Targets

These technology targets are designed to strengthen the organization’s position in long-duration, high-reliability RPSs while supporting strategic goals of sustainability, miniaturization, and operational resilience. Projected advancements are expected to significantly enhance system performance across multiple Figures of Merit (FOMs):

Conversion Efficiency (FOM-1): Increase from 5% → 15% (3× improvement) to raise overall energy output per isotope mass.

Enclosure and Converter Volume (FOM-2): Reduce by 10%, improving compactness and energy density for smaller, deployable power modules.

Fuel Enrichment (FOM-3): Increase to 100% to maximize isotopic purity and power conversion efficiency.

Alpha (Degradation Rate) Parameter (FOM-4): Reduce by one-sixth (≈ 17%) to extend operational stability and device lifetime.

Material Density (FOM-5): Incorporate q-Carbon, a novel allotrope up to 60% denser than conventional carbon, to enhance structural performance and packing efficiency.

Collectively, these improvements are projected to yield measurable system-level gains:

Power Density: 0.542 mW/cm³ → 2.6 mW/cm³

Operational Lifespan: 414 years → 700 years

Together, these FOM targets align with the organization’s strategic drivers of high-endurance, safe, and sustainable energy technologies, positioning it for leadership in ultra-long-life power applications such as remote sensing, space systems, and autonomous infrastructure.

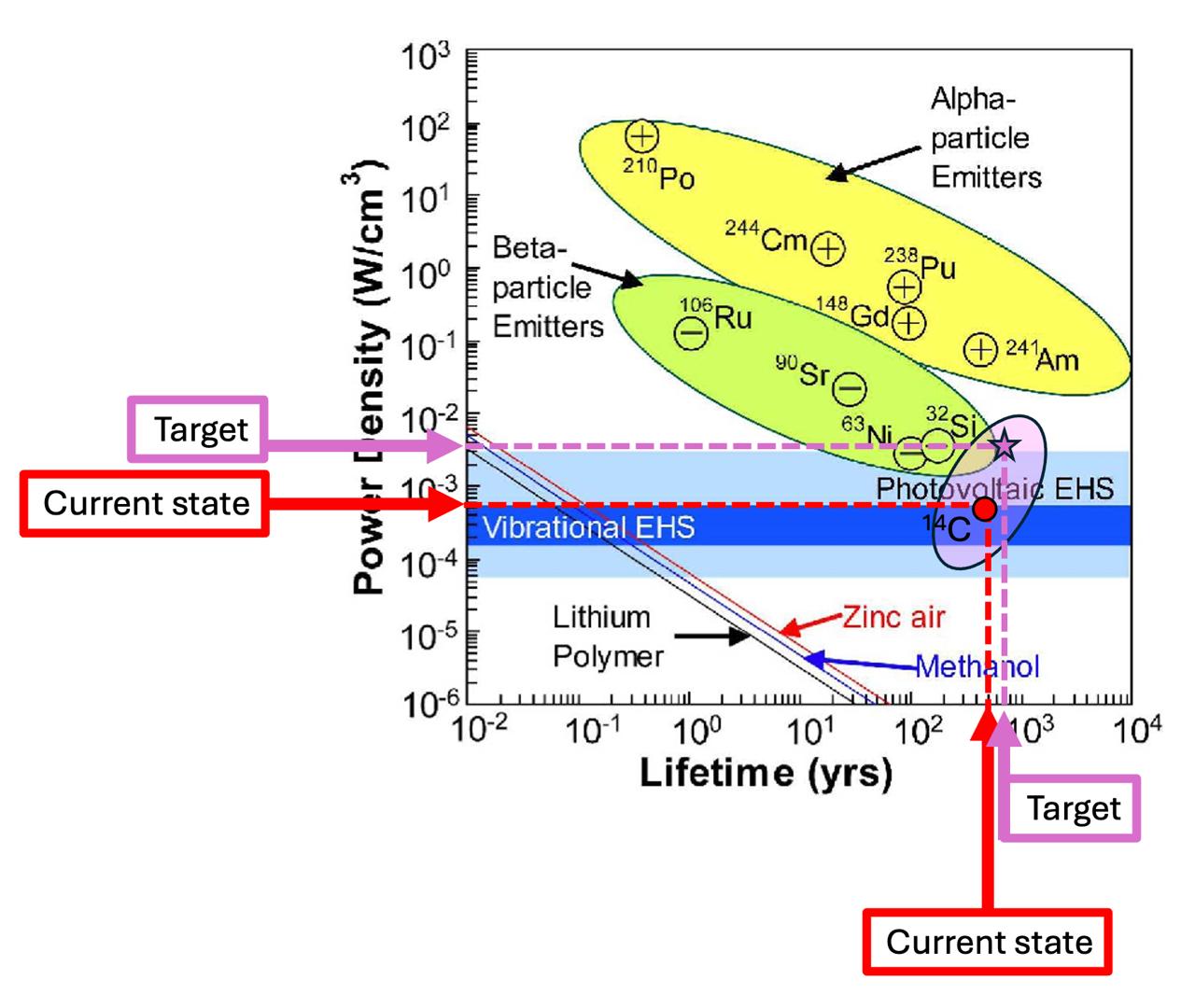

¶ 6. Positioning of Company vs. Competition: FOM charts

This section compares the organization’s projected performance against competing energy technologies through key Figures of Merit (FOMs)—including power density, lifespan, safety, and sustainability. Although detailed quantitative FOM charts will be developed in subsequent roadmap iterations, the following discussion outlines the organization’s competitive advantages within the rapidly evolving field of long-duration, maintenance-free power systems.

¶ Competitive Landscape Overview

The global long-duration energy market is growing rapidly, driven by demands for autonomous, sustainable, and reliable power in sensors, medical implants, space systems, and industrial IoT. Competing technologies generally fall into four primary categories:

- Conventional Batteries (e.g., Li-ion, solid-state):

Dominant in consumer and industrial devices, offering high instantaneous power but limited lifespan (3–10 years) and capacity fade from chemical degradation. - Micro Energy Harvesters (solar, vibration, thermal):

Environmentally clean but intermittent, dependent on ambient energy sources, and unsuitable for sealed or remote systems requiring continuous operation. - Legacy Isotopic Systems (e.g., Plutonium-238 RTGs):

Proven for aerospace and deep-space applications, but radiologically complex, heavy, and expensive, with lifespans of 80–100 years and strict handling requirements. - Modern Betavoltaics (e.g., Nickel-63, Tritium):

Compact and relatively safe, but limited by shorter half-lives (12–100 years) and restricted isotope availability, requiring periodic replacement and controlled reactor production.

Amid these limitations, the Carbon-14 diamond battery establishes a fifth category—a commercially scalable, ultra-long-life, and environmentally responsible power platform that combines nuclear longevity with advanced materials engineering.comp

¶ Strategic Differentiation: Why a Carbon-14 Battery?

The organization’s defining advantage originates from its deliberate selection of Carbon-14 (C-14) as the core radioisotope. This choice yields superior performance across nearly every FOM—especially lifespan, safety, and sustainability—and provides a unique competitive position in the next generation of ultra-long-duration energy systems.

- Ultra-Long Lifespan:

Carbon-14’s 5,730-year half-life enables continuous power generation for millennia, far exceeding the operational lifespan of Nickel-63 (~100 years), Tritium (~12 years), or Plutonium-238 (~80 years). - Safety and Containment:

Carbon-14 emits low-energy beta particles easily absorbed by solid materials. When embedded in diamond encapsulation, the isotope remains fully contained and requires minimal shielding, making it safe for medical, aerospace, and industrial environments. - Environmental Sustainability:

The manufacturing process upcycles reactor graphite waste, converting Carbon-14 from a nuclear byproduct into a valuable clean-energy source and contributing to radioactive waste reduction. - Zero Emissions and No Hazardous Byproducts:

Carbon-14 diamond batteries produce no greenhouse gases or chemical waste. Unlike lithium or cobalt systems, the isotope is not mined or extracted from the environment, aligning with circular-economy principles. - Chemical and Thermal Stability:

Diamond encapsulation provides exceptional resistance to chemical degradation and thermal extremes, ensuring reliability even in harsh or remote conditions.

C. D. Cress, B. J. Landi and R. P. Raffaelle, "Modeling laterally-contacted nipi-diode radioisotope batteries," 2008 IEEE Long Island Systems, Applications and Technology Conference, Farmingdale, NY, USA, 2008, pp. 1-8, doi: 10.1109/LISAT.2008.4638957.

¶ Summary

The organization’s use of Carbon-14 as a radioisotope establishes a distinct competitive advantage: an ultra-safe, ultra-sustainable, and millennia-scale energy system that redefines the performance envelope for commercial long-duration power.

These attributes position the company as a leader in the emerging market for self-powered, maintenance-free technologies supporting next-generation IoT, aerospace, medical, and autonomous platforms.

¶ 7. Technical Model: Morphological Matrix and Tradespace

¶ Morphological matrix

The morphological matrix defines the key architectural and design variables influencing the performance of the radioisotope power system. Each row represents a critical design function, while each column enumerates viable technical options under current or near-term manufacturing capabilities. Together, these combinations outline the design space from which candidate system architectures can be synthesized and evaluated against Figures of Merit (FOMs) such as power density, operational lifespan, safety, and sustainability.

| Function | Option A | Option B | Option C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotope | C-14 (low-E β) | Ni-63 | Pm-147 |

| Emitter geometry | Planar CVD diamond | Porous diamond (higher self-absorption use) | Pillar/mesa arrays |

| Junction | p-i-n diamond | Schottky | Hetero-diamond/DLC |

| Encapsulation | Diamond/DLC | AlN/SiC cap | Metallized polymer |

| Electronics | ASIC µW readout | Discrete low-leakage | Energy harvester + buffer |

| Package | Hermetic ceramic | Metal can | Polymer overmold |

(Porous/embedded C-14 can improve coupling efficiency by reducing self-absorption path lengths; see recent literature.)

¶ Tradespace

The following dives into the trade space analysis by focusing on the isotope selection in the morphological matrix section. The isotopes observed include Tritium (H-3), Nickel-63 (Ni-63), Strontium-90 (Sr-90), Americium-241 (Am-241), Carbon-14 (C-14), and Promethium-147 (Pm-147). At first, we look at how theoretical specific power in terms of Watts per gram performs against isotope costs per gram shown below.

Specific power and material costs were first investigated to produce a simple figure that shows scalability according to power needs (i.e., the system needs X power, therefore requiring Y grams of [isotope], which would cost Z dollars). The figure illustrates a utopia point, represented by the golden star, and a Pareto front, indicated by the dotted line. At first glance, Pm-147 appears to be both affordable and powerful. However, the costs depicted in the table are unreliable as the isotope market currently does not serve the potential RPS market or has an outdated price. For example, current uses for these isotopes include calibrating analytical instruments. Furthermore, power from an RPS is scalable, and the importance of costs varies depending on different consumer needs. The specific power and financial costs tell a small, fuzzy part of the story.

Instead, the tradespace for taking RPS to commercial uses takes a broader approach by investigating characteristics of producibility and marketability in each isotope. Furthermore, both producibility and marketability are broadly functions of affordability, acceptability, capability, accountability, usability, and manufacturability. These -ilities for the purpose of this roadmap are defined below.

-ilities:

- Marketability – The ability to fulfill societal needs and establish a product into the market.

- Affordability – The measure of life-cycle cost; primarily driven by current costs and potential to lower isotope costs.

- Acceptability – The broad concept that accounts for various sociotechnical factors; primarily driven by public taboos.

- Capability – The expression of isotopes' ability to achieve a specific objective; primarily driven by power density.

- Producibility – The ability to produce the desired isotopes and integrate them into a working RPS.

- Accountability – The obligation of organizations to accept responsibility; primarily driven by regulations.

- Usability – The extent to which the isotopes can be handled by trained users to achieve specified goals.

- Manufacturability – The ease with which the isotopes can be acquired; primarily driven by isotope generative sources.

These -ilities for the chosen isotopes were given a score rating out of five, with five being the most favorable score for each characteristic. The score for each -ility was determined by an AI tool and charted by the radar chart below.

The radar shows that each isotope performs differently with respect to each -ility. These –ility scores were then weighted. Producibility for each isotope weighs the sum of accountability, usability, and manufacturability, while marketability weighs the sum of affordability, acceptability, and capability. These factors were then used to produce the figure below. The figure shows a utopia point, represented by the golden star at the top right, and a Pareto front, provided by the dotted line.

The figure shows that it is less clear which isotope is the leading isotope to focus on for commercial use.

Future Exploration:

Future exploration would incorporate additional isotope candidates for RPS.

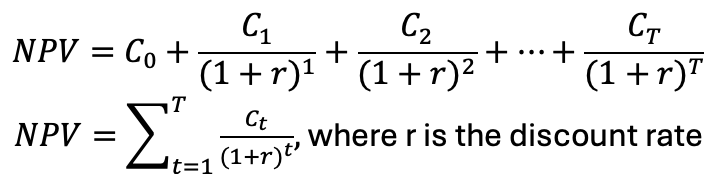

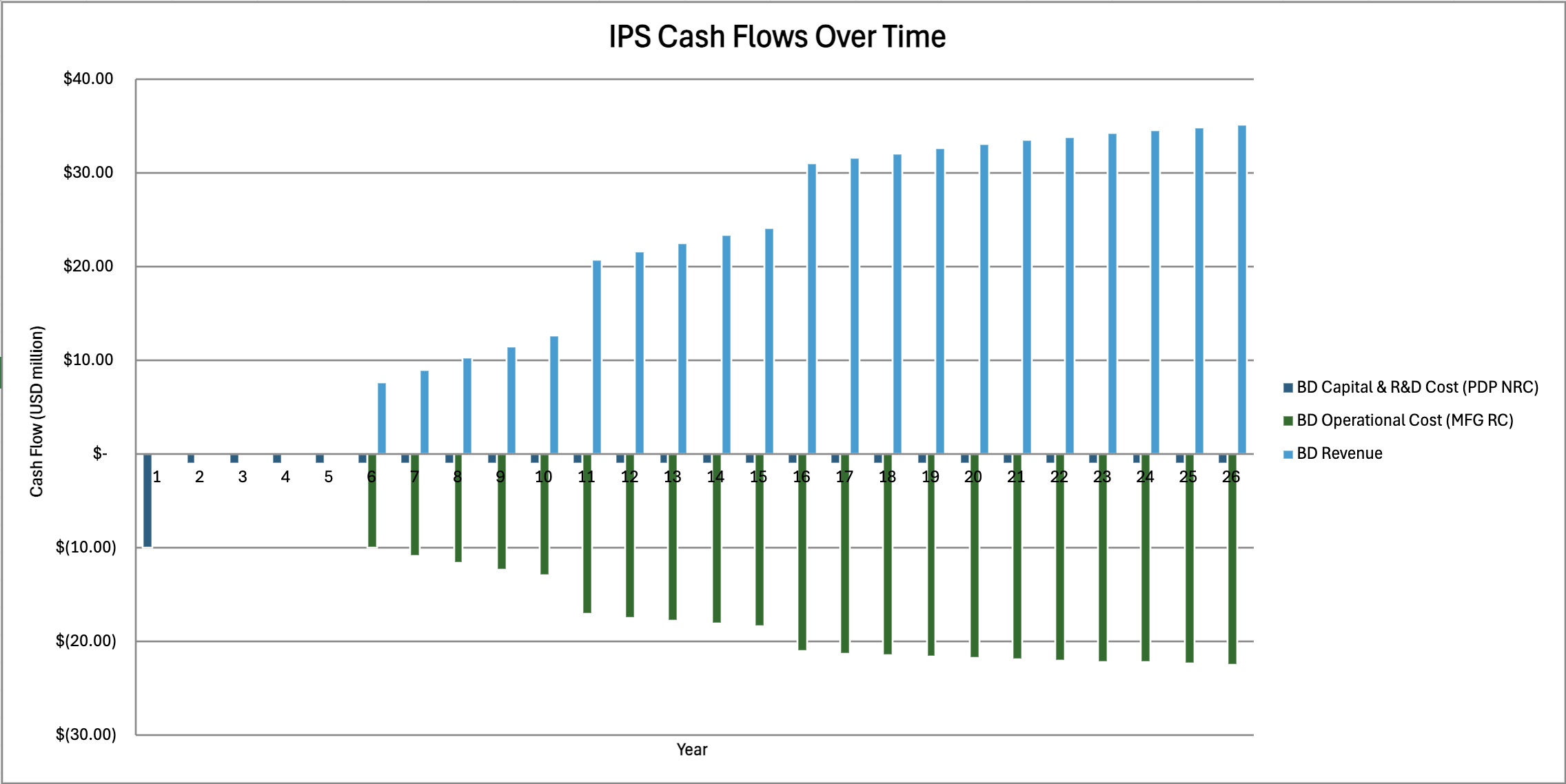

¶ 8. Financial Model: Technology Value (𝛥NPV)

The figure below summarizes the NPV analysis for RPS. It includes the non-recurring development cost (NRC) incurred between 2025–2030, the revenue ramp beginning in 2026, and a long-run plateau extending through 2050 as RPS devices are deployed in remote IoT and long-duration sensing markets. The parameters and values listed below were used to construct the financial model.

Value has to be generated for two key stakeholder groups:

Value to customers (based on performance attributes, uptime reliability, and avoided maintenance/fuel logistics)

Value to shareholders (based on discounted profits and positive NPV over time)

The governing equations for NPV are shown below.

¶ Parameters Used in the Financial Model

The following parameters specify the core assumptions used to construct the financial model, including development costs, manufacturing behavior, market conditions, and the discount rate applied to future cash flows. Together, these inputs determine the lifecycle cash flows and the resulting net present value of the RPS program.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Program Start Year | 2025 |

| Product Development Budget (NRC) | 16 to 28 million USD (20 million midpoint) |

| Product Development Time [yrs] | 5 |

| Unit Manufacturing Cost | 0.8 to 1.2 million USD per device |

| Entry Into Service (EIS) | 2030 |

| Total Market Size in 2030 | 50 to 150 million USD |

| Addressable Subsegment (SAM) | 20 to 40 million USD |

| Expected Market Share | 10 to 40 percent (25 percent midpoint) |

| Revenue Ramp Period | 2026 to 2035 |

| Production Duration | 2035 to 2050 |

| Discount Rate | 12 percent |

| Financial Units | USD millions |

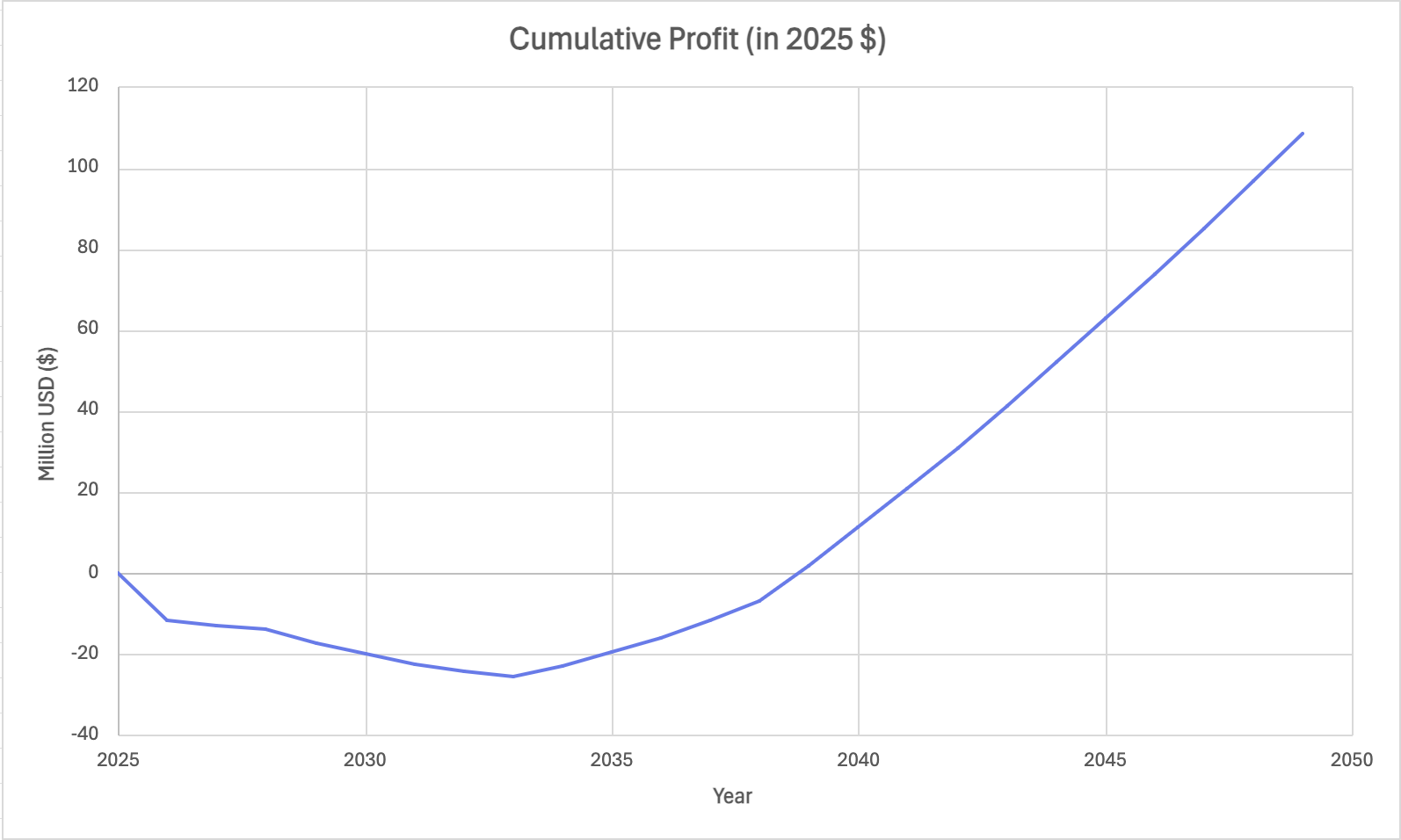

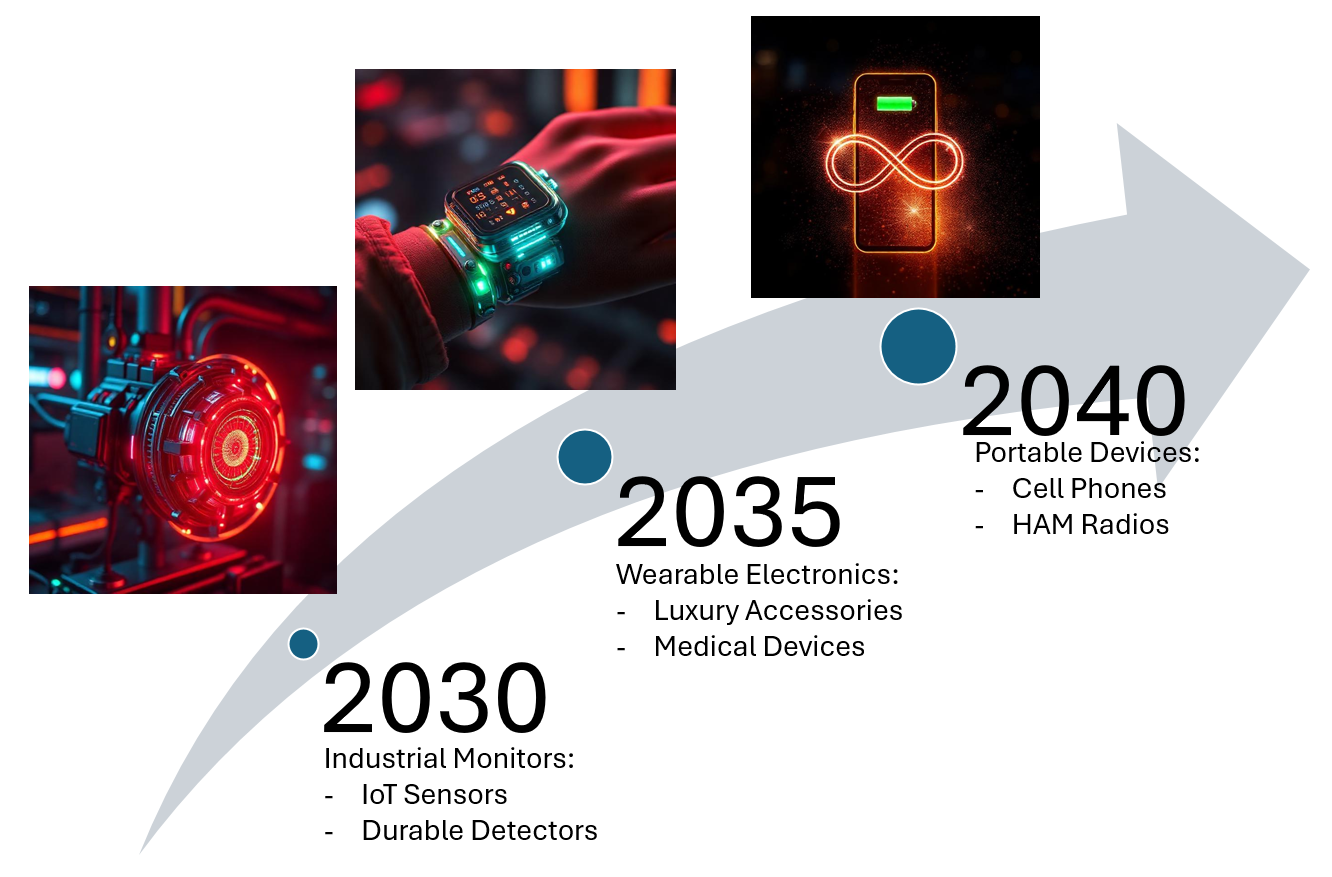

¶ Result of the NPV Analysis

All cash flows from 2025 through 2050 were discounted at a rate of 12 percent. A market analysis report served as the basis for the NPV analysis. Key numerical values from the report include a market valuation of $170.7 Million USD in 2025, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.65%. The NPV assumes the CAGR remains constant over a 25-year period. The NPV starts generating revenue in 2030, following our technological targets for the working product. In 2030, we will enter the IoT market. We will enter the wearable electronics (including medical devices) in 2035 and the portable devices market in 2040 as described in our technology strategy statement. The projected revenue is a function of the forecasted market value and our forecasted market shares. Our initial operational cost and initial investments (including capital and R&D) were estimated. However, the operational costs grow 40% less than the revenue growth using conservative assumptions. The forecasted faster growth rate of revenue suggests that annual profits will become positive in 2035. Furthermore, this suggests we have a 15-year payback period.

RPS therefore produces positive lifecycle value after the initial development phase. The value comes from avoided fuel transport, the elimination of maintenance missions, and stable long-duration operation in environments where conventional systems perform poorly.

In summary, this investment becomes profitable in 2035. By 2040, the initial development cost will have been fully recovered.

¶ 9. List of R&D Projects and Prototypes

Emerging betavoltaic technologies open pathways far beyond traditional device improvements, which generally focus on incremental gains in semiconductor efficiency, packaging, or radiation-to-charge conversion. Instead, these proposed research projects explore non-traditional architectures, hybrid systems, and novel carbon-based radioactive materials that could fundamentally reshape long-lived micro-power sources. Each concept targets a different mechanism—mechanical flexibility, hybrid trickle-charging, isotope-embedded semiconductors, and exotic carbon phases—illustrating how unconventional material science can unlock performance regimes unattainable with standard betavoltaics.

A first research direction develops flexible betavoltaic batteries, creating thin, bendable power sources suitable for wearables, remote IoT devices, and harsh-environment sensing. This project focuses on fabricating polymer–semiconductor substrates capable of integrating low-energy beta emitters such as C-14 or Ni-63. Key goals include optimizing microstructured converters for higher current output, improving encapsulation for radiological safety, and validating long-term reliability under repeated flexing. This approach aims to achieve decades of maintenance-free power delivery in formats that are impossible with rigid geometries. The key milestone of this research thrust is a flexible isotope power system platform that is bendable in response to stress without degration of the system.

A second project examines hybrid betavoltaic–chemical systems, where the betavoltaic cell continuously trickle-charges a conventional rechargeable battery. Such architectures leverage the constant but low current of beta decay to reduce deep discharge cycles, extend overall battery life, and minimize maintenance. Integrating β-sources into electrodes—such as in emerging Zn-ion hybrid concepts—demonstrates how long-lived radioisotope power can complement high-power chemical cells. This work emphasizes electrochemical integration, power-conditioning design, and lifetime modeling to assess the viability of hybrid long-duration power supplies. The key milestone of this research thrust is an integrated isotope power system and a conventional battery, where the isotope power system charges the conventional battery faster than the conventional battery's natural self-discharge.

A third project investigates C-14 synthetic diamond doped with tritium, using the diamond lattice as both a semiconductor and a physical host that safely traps tritium atoms. The hybrid material combines the structural stability and radiological containment of C-14 diamond with the higher beta output of tritium decay. The result could be a compact, intrinsically safe betavoltaic source capable of delivering ultra-low but persistent electrical power for medical implants or long-duration sensors. Research tasks include isotope incorporation, lattice-defect engineering, device fabrication, and radiological reliability testing. The key milestone of this research thrust is producing a diamond-encased tritium used in a system that delivers power.

A fourth research direction explores q-carbon made from C-14 as a next-generation betavoltaic material. Q-carbon’s unique properties—high sp³ content, extreme hardness, and strong diamond-nucleation behavior—may enable novel semiconductor junctions or improved beta-electron transport. The project includes synthesizing radiocarbon-based q-carbon via laser-induced transformations or PECVD, stabilizing it into diamond-like phases, and characterizing its electronic and radiative response. This unconventional material platform could lead to new betavoltaic architectures with enhanced conversion efficiency and tunable electronic properties, potentially surpassing the capabilities of standard diamond-based devices. The key milestone of this research thrust would be producing Q-carbon enriched with C-14 as a proof-of-concept.

Sources:

https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=studentship-2243804

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352152X25028051

¶ 10. Key Publications, Presentations and Patents

The patents and paper below were chosen based on what was determined as “key” from perspective to the Team. Each entry contains a description, relevancy, citation, and method section. Two patents and one paper were chosen to provide a balance of industrial and academic perspectives. The following paragraph summarizes the various techniques used to get to the three key documents.

To conduct the search, the search engines from various websites were used including the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), Google, Google Scholar, Google Patents, Web of Science, and others. Furthermore, various search terms were used such as “nuclear battery,” “alphavoltaic”, “remote power systems”, etc.” Search functions from the various databases were variable. Database filters and sorting mechanisms were used. Filters used included “highly cited papers;” sorting methods used include sort by date or number of citations. User evaluation was needed to determine if the patent or paper was considered key. For example, news or press articles and documents showing minor technological improvements were eliminated. Instead, documents that advanced the commercial viability of nuclear batteries was a key parameter to be selected.

¶ 10.1 Publications & Presentations

Recent Progress and Perspective on Batteries Made from Nuclear Waste

Description: The paper reviews the innovative use of nuclear waste materials for energy storage applications, specifically focusing on battery technologies. It highlights advancements in utilizing radioactive isotopes and other nuclear byproducts to create energy-dense, long-lasting batteries. The paper discusses various strategies for improving battery performance, safety, and waste management, addressing both technical and environmental challenges. It also explores the potential for these batteries to provide sustainable power for remote or long-term applications, such as space missions and medical devices, while minimizing the risks and costs of nuclear waste disposal.

Relevancy: This paper is highly relevant as it offers a sustainable solution to the growing problem of nuclear waste management. By turning waste into functional energy storage devices, it provides a dual benefit of reducing waste and creating long-lasting power sources. This innovation could revolutionize energy storage, especially for extreme environments and critical applications.

Citation: Katiyar, N.K., Goel, S. Recent progress and perspective on batteries made from nuclear waste. NUCL SCI TECH 34, 33 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01189-0

Method: Google Scholar was used with the search terms “nuclear battery waste.” The initial thought was to look into the state of end of lifecycle considerations of these devices. However, what made this article key was the consideration of where isotopes were sourced as well as its disposal. This paper was also chosen because it predates some more technical paper such as a battery developed by The Ohio State University and a patent from the United Kingdom.

¶ 10.2 Patents

A structured search was performed using the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) database and Google Patents, beginning with the keywords “radioisotope thermoelectric generator” and “thermoelectric material RTG.”

The search results were refined using Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) codes to identify the most relevant categories:

G21H 1/10 — Cells in which the radiation heats a thermoelectric junction.

G21H 1/103 — Cells provided with thermoelectric generators.

H10N 10/00 — Thermoelectric devices based on the Seebeck or Peltier effect.

These CPC categories encompass RPS that use nuclear decay to generate heat and convert it into electricity via thermoelectric couples—the same fundamental mechanism modeled in this project’s roadmap.

1. US 5,769,943 — “Thermoelectric Materials with Skutterudite Structure for Thermoelectric Devices.”

Fleurial, J.-P., et al. (1998). CPC H10N 10/00.

This foundational patent from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory discloses high-ZT skutterudite thermoelectric materials designed for enhanced efficiency in power-generation systems. The material family described here was later matured for NASA’s Enhanced Multi-Mission RTG (eMMRTG). It directly supports the roadmap’s focus on improving converter performance and energy density.

Source: Google Patents; NASA Technical Reports Server.

2. US 11,705,251 B2 — “Fuel Design and Shielding Design for Radioisotope Power Systems.”

(2023). CPC G21H 1/10, G21H 1/103.

This recent patent presents optimized fuel pellet geometries and shielding configurations that improve safety, thermal management, and integration within compact RPS architectures. Its innovations align with the roadmap’s subsystem considerations for fuel containment, mass optimization, and radiation safety in terrestrial RTG applications.

Source: Google Patents.

3. WO 2016/138389 A1 — “Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator.”

(2016). CPC G21H 1/10.

This international patent describes a miniaturized RTG design emphasizing compact geometry, hot- and cold-side thermal management, and efficient insulation for small-form-factor systems. It is relevant to emerging concepts of scalable, modular RTGs suitable for micro-power applications.

Source: Google Patents.

Historical Context

4. US 3,989,546 — “Thermoelectric Generator with Hinged Assembly for Fins.”

(1976). IPC G21H 1/10.

An early U.S. patent that illustrates classical RTG finned radiators for waste-heat rejection. Included here to show the historical evolution of thermal-management strategies in RTG packaging.

Source: International Nuclear Information System (INIS).

Emerging Radiovoltaic and Flexible Nuclear Batteries

In addition to thermoelectric-based RTGs, recent advancements in radiovoltaic (betavoltaic) technologies demonstrate alternative pathways for long-duration nuclear power generation. These systems convert charged particle emissions from beta decay directly into electricity via semiconductor junctions, eliminating the intermediate thermal stage. The following patents illustrate emerging directions in manufacturability and flexible design for next-generation nuclear batteries.

Method: To find these patents, the search terms “betavoltaic” and “flexible” were used on the USPTO’s basic search engine. The patent was chosen because flexibility expands the range of applications that this technology can consider.

5. US 10,706,983 B2 — “Mass Production Method of Loading Radioisotopes into Radiovoltaics.”

Kwon, Jae Wan; Gahl, John Michel; and Nullmeyer, Bradley Ryan. Issued July 14, 2020. Application No. 15/302,628; Filed April 11, 2014. CPC G21H 1/02.

This patent discloses a scalable, automated process for embedding radioisotopes into semiconductor-based radiovoltaic devices. The method uses precision alignment and controlled isotope deposition to achieve uniform energy distribution across large substrate areas while minimizing operator exposure and material loss. The design supports mass production of long-life nuclear batteries with consistent output and improved safety.

Relevance: This invention advances the manufacturability of radioisotope power sources, bridging the gap between laboratory prototypes and industrial-scale production. It contributes to the roadmap’s discussion on scalability, reliability, and cost reduction for compact, maintenance-free nuclear energy systems suitable for space, defense, and medical applications.

Source: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office; Google Patents.

6. US 12,347,580 B2 — “Nuclear Battery Including Flexible Nuclear Battery Module.”

Chen, Po-Lin; and Kuo, Chih-Tsung. Issued July 1, 2025. Application No. 18/341,457; Filed June 26, 2023. CPC G21H 1/02.

This patent introduces a flexible nuclear-battery architecture composed of multiple thin radiovoltaic modules embedded in bendable, layered substrates. The configuration allows the device to conform to curved or dynamic surfaces while maintaining energy conversion efficiency and structural integrity. Its multilayer semiconductor structure improves power density and mechanical durability relative to traditional rigid betavoltaic cells.

Relevance: This invention expands the functional domain of nuclear batteries into wearable, conformal, and flexible systems, offering persistent micro-power for long-duration or inaccessible environments. It complements the RPS patents by illustrating a parallel technological trajectory—one emphasizing form factor adaptability and solid-state reliability over heat-based conversion.

Source: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office; Google Patents.

¶ 11. Technology Strategy Statement

Our betavoltaic strategy advances long-life micro-power systems by utilizing novel materials, hybrid architectures, and manufacturable designs. Priorities include improving beta-electron capture using C-14 diamond, q-carbon, and flexible substrates; integrating hybrid betavoltaic–chemical trickle-charging; and strengthening safety and regulatory pathways. This approach targets critical sensors and extreme-environment electronics where decades-long, maintenance-free power outperforms conventional batteries.

We will explore the use of betavoltaic power sources for low-power IoT devices by 2030, with a focus on long-life sensors and infrastructure nodes. By 2035, we will expand into wearable electronics, including medical, fitness, and entertainment applications, where flexibility and durability are critical. By 2040, we aim to promote the adoption of ultra-long-lasting, maintenance-free consumer devices in the portable electronics sector.

(incl. “swoosh” chart)

¶ 12. Roadmap Maturity Assessment (optional)

¶ 13. References

“Figure 10 | On the Tuning of Electrical and Thermal Transport in Thermoelectrics: An Integrated Theory-Experiment Perspective.” npj Computational Materials, Nature, www.nature.com/articles/npjcompumats201515/figures/10.

Gayner, Chhatrasal and Kar, Kamal. “Recent advances in thermoelectric materials” Progress in Materials Science, vol. 83, 2016, pp. 380–382. ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0079642516300317.

“Plutonium Powered Pacemaker (1974).” Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity, ORAU, www.orau.org/health-physics-museum/collection/miscellaneous/pacemaker.html.

Madhusoodanan, Jyoti. “Inner Workings: Self-powered biomedical devices tap into the body’s movements.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 116, no. 36, 2019, pp. 17605–17607. PubMed Central (PMC), pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6731626/.

“Radioactive Wallet Cards Search.” National Nuclear Data Center, Brookhaven National Laboratory, https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/walletcards/radioactive.html.

Blanchard, James. “The Unlikely Revival of Nuclear Batteries.” IEEE Spectrum, 25 Aug. 2025, https://spectrum.ieee.org/nuclear-battery-revival.

“HD.17.071 (11966200113).” Atomic battery, Wikiwand, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HD.17.071_(11966200113).jpg. Accessed 4 Oct. 2025.

Narayan, Jagdish, et al. “Q-carbon Harder than Diamond.” MRS Communications, vol. 8, no. 2, June 2018, pp. 428-436. Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1557/mrc.2018.35.