¶ Pulsed Field-Reversed Configuration (FRC) Plasmoid Accelerator

Technology roadmap identifier within the Nuclear Fusion technology:

- 3PFPA - Pulsed Field-Reversed Configuration Plasmoid Accelerator (hyperlinked trailer)

¶ 1. Roadmap Overview

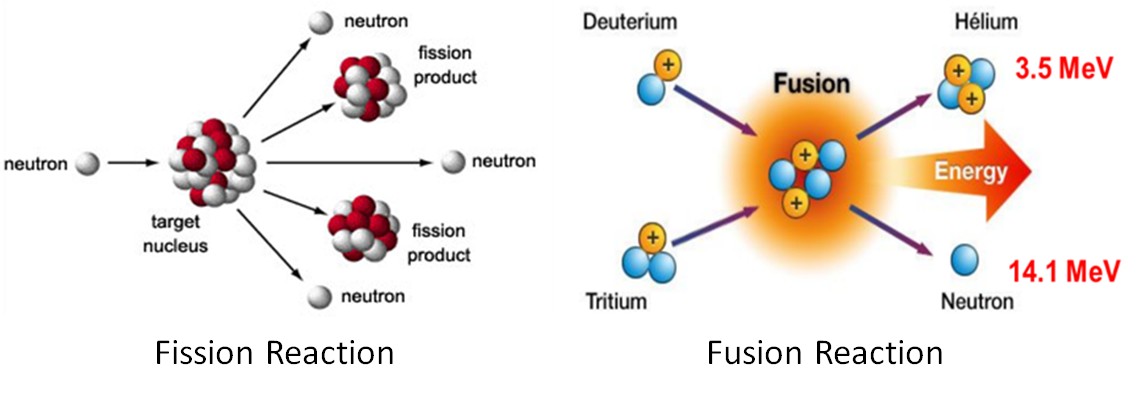

Nuclear energy is a highly attractive energy source due to the high energy density of the fuels in comparison to fossil fuels and renewable energy sources. Nuclear energy is released via fission reactions in which unstable nuclei split to release energy or fusion reactions in which isotopes are combined to form new particles while releasing energy equivalent to the mass difference between the reactants and products.

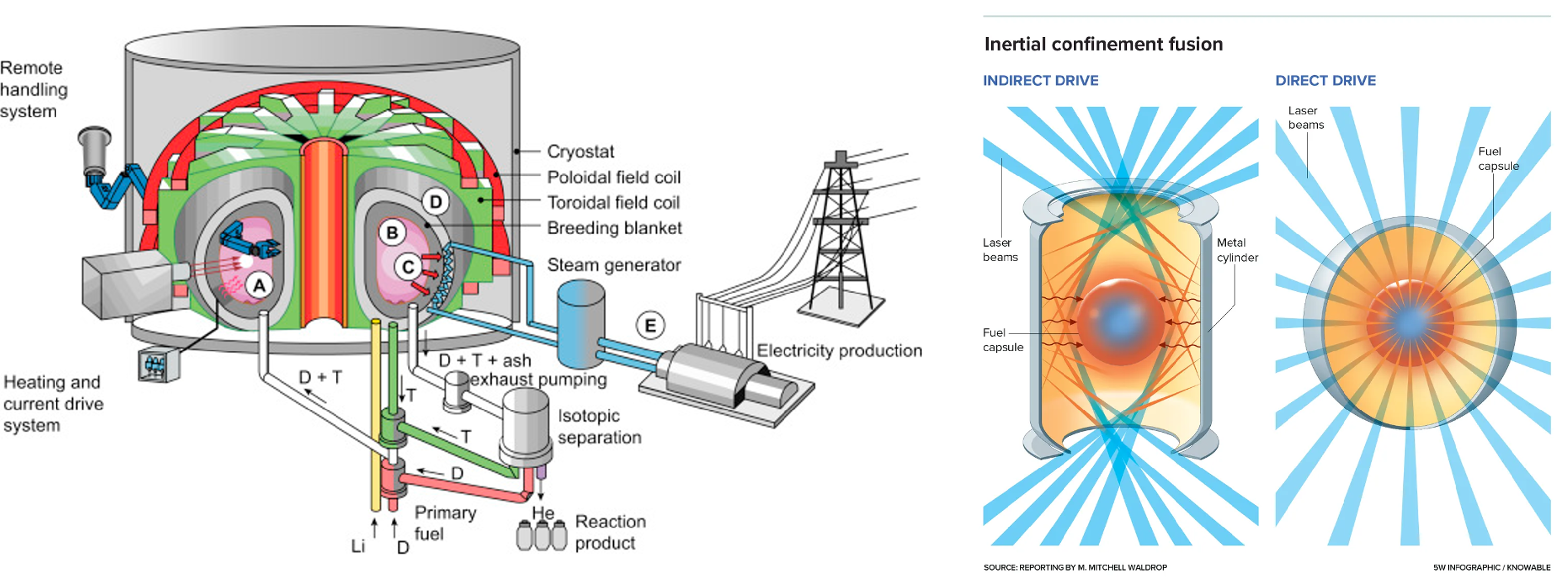

Fusion energy is an area of technology that is rapidly advancing and seeks to capture the energy generated by fusion reactions to produce usable electricity. The viability of fusion energy is highly dependent on how efficiently fuel can be burned and how long the reaction can be sustained. There are a variety of different approaches to achieving and sustaining fusion reactions including Magnetic Confinement Fusion (MCF), Inertial Confinement Fusion (ICF), and the hybrid Magneto-Inertial Fusion (MIF) approach.

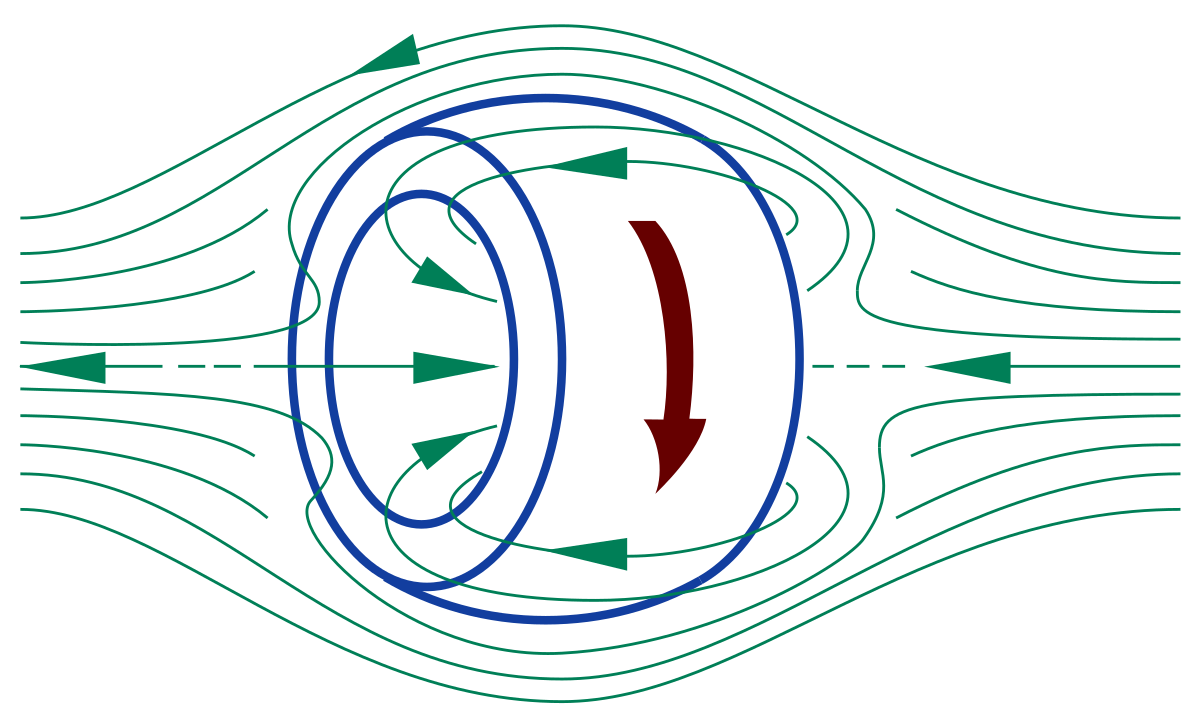

MIF represents a hybrid medium-density, medium-confinement-time approach to nuclear fusion. It seeks to combine elements of the traditional fusion techniques (MCF & ICF) to overcome the limitations that hinder each. This hybrid approach is generally characterized by the use of magnetic fields to pre-confine plasma, followed by a rapid compression technique to reach fusion conditions.

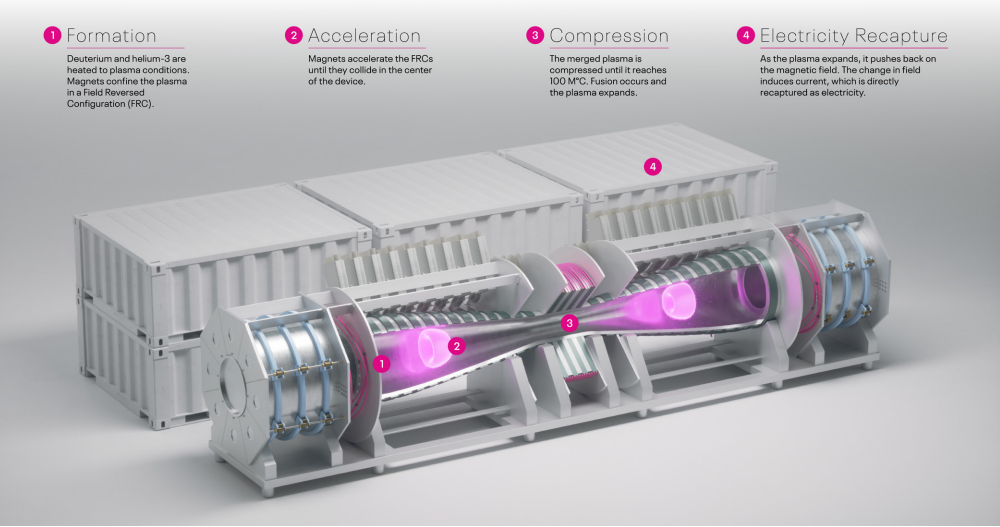

The MIF method analyzed in this roadmap confines two plasmas in a Field-Reversed Configuration (FRC) and merges them at high speed to reach sufficient fusion reaction conditions. This process is then repeated rapidly to achieve a high energy delivery rate to compete with existing commercial electricity production.

Helion Energy based in Everett, Washington is the primary company pursuing Pulsed FRC Plasmoid Accelerator (PFPA) based fusion as of November 2025. The Helion reactor design utilizes a Deuterium & Helium-3 fuel source. The resultant fusion reaction is predominantly composed of charged particles, allowing Helion to employ efficient direct energy recapture techniques. Helion's MIF approach notably does not attempt to reach sustained ignition but instead explores the efficiency and viability of pulsed-driven fusion reactors.

The diagram below illustrates Helion Energy's approach to MIF:

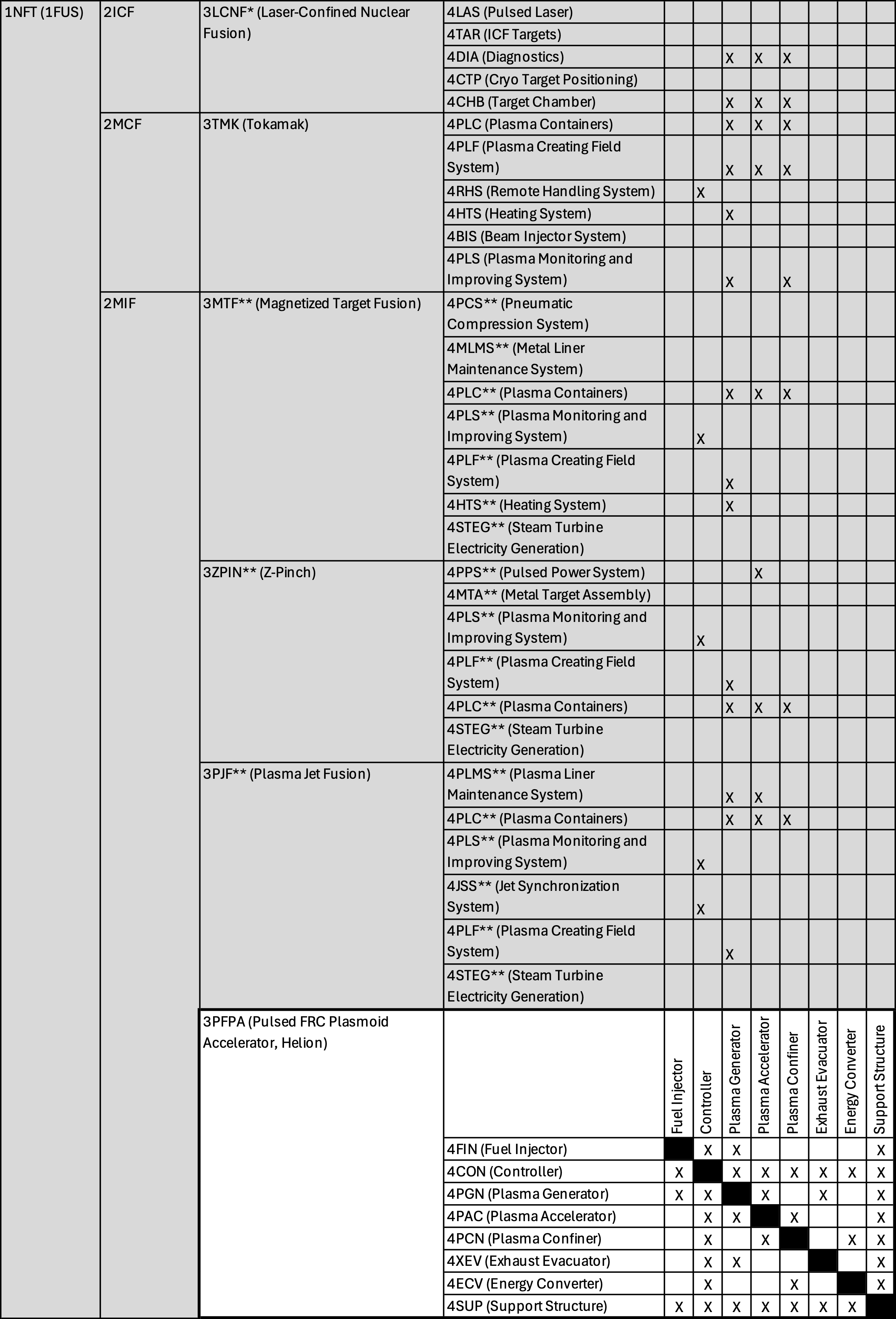

¶ 2. Design Structure Matrix (DSM) Allocation

The 3PFPA roadmap has a direct connection to the 1NCF & 2LCNF roadmaps, as shown in the figure below. Despite being highly connected to these roadmaps, the 1NCF & 2LCNF roadmaps demonstrate inconsistencies with one another that should be resolved to create an internally consistent portfolio of fusion technology roadmaps. This roadmap proposes changing 2LCNF to level 3 (3LCNF) and adding a level 2 roadmap for Inertial Confinement Fusion (2ICF). Additionally, the 1NCF roadmap structure needs to add an intermediary level 3 to be consistent with the other fusion approaches (3TMK for Tokamak approaches of MCF).

Under this top-level structure, MIF creates a third branch in level 2 (2MIF) with the Pulsed FRC Plasmoid Accelerator being a specific method of MIF (3PFPA). The DSM for 3PFPA has strong associations with the plasma-related aspects of both the 3LCNF and 3TMK roadmaps, including plasma diagnostics and plasma confinement technologies. Control systems are also an intrinsic and shared aspect of all fusion technology roadmaps.

There are missing associations between the other roadmaps for features that should be shared, such as fuel management and reactor support structures, which are present in 3PFPA but unaddressed in the other roadmaps. This indicates a need to reconcile the system boundary for the technology for this and the other fusion roadmaps.

Overall, there is substantial overlap in the DSMs for all technologies within the 1NCF branch; however, a major area of deviation between 3PFPA and the other roadmaps is the energy conversion methodology, which involves capturing electricity through current induction, as opposed to the use of steam turbines that utilize the heat from neutron interactions with reactor blankets.

(* recommended modification of existing roadmap, ** proposed roadmaps for future work)

¶ 3. Roadmap Model using OPM

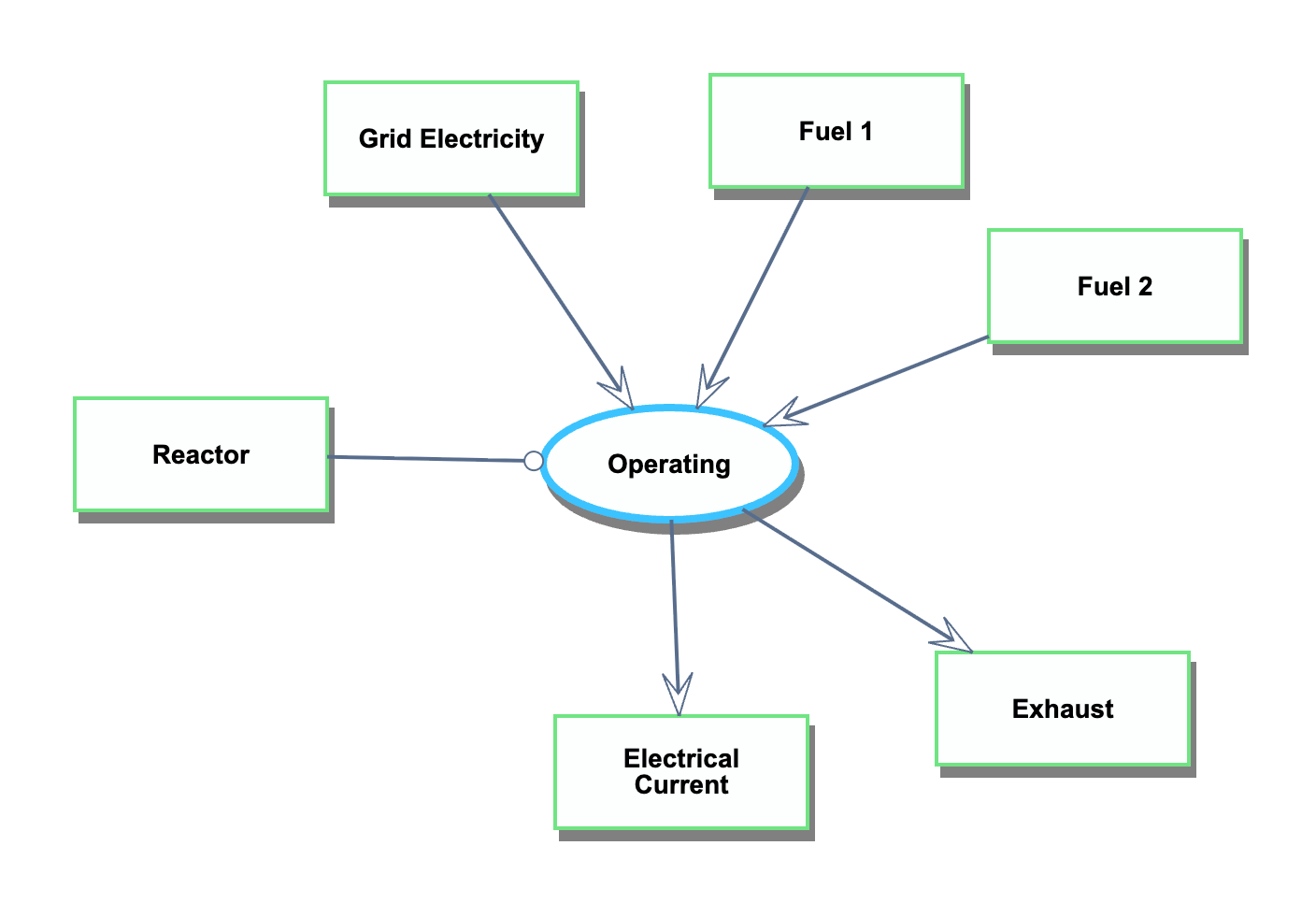

¶ 3.1 Top-Level OPD & OPL

A Level 3 Object-Process Diagram (OPD) for 3PFPA is shown below. The top-level process and object for this OPD is an operating reactor that utilizes fuel and grid electricity to generate electricity. Energy storage is outside the system boundary for this OPD.

¶ Object Process Diagram

¶ Object Process Language

Fuel 1 is a physical and systemic object.

Grid Electricity is a physical and systemic object.

Electrical Current is a physical and systemic object.

Reactor is a physical and systemic object.

Exhaust is a physical and systemic object.

Fuel 2 is a physical and systemic object.

Operating is a physical and systemic process.

Operating requires Reactor.

Operating consumes Fuel 1,Fuel 2, and Grid Electricity.

Operating yields Electrical Current and Exhaust.

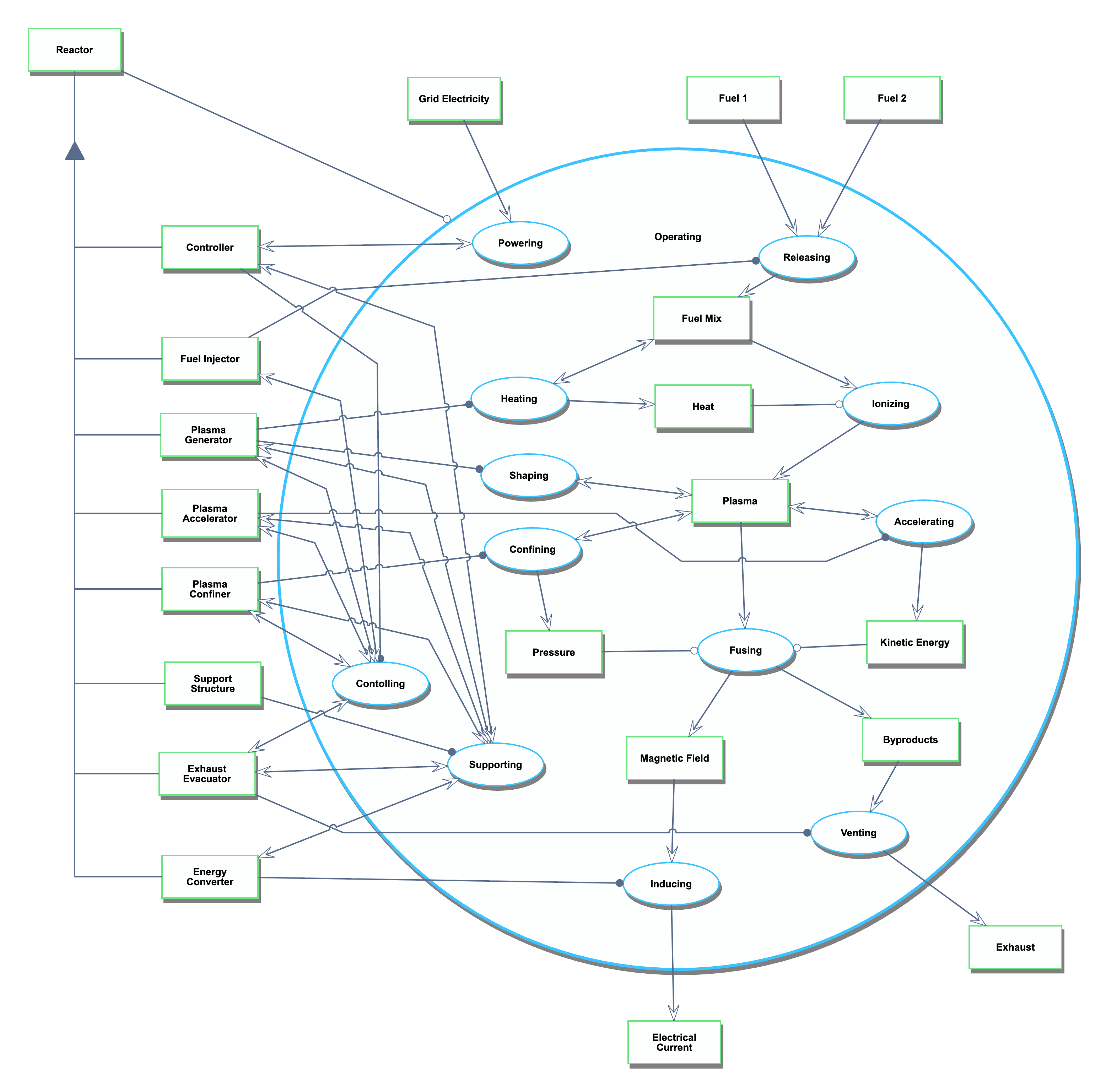

¶ 3.2 Detailed OPD & OPL

The detailed/zoomed-in OPD for the reactor provides greater insight for how the PFPA combines both MCF and ICF methods since there is the traditional plasma confinement from MCF and the plasma acceleration from ICF which both act on the plasma to reach fusion conditions.

Additionally, the unique method of energy recovery is reflected in this OPD since electricity is directly captured via magnetic field induction of the fusing plasma. For traditional steam turbine approaches, this portion of the OPD would be far more complex with heat production, heat exchange, and turbine rotation needing to be added, thus making the OPD a useful illustration of one of the competitive advantages for this technology.

¶ Object Process Diagram

¶ Object Process Language

Operating from SD zooms in SD1 into Powering,Releasing,Heating,Ionizing,Shaping,Accelerating,Confining,Fusing,Contolling,Supporting,Venting, and Inducing, which occur in that time sequence, as well as Byproducts,Fuel Mix,Heat,Kinetic Energy,Magnetic Field,Plasma, and Pressure.

Fuel 1 is a physical and systemic object.

Grid Electricity is a physical and systemic object.

Reactor is a physical and systemic object.

Electrical Current is a physical and systemic object.

Exhaust is a physical and systemic object.

Plasma Accelerator is a physical and systemic object.

Energy Converter is a physical and systemic object.

Plasma Confiner is a physical and systemic object.

Exhaust Evacuator is a physical and systemic object.

Fuel Injector is a physical and systemic object.

Controller is a physical and systemic object.

Plasma Generator is a physical and systemic object.

Support Structure is a physical and systemic object.

Fuel 2 is a physical and systemic object.

Plasma is a physical and systemic object.

Pressure is a physical and systemic object.

Kinetic Energy is a physical and systemic object.

Byproducts is a physical and systemic object.

Magnetic Field is a physical and systemic object.

Fuel Mix is a physical and systemic object.

Heat is a physical and systemic object.

Reactor consists of Controller,Energy Converter,Exhaust Evacuator,Fuel Injector,Plasma Accelerator,Plasma Confiner,Plasma Generator, and Support Structure.

Operating is a physical and systemic process.

Operating requires Reactor.

Fusing is a physical and systemic process.

Fusing requires Kinetic Energy and Pressure.

Fusing consumes Plasma.

Fusing yields Byproducts and Magnetic Field.

Confining is a physical and systemic process.

Plasma Confiner handles Confining.

Confining affects Plasma.

Confining yields Pressure.

Accelerating is a physical and systemic process.

Plasma Accelerator handles Accelerating.

Accelerating affects Plasma.

Accelerating yields Kinetic Energy.

Heating is a physical and systemic process.

Plasma Generator handles Heating.

Heating affects Fuel Mix.

Heating yields Heat.

Shaping is a physical and systemic process.

Plasma Generator handles Shaping.

Shaping affects Plasma.

Venting is a physical and systemic process.

Exhaust Evacuator handles Venting.

Venting consumes Byproducts.

Venting yields Exhaust.

Inducing is a physical and systemic process.

Energy Converter handles Inducing.

Inducing consumes Magnetic Field.

Inducing yields Electrical Current.

Powering is a physical and systemic process.

Powering affects Controller.

Powering consumes Grid Electricity.

Contolling is a physical and systemic process.

Controller handles Contolling.

Contolling affects Exhaust Evacuator,Fuel Injector,Plasma Accelerator,Plasma Confiner, and Plasma Generator.

Releasing is a physical and systemic process.

Fuel Injector handles Releasing.

Releasing consumes Fuel 1 and Fuel 2.

Releasing yields Fuel Mix.

Ionizing is a physical and systemic process.

Ionizing requires Heat.

Ionizing consumes Fuel Mix.

Ionizing yields Plasma.

Supporting is a physical and systemic process.

Support Structure handles Supporting.

Supporting affects Controller,Energy Converter,Exhaust Evacuator,Plasma Accelerator,Plasma Confiner, and Plasma Generator.

¶ 4. Figures of Merit (FoM)

There are many FoM associated with nuclear fusion energy including many pertinent to energy production as a whole. Below, seven common FoM are detailed, covering three main categories:

| Category | Name | Unit | Short Description | Goal |

| Performance | Energy Gain (Q) | Unitless | Ratio of the output energy of the reactor to the input energy of the reactor | Maximize |

| Triple Product | keV·s·m⁻³ | Intensity of fusion conditions within the reactor's plasma | Achieve Threshold Value | |

| Individual Pulse Energy | MJ | Output energy of a single operational cycle (pulse) of the reactor | Maximize | |

| Pulse Repetition Rate | Hz | Frequency that a reactor can be pulsed at during operation | Maximize | |

| Productivity | Energy Production Cost | $/kWh | Capital expenditure per unit of energy production with a focus on operations | Minimize |

| Capital Efficiency | $/MW | Capital expenditure required to achieve a given level of energy production with a focus on reactor production | Minimize | |

| Efficiency | Fuel Efficiency | Unitless | Efficiency with which fuel is converted into electricity | Maximize |

Energy Gain (Q) [-]: Energy gain is the primary metric for assessing the energy yield of fusion technologies. It is defined mathematically as the ratio of output energy to input energy and is therefore dimensionless. Energy gain Q can be evaluated at the reaction or system level. Ideally, MIF yields net positive energy production and has a Q > 1. This is physically possible while still adhering to Einstein's mass-energy equivalence formula (E=mc2) as the fusion processes release energy as atomic mass is lost during the reaction, balancing terms on both sides of the equation.

Q = Energy Output / Energy Input

Although Helion has not openly reported Q values at the reaction or subsystem level, a sign of a healthy and maturing technology is an increasing Q value over time.

Triple Product [keV·s·m⁻³]: Traditionally, the triple product provides insight into the maturity of the fusion reaction as it measures how close the reaction is to reaching self-sustaining fusion, commonly referred to as “ignition”. Although MIF is a non-igniting methodology, the triple product is still a useful FoM in order to measure maturity and compare it to other forms of fusion. When assessing MIF, this FoM must be considered in conjunction with others to understand the overall commercial feasibility and utility of MIF.

n⋅T⋅τ

n = plasma density [particles per m³]

T = plasma temperature [keV]

τ = energy confinement time [s]

Helion more openly publishes figures associated with density, temperature, and energy confinement times. These values are largely trending upwards with each generation of prototype reactor.

Individual Pulse Energy [MJ] & Pulse Repetition Rate [Hz]: Significant barriers to commercializing MIF fusion technology lie in the complexity surrounding scaling and evaluating its suitability for providing continuous energy to a potential grid. The reactor's individual pulse energy and its ability to reliably, continuously pulse are FoMs one can use to assess the commercial viability of the MIF fusion solution. This is comparable to the challenges currently faced by ICF approaches, such as those at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory's National Ignition Facility.

Helion has not openly reported Individual Pulse Energy but has shared limited data points on the Pulse Repetition Rates. Helion achieved a 0.0017 Hz (once every ten minutes) with their Trenta 6th-generation prototype and has shared that Polaris (7th-generation prototype) is targeting a 1 Hz pulse repetition rate.

Energy Production Cost [$/kWh]: Like reactor individual pulse energy and pulse repetition rate, the cost to produce electricity is a figure of merit that allows one to assess the viability of the technology in the context of not only fusion technologies, but also traditional energy production technologies.

Helion has not formally sold fusion energy to customers. On July 30, 2025, Helion announced that it had begun construction on Orion, its first fusion power plant, which is expected to provide 50 MW of fusion-derived electricity to Microsoft's data centers starting in 2028. Helion’s long-term goal is to produce electricity at $0.01/kWh.

Capital Efficiency [$/MW]: The energy sector typically uses capital efficiency to evaluate and compare the financial feasibility of various energy sources. A lower value implies higher efficiency. Once proven with MIF, this metric can be used to assess fusion power solutions against common primary energy sources, such as solar, wind, coal, and natural gas.

CAPEX/MW = Total Capital Expenditure / Total Capacity in MW

Fuel Efficiency [-]: For any power-generating reactor, it is important to assess how efficiently the relevant energy (e.g., latent heat, mass defect, etc.) is converted into electricity.

𝜂fuel=𝐸𝑙𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝐺𝑒𝑛𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑 [𝑘𝐽] / 𝐸𝑛𝑒𝑟𝑔𝑦 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝐹𝑢𝑒𝑙 [𝑘𝐽]

¶ 5. Alignment of Strategic Drivers: FoM Target

The current pioneer for the 3PFPA technology and thus most relevant to this roadmap is Helion Energy, based in Everett, Washington. Helion is a private company focused on the commercialization of fusion energy and is currently in the development phase for its reactor technology. Since Helion's primary goal is to commercialize fusion technology and one day sell energy to the grid, the company is likely following FoMs in alignment with their strategic drivers:

| Number | Category | Strategic Driver | Alignment and Targets |

| 1 | Business | To deliver electricity produced by fusion reactions at a commercial scale with competitive pricing | The 3PFPA Technology Roadmap will target an energy sales cost of $0.01/kWh and this driver is aligned with 3PFPA. |

| 2 | Business | To capture a large clean-energy market share | The 3PFPA Technology Roadmap will target an operational date of 2028 for its Orion reactor that is commissioned for Microsoft and 2030 for its reactor commissioned for Nucor. This driver is aligned with 3PFPA. |

| 3 | Product | To demonstrate a novel energy capture method | The 3PFPA Technology Roadmap will target an energy recovery of 95% of the charged particle energy from the reaction. This driver is aligned with 3PFPA. |

| 4 | Product | To develop a commercial-scale pulse-power array to support reactor operations | The 3PFPA Technology Roadmap will target a pulse rate of 10Hz and this driver is aligned with 3PFPA. |

| 5 | Product | To develop reactors that can operate on different fuel types | The 3PFPA Technology Roadmap is currently focused on only a D-He3 fuel source for operation. Compatibility with D-T fuel should be pursued since it is a more reactive fuel that will become more accessible. This includes designing for integration of neutron blankets and steam turbines. This driver is not aligned with 3PFPA currently. |

Helion's continued development efforts of its cornerstone technology and commitments to high-profile investors result in its strategic drivers being highly aligned with the 3PFPA roadmap. The degree of alignment is likely to decrease once a commercial system is developed, as the company diversifies its technology portfolio.

¶ 6. Positioning of Organization vs. Competition: FOM charts

Consumers of fusion-generated electricity have two primary needs: a low cost of energy and minimal emissions production. These needs are independent of the fusion technology used, meaning that it is necessary to assess all areas of fusion energy production (1NFT) to understand the positioning of Helion's FRC approach. Due to the absence of commercially operating fusion reactors in 2025, there is very limited data availability outside of research settings, prototypes, or simulated performance. To limit the impact of the ubiquitous uncertainty in the field, only the triple product and operational frequency rates were compared across the fusion approaches. The table below provides a brief overview of the fusion market in 2025, with an emphasis on MIF approaches, as these approaches are most closely tied to this roadmap.

| Category |

Name |

Developer |

Ion density n [m-3] |

Temperature T [keV] |

Confinement Time τE [s] |

Triple Product nTτE [keV*s/m3] |

Operational Frequency f [Hz] |

| MIF | Pulsed FRC Plasmoid Accelerator (PFPA)* | Helion Energy | 1x1022 | 8.5 | 1x10-3 | ~8.5x1019 | 1 |

| MIF | Magnetized Target Fusion (MTF) | General Fusion | 6x1019 | 0.4 | 1x10-2 | ~2.4x1017 | 0.1 |

| MIF | Magnetized Liner Inertial Fusion (MagLIF) | Sandia National Laboratory | 1x1021 | 2.5 | 1x10-6 | ~2.5x1015 | 0.001 |

| MIF | Plasma Liner Experiment (PLX) Plasma Jet* | Los Alamos National Laboratory | 1x1021 | 1.5 | 1x10-4 | ~1.5x1017 | 0.01 |

| MIF | Z-Pinch | Zap Energy | 1x1023 | 2 | 1x10-6 | ~2x1017 | 5 |

| MCF | SPARC* | Commonwealth Fusion Systems | 1x1020 | 15 | 5 | ~7.5x1021 | Continuous |

| MCF | Steady-state FRC | TAE | 5x1019 | 3 | 3x10-2 | ~4.5x1018 | Continuous |

| ICF | National Ignition Facility (NIF) | Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory | 1x1031 | 7.5 | 1x10-9 | ~7.5x1022 | 10-4 |

| ICF | Arc Reactor* | Marvel Fusion | 1x1026 | 300 | 1x10-12 | ~3x1016 | 10 |

| *Simulated, designed, or projected values | |||||||

When comparing the MIF approaches, it is evident that Helion Energy's (projected) performance is highly competitive and would be dominant compared to other MIF options. It is worth noting that the Sandia National Laboratory (SNL) Magnetized Liner Inertial Fusion (MagLIF) approach and the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) PLX approach are both research-focused systems, so comparisons to these options may not be meaningful.

The substantial amount of leading design options that are projections highlights that this roadmap requires regular updating over the next decade to document alignment of actual performance with projections. The progression of the Pareto front for the triple product and the relative location of the Helion FRC approach (yellow star labeled FRC) are shown below. It is evident that, despite the competitive advantage relative to other MIF approaches, the triple product is still dominated by tokamaks (SPARC for Commonwealth in the upper right) and NIF (cluster of X's to the lower left of SPARC & ITER). With a low operational frequency and research focus, NIF is not a competitive reactor option, but SPARC's higher triple product and relatively continuous operation make it a highly competitive, if not dominant, reactor technology relative to Helion's FRC.

Helion is projecting advancements in magnetic field capabilities that will increase temperature and triple product. These values are currently ill-defined and unverified, but warrant close monitoring to see if the gap can close between current tokamaks and the PFPA. The progress in the magnetic field for various generations of Helion's reactors is shown below along with the corresponding plasma temperature for the Grande and Trenta reactors (temperatures for the other reactors were not reported). There has been steady progression and correlation between the magnetic field and temperature (16% growth annually and 11% growth annually) which could aid in PFPA matching the performance of tokamaks if the growth can be maintained as shown in the forecast. The forecast extends until the ideal triple product temperature for a D-He3 fuel reaction is reached (58keV).

Another potential competitive advantage that should be addressed by future iterations of this roadmap is fuel costs. The fuel supply chain for all fusion reactors is currently not well developed, so any competitive advantage for fuel is likely to be highly volatile.

¶ 7. Technical Model: Morphological Matrix and Tradespace

¶ Morphological Matrix

Modeling the dynamics of a fusion reaction and by extension a fusion reactor is a nontrivial matter given the complex atomic interactions occurring, the highly dynamic environment, and the real-world nonidealities that are highly application specific. A comprehensive technical model is thus infeasible for the scope of this roadmap; however, a simplified model can be generated specifically for the fusion reaction (the heating, shaping, confining, accelerating, fusing, and ionizing process from the OPM) that has connections to reactor design choices. The main choices relevant to the reaction itself from the morphological matrix below include the Fuel Type, Inertia Method, Plasma Type, Heating Method, and Magnetic Method.

¶ Model:

The selection of options for these decisions will determine various inputs to the model that are outlined below:

Due to the complexity and uncertainty associated with many of these values, a handful of variables with higher certainty were selected to assess the sensitivity of the reactor's performance to key design variables which include: the reactor chamber volume (Vchamber), the reactor chamber pressure (Pchamber), the initial temperature (Tinitial), the magnetic field strength (B), and the preheated plasma temperature (Tpreheat). With the focus of this model on the fusion reaction itself, the most relevant FOMs are the fuel efficiency (𝜂fuel) and the energy production per cycle (Ecycle), but there are many useful intermediate FOMs that were analyzed during model creation including the latent fuel energy per cycle (Efuel), and final plasma temperature (Tplasma,final) which have direct impact on the fuel efficiency and energy production. Key assumptions made for the model include application of the ideal gas law, complete fuel burn per cycle, all energy is capturable, and ideal reaction between fuels (i.e. all reactions that occur are the intended fuel reaction and are not other possible reactions such as D-D in a D-He3 reactor). The latter assumption will result in the D-He3 configurations overperforming in lower temperature ranges (below 50 keV).

The ultimate constraint on the output energy of a fusion reaction cycle is the amount of fuel that is involved in a given reaction cycle (hence its consideration as an FOM). This corresponds to the latent fusion energy within the fuel (varies with fuel/reaction type) and the reactor chamber characteristics, since the combination of these two will determine what the maximum amount of fuel in a cycle can be and thus the maximum number of possible reactions. Fusion reactions also vary in their outputs, with energy being carried either by neutrons or charged particles, a major factor influencing the selection of capture methods. Given that all energy is considered capturable (neutron/charged particle agnostic), this model will include all energy forms in the calculation of the fuel energy per cycle (see below).

The distinctive feature of MIF technology is the utilization of both magnetic methods and inertial methods to produce confinement pressures that lead to fusion conditions. In this model, this feature is represented by the final plasma pressure, which is equivalent to the compression pressure applied to the plasma. The compression pressure is the sum of the ram pressure, generated by the kinetic energy imparted on the plasma by the acceleration medium/method, and the magnetic pressure from the Lorentz force. The expression for the final plasma pressure is given below:

Utilizing the ideal gas law and compression pressure, expressions for the final pressure, temperature, and volume characteristics of the plasma can be derived and substituted into other reaction-relevant expressions, such as the reactivity of the fuel. The reactivity of nuclear fusion fuels is highly dependent on the final temperature of the plasma and the type of fuel. The previous pressure expression can be converted using the ideal gas law to solve for the final temperature of the plasma (Tplasma, final) and then substituted into the Hively reactivity approximation.

Hively reactivity approximation:

Each fuel type has its own constants for this approximation, and notably, the D-D combination has two possible reactions that can occur: one generates a proton and tritium (D-D1), and another generates a neutron and Helium-3 (D-D2). This difference results in two separate sets of calculations for the remaining FOMs, accounting for the multiple reactivity values and the identical reactants, which halve the ion densities used. With the chamber properties, fuel energy, and reactivity known, it is possible to calculate the power generated by the reaction.

With the power expression defined, the top-level FOM of energy per cycle (Ecycle, also referenced as Epulse) can be calculated by summing the power generated over the confinement time (τE). This is a very simplistic approach, as it assumes that power generation remains constant over the confinement time. Future models should assess the temporal variation of power generation.

Following the calculation of energy per cycle, the fuel efficiency is straightforward to determine by comparing the cycle energy to the latent energy of the fuel.

¶ Sensitivity Analysis

To efficiently focus technological development efforts, it is paramount to understand the sensitivity of key FOMs to various design variables. For the model of the fusion reaction, the design variables most applicable to such an analysis include: the reactor chamber volume (Vchamber), the reactor chamber pressure (Pchamber), the initial temperature (Tinitial), the magnetic field strength (B), and the preheated plasma temperature (Tpreheat). Due to the complexity of the expressions for the top-level FOMs (Ecycle & 𝜂fuel), computational methods were utilized to perform finite difference approximations in MATLAB. The intermediate FOMs of (Efuel) and (Tplasma,final) are much more conducive to performing partial derivatives for the sensitivity analysis and are shown below:

Efuel Expression:

Efuel Partial Derivatives:

Tplasma,final Expression:

Tplasma,final Partial Derivatives:

The partial derivatives can be assessed using approximate input values (actual values are not published by virtually all fusion companies) and normalized to assess the sensitivity of the FOMs to these design variables. The tornado charts plot these normalized sensitivities and indicate that the preheated temperature of the plasma (Tpreheat) has the most impact on the FOM of interest while changes to the reactor's chamber volume (Vchamber) will have less impact on performance (outside of fuel energy).

.png)

¶ Tradespace:

This model is useful for preliminary explorations of how the reactor geometric design and input conditions can impact the potential performance of the MIF technology. Approximations for several existing MIF reactor configurations are assessed and compared in the tradespace below, focusing on the importance of reactor chamber volume (selected as the most readily accessible data point). The data was normalized to the approximate performance of Helion's FRC reactor. The tradespace highlights that the Sandia and LANL systems are designed for research purposes, given their relatively low performance compared to commercially oriented reactors. It is also important to reemphasize that these are approximations that require refinement based on actual data when/if available.

¶ 8. Financial Model: Technology Value (NPV)

Traditional primary energy sources, such as crude oil, natural gas, and coal, continue to dominate the global commercial energy landscape, despite the push over recent years to transition towards cleaner energy alternatives. In 2023, the U.S. alone consumed 93.59 quadrillion Btu of primary energy, ~83% of which was derived from fossil fuels, and annual energy demand continues to increase (U.S. Energy Information Administration [EIA], 2024). It is estimated that energy requirements in the data and EV sectors alone will grow by 20% over the next 25 years (Walsh, 2024). Nuclear fusion technology has the potential to revolutionize the global energy landscape by providing abundant, nearly carbon-free energy if it is commercialized and brought to market (U.S. Department of Energy, n.d.).

Because this roadmap addresses an enabling technology, the financial model characterizes Helion’s anticipated operational fleet over a 30-year timeframe, including both the Orion and Nucor facilities, to provide a forward-looking assessment of economic performance and financial risk. When possible, financial assumptions were drawn from the 2LCNF roadmap to ensure continuity. The primary assumptions used in the model are listed below:

| Assumption | Units | Orion | Nucor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advertised Capacity | MWe | 50 | 500 |

| Performance Uptime | % | 75 | 75 |

| Annual Energy Output | MWh/yr | 328,500 | 3,285,000 |

| Construction | yrs | 2 | 2 |

| Construction Start Year | yrs | 0 | 3 |

| Opperational Lifetime | yrs | 30 | 30 |

| Total CAPEX | $M | 150 | 500 |

| Fixed OPEX | $M/yr | 5 | 15 |

| Variable OPEX | $/MWh | 7 | 5 |

| Tax Rate | % | 20 | 20 |

| Discount Rate | % | 12 | 12 |

| LCOE (Calcuated) | $/MWh | 82.31 | 29.60 |

Orion begins construction in Years 1–2 and enters operation in Year 3 with limited positive cash flow driven by the reactor's relatively low CAPEX. This is a conservative CAPEX estimate, assuming return on investment savings from Helion's in-house manufacturing capabilities. Nucor begins construction in Years 4–5 and transitions to full operation in Year 6, at which point total fleet revenue increases by an order of magnitude due to 10× higher capacity of the Nucor reactor.

The NPV trajectory illustrates the long-term financial dynamics of fusion deployment. The model shows that early high-cost construction years generate significant negative cumulative NPV, but this trend reverses once industrial-scale energy generation begins. The break-even point occurs around Year 14, indicating that a two-plant fusion deployment can achieve positive economic value within the first half of the operating horizon under the assumed CAPEX, OPEX, availability, and PPA prices. The results emphasize two key insights:

1) Small demonstration systems like Orion allow Helion to be the first to market, but they alone cannot deliver attractive economics.

2) The addition of a large-scale industrial plant like the Nucor Reactor plant rapidly improves financial performance, highlighting the importance of scaling and fleet deployment for fusion to be commercially viable.

This model notably does not take into consideration any future tax credits. The Fusion Advanced Manufacturing Parity Act (H.R. 5441 / S. 3088), for example, was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives on September 17, 2025. If approved, this Act would provide a 25% manufacturing tax credit for domestically produced fusion energy components. This tax credit would reduce the construction burden of the Helion reactors and shift the break-even point to the left.

It is to be noted that the Python script used to model Helion's reactor fleet and generate the above NPV graph was derived from the analytical framework presented in Hawker’s “A simplified economic model for inertial fusion” (2020). The code was modified with the assistance of ChatGPT. Please see “References” for the full APA reference for both resources.

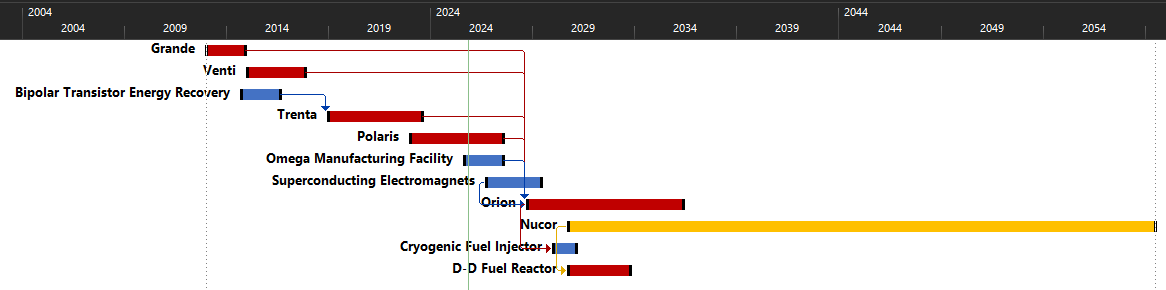

¶ 9. List of R&D Projects and Prototypes

Helion has chosen a rapid iterative prototype approach to developing and maturing thier fusion technology. Unlike others in the academic research and development fusion space that build prolific reactors that take many years and hundreds of millions of dollars to construct, Helion has focused on building scale models that incrementally advance key aspects of thier technology. Each prototype generation is engineered to de-risk, validate aspects of their design, and generate data for thier next generation design. This approach has ultimately allowed Helion to reduce development timelines, build confidence in thier technology, and showcase continuous incremental improvements to investors, ultimately leading them to power purchase agreements and collaborations with Microsoft and Nucor.

| Name | Generation | Description | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grande | 4th Generation Prototype | Demonstrated direct energy recapture methods. Achieved ~4T peak magnetic field & 5keV temperatures. | Retired (2012 - 2014) |

| Venti | 5th Generation Prototype | Demonstrated scaling field strength and pulse rates. Achieved ~7T peak magnetic field, and D-D fusion. | Retired (2015- 2018) |

| Trenta | 6th Generation Prototype | Achieved~8T peak magnetic field, ~9 keV temperatures, and 10,000+ fusion pulses over 2-year span. | Retired (2019- 2023) |

| Polaris | 7th Generation Prototype | Targets 15T+ peak magnetic field, net-positive electricity demonstration and compatible pulsed operations (1Hz repetition rate). | In Use* (2023 - Present) |

| Orion | Commercial Demonstrator Plant | First grid-connected fusion power plant, scaling Polaris architecture to ~ 50 MWe. Under construction for Microsoft under power purchase agreement (PPA). | Under Construction, Estimated Completion Date 2028 |

| Nucor | Commercial Industrial Plant | Scales Orion's architecutre to ~500 MWe (10x). Will be built for Nucor, the largest North American steel producer and recycler. | Construction Not Started, Estimated Completion Date 2030 |

Beyond the existing demonstrators Helion has pursued, there are additional R&D efforts that are necessary to pursue for the Microsoft and Nucor delivery targets to be achieved as indicated by the technical model and financial model. The technical model indicates that investments into increasing the preheated plasma temperature and reducing the initial fuel temperature are the most impactful changes that can be made for reactor fuel efficiency. Therefore, it is recommended for Helion to pursue superconducting electromagnets and cryogenic fuel injection R&T projects to see sizable gains in reactor performance. These projects also share a need for cryogenic cooling (undefined roadmap) meaning the overall effort across the two efforts will be lower compared to alternatives.

From the financial model, the substantial construction costs result in a long payoff period which can be offset by lowering the fabrication costs and/or reducing the operating costs of the reactors. Helion announced in September 2025 the intent to construct a dedicated fabrication facility named Omega that will handle the fabrication of critical and long-lead components such as the high-voltage capacitors needed for plasma acceleration. An in-house fabrication capability also has the additional benefit that iteration through the R&D cycle will be accelerated leading to reduced testing costs. Once the reactors have been constructed, the fuel costs are a substantial fraction of the operating expenses, so development of the D-D fuel reactor identified in Helion's patent US 11,469,003. With the aggressive targets set for operation, this development will occur concurrently with operation of the Nucor reactor.

¶ 10. Key Publications, Presentations and Patents

¶ 10.1 Publications & Presentations

The number of patents (pending or issued) implies that Helion is maturing and refining its approach to MIF. Because Helion is a for-profit entity with many patent-pending applications, there are few formal publications that detail the nuances of its work, although David Kirtley (CEO & Co-Founder Helion Energy) has published multiple papers on the overall concept of MIF. It is worth noting that Helion participates in conferences and events; however, the materials from these engagements are not often shared. They are indirectly published in video overview form via YouTube.

| Title | Author(s) | Publication Date | Publisher | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Scaling of Adiabatic Compression of Field-Reversed Configuration Thermonuclear Fusion Plasmas | David Kirtley (CEO & Co-Founder Helion Energy); Richard Milroy (Research Professor Department of Aeronautics & Astronautics University of Washington) | 2023 | Springer Nature – Journal of Fusion Energy, Volume 42(2) | This paper investigates how adiabatic compression of FRC (Field-Reversed Configuration) plasma can be leveraged to reach relevant fusion conditions. Notably, Helion MIF fusion reactors leverage adiabatic compression in their central compression chamber. When the two plasmas pulsed from opposing ends of Helion’s symmetrical reactor collide, the magnetic fields rapidly reduce the plasma volume, resulting in a significant increase to the plasma internal temperature without the need for external heating. This paper argues that high beta plasma pulsed reactor operations result in adiabatic compression that allows the system to theoretically achieve energy gain while reducing the required confinement time. It does so by using adiabatic scaling laws derived from the Frist Law of Thermodynamics to prove fusion can be achieved via compression. |

| Creation of a high-temperature plasma through merging and compression of supersonic field reversed configuration plasmoids | John Slough, George Votroubek & Chris Pihl | 2011 | International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) – Nuclear Fusion, Vol 51(5) | This paper presents experimental results on the creation of high-temperature plasma through the merging and compression of two separate supersonic field reversed configuration (FRC) plasmoids. The experiment was conducted using an Inductive Plasma Accelerator (IPA). The study is a demonstration of the underlying physics Helion Energy’s reactor is based on and showed that colliding FRCs at high velocities enables rapid thermalization and magnetic reconnection, resulting in ion temperatures exceeding 1 keV and measurable fusion neutron production. Improved confinement and energy scaling suggest that this pulsed, magneto-kinetic approach can achieve fusion-relevant conditions in a compact device. These findings are directly relevant to Helion Energy's strategy to commercialize fusion energy, as they validate key physical mechanisms underlying Helion's pulsed FRC fusion concept. |

| Nuclear Propulsion through Direct Conversion of Fusion Energy: The Fusion Driven Rocket | John Slough, Anthony Pancotti, David Kirtley, Christopher Pihl, Michael Pfaff | 2012 | National Aeronautics and Space Administration – Phase I Final Report | This report presents a propulsion system built around a pulsed fusion cycle in which compact FRC plasmoids are formed, translated, and then compressed to fusion conditions using inductively driven metal liners. The study highlights that FRCs offer the ideal magnetized target for inertial-style compression. The physics analysis shows that modest liner velocities (~3–4 km/s) and sub-megajoule driver energies can produce meaningful fusion gain in a single pulse. Overall, the Phase I findings demonstrate that a magnetized-target FRC plasmoid, compressed inductively in short, repeatable pulses and allowed to expand for direct energy extraction, forms a technically plausible pathway to compact, high-efficiency fusion. |

¶ 10.2 Patents

| Title | Patent No. | Jurisdiction | CPC Classification(s) | Filing Date | Status* | Summary |

| Advanced Fuel Cycle and Fusion Reactors Utilizing The Same | US 11,469,003 | EP; ES; PL; CA; WO | G21B1/115 (Tritium Recovery); H05H1/14 (Plasma Confinement); Y02E30/10 (Nuclear Fusion Reactors) | 12 Jan 2017 | Issued 18 Oct 2022 | Protects Helion’s method of producing tritium and helium-3 as byproducts of D-D fusion, including chemical/cryogenic removal and storage of tritium gas as it decays to He-3. Enables fueling of high-beta plasma D–He3 reactors supporting direct energy recapture. |

| Apparatus and Methods for Generating a Pulsating, High-strength Magnetic Field | US 12,418,973 B2 | EP; AU; KR; WO; CN; CA | H05H1/14 (Plasma Confinement); G21B1/05 (Thermonuclear Reactors w/ Magnetic or Electric Plasma Confinement) | 04 Dec 2023 | Issued 16 Sep 2025 | Protects Helion’s pulsating magnetic field confinement and direct energy harvesting concept, including apparatus design for high-field coil architecture. |

| Energy Recovery in Electrical Systems | US20240275198A1 | JP; CN; KR; EP; WO; CA; AU | H02J7/0063 (Battery Charging Circuits); H02M1/34 (Snubber Circuits) | 03 Jun 2022 | Pending | Describes methods to recover and recycle energy in pulsed electrical systems by feeding captured energy back into the circuit to improve efficiency. |

| Monolithic High Field Magnets for Plasma Target Compression | US20240161963A1 | WO | H01F7/202 (Electromagnets for High Magnetic Field Strength) | 01 Dec 2023 | Pending | Protects a single-turn coil and supporting structure for generating intense magnetic fields to compress plasma targets. |

| Coatings on Inner Surfaces of Particle Containment Chambers | 20250201529 | WO; CN | H01J37/32486 (Reducing Recombination Coefficient); C23C16/4404 (Coatings Inside Reaction Chambers) | 16 Feb 2023 | Pending | Protects specialized surface coatings that resist plasma damage, extending reactor chamber lifespan. |

| Ceramic Fibers for Shielding in Vacuum Chamber Systems | 20240304424 | WO; CN; CA; EO | H01J37/32477 (Protection of Vessels / Internal Components) | 04 May 2024 | Pending | Protects use of ceramic fibers as shielding within reactor vacuum chambers for enhanced durability. |

* Status as of 27 October 2025

| Abbreviation | Jurisdiction |

|---|---|

| US | United States |

| EP | European Patent Office |

| ES | Spain |

| PL | Poland |

| CA | Canada |

| AU | Australia |

| KR | South Korea |

| CN | China |

| JP | Japan |

| WO | World Intellectual Property Organization (PCT) |

¶ 11. Technology Strategy Statement

Helion aims to deliver a commercially viable, defined as a sales cost of $0.01/kWh, Magneto-Inertial Fusion electricity reactor by 2030. To achieve the targeted 10 Hz repetition rate and near-ignition triple product, it is recommended that Helion continue its current R&D strategy, focusing on in-house manufacturing with the Omega facility and demonstrators for high-profile sponsors such as Microsoft. However, Helion also needs to pursue three additional R&D projects. The first project to prioritize is focused on superconducting magnets that should be implemented on the Orion Microsoft demonstrator in 2028 to increase the fuel's peak temperature towards the critical 58keV reactivity threshold. The second project Helion needs to add to its portfolio is an R&T project focused on cryogenic fuel injection, which will also aid in increasing the fuel's peak temperature. Finally, Helion needs to focus on creating a D-D fuel-producing reactor in 2030 that is operational in 2035 to reduce the payback period for Orion and the Nucor reactor from the nominal 14-year duration. This roadmap serves as the foundational technology for Helion and the FRC roadmap, which will necessitate the development of additional roadmaps for the identified R&T projects to ensure the firm's long-term goals and viability are secured.

¶ 12. Roadmap Maturity Assessment (optional)

As a cautionary note, this roadmap evaluates a technology that remains at a relatively low level of technical readiness and is still undergoing early commercialization efforts. These factors, in combination, result in limited and uneven data availability. Moreover, fusion is inherently complex, with many interdependent physical, engineering, and economic variables that are still evolving.

To make the analysis tractable, selective simplifications and assumptions were introduced. When such assumptions are made, they are explicitly stated within the relevant sections of the roadmap.

This document was drafted in November 2025 and reflects the state of the technology at that time. Given the rapid pace of progress in fusion, the date of authorship should be taken into account when interpreting the roadmap.

¶ 13. References

Helion Energy. (2025). Technology. Helion Energy. https://www.helionenergy.com/technology/

U.S. Department of Energy. (n.d.). Fusion energy. https://www.energy.gov/topics/fusion-energy

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT (GPT-5) [Large language model]. Retrieved September -November, 2025, from https://chat.openai.com/. Assistance for grammar correction, readability improvements, financial model Python code editing, and background research was provided using OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-5).

Kingham, David & Gryaznevich, Mikhail. (2024). The spherical tokamak path to fusion power: Opportunities and challenges for development via public–private partnerships. Physics of Plasmas. 31. 10.1063/5.0170088.

Walsh, S. (2024, December 20). Fusion energy’s strategic impact. Peak Nano. https://www.peaknano.com/blog/fusion-energys-strategic-impact

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024, July 15). U.S. energy facts explained. U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/

Hawker, N. (2020). A simplified economic model for inertial fusion. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 378(2189), 20200053. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2020.0053