Difference between revisions of "Hypersonic Transport Vehicles"

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

[[File:MaxVelocity_FOMPlot_Trendline_V3.png|700px|center]] | [[File:MaxVelocity_FOMPlot_Trendline_V3.png|700px|center]] | ||

The practical maximum flight speed for commercial aircraft is indicated at Mach 10, or approximately 7,700 mph. This limit exists because the time savings of supersonic and hypersonic flight become very limited at very high Mach numbers, as the vehicle spends the vast majority of a given flight accelerating and subsequently decelerating from its intended cruise speed. | The practical maximum flight speed for commercial aircraft is indicated at Mach 10, or approximately 7,700 mph. This limit exists because the time savings of supersonic and hypersonic flight become very limited at very high Mach numbers, as the vehicle spends the vast majority of a given flight accelerating and subsequently decelerating from its intended cruise speed. Reviewing the figure above, we argue that hypersonic commercial transport systems are in the incubation stage of their lifecycle. At present, no such vehicles exist, but the various research demonstrations show that we are approaching a point where hypersonic commercial transit can become a reality. Further, we are likely at the stagnation point of progress on traditional subsonic commercial vehicles. As such, for customers with enough capital to afford higher speed travel, hypersonic transport vehicles will likely eventually disrupt the commercial aviation market. If the timeline projected by the various concept vehicles is to be trusted, this disruption should occur in the early 2030s. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 15:55, 12 October 2023

Roadmap & System Overview

Hypersonic transport vehicles are a type of aircraft from the wider group of hypersonic systems. Hypersonic systems are all vehicles that operate in the flight regime where aerodynamic heating becomes significant, typically thought of as flight faster than Mach 5. Such systems include most atmospheric entry vehicles, some orbital launch vehicles, and several types of ballistic or maneuvering missiles. Hypersonic transport vehicles aim to move personnel and cargo from place to place much faster than traditional transonic or even supersonic aircraft. With a commercial application, this would be accomplished with the aim of generating profit for the company providing the transport service.

This page presents a technology roadmap for hypersonic transport vehicles. Hypersonic systems rely upon a myriad of sub-technologies that have allowed us to perfect flight at lower Mach numbers. Several of these existing technologies will be discussed here, in addition to a critical review of the technology advances still required to enable commercial hypersonic transport vehicles.

Boeing hypersonic airliner concept, from Wired, "Boeing’s Proposed Hypersonic Plane Is Really, Really Fast" by Eric Adams, published June 28, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/boeing-hypersonic-mach-5-jet-concept/

Design Structure Matrix Allocation

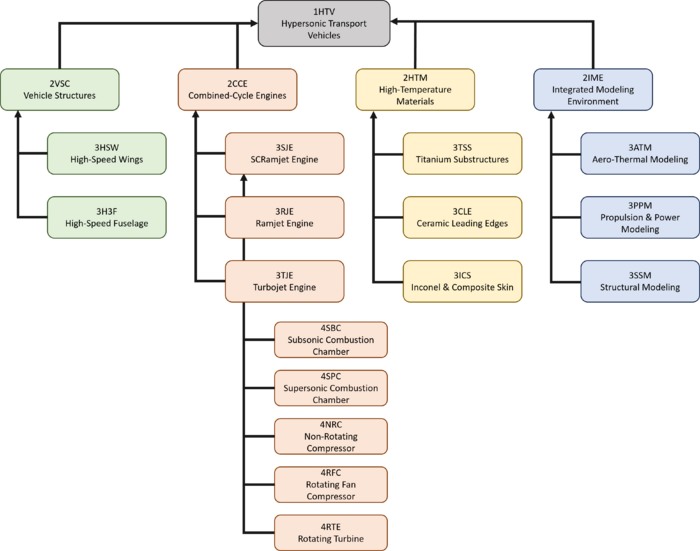

A hierarchical breakdown of a subset of the technologies required to enable the development of hypersonic transport vehicles is shown below. Note that the level 1 hypersonic transport vehicle technology is decomposed into four level two sub-technologies: vehicle structures, combined-cycle engines, high-temperature materials, and integrated modeling environments.

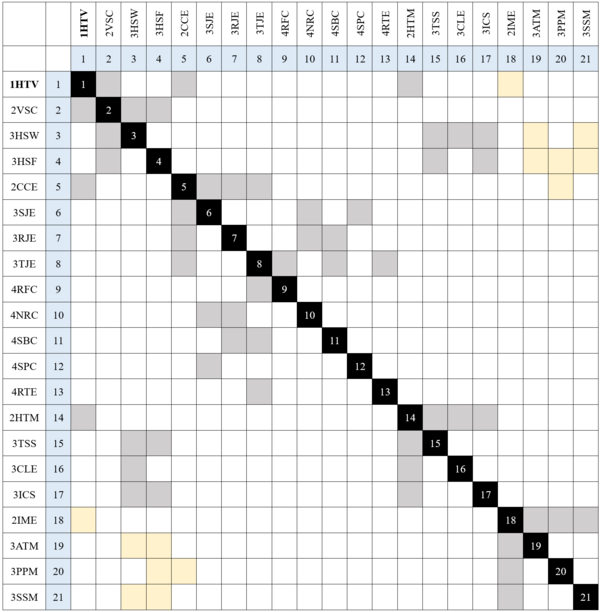

It is noted that several interactions exist between the various sub-technologies shown below. Such interactions are indicated in the design structure matrix (DSM), shown below. Interactions shown in grey represent either physical or component-type linkages (i.e. high-speed wings are part of hypersonic transport vehicles), whereas interactions in yellow represent information flows (i.e. aero-thermal analysis models are required for the development of high-speed wings).

Roadmap Model Using Object-Process Methodology (OPM)

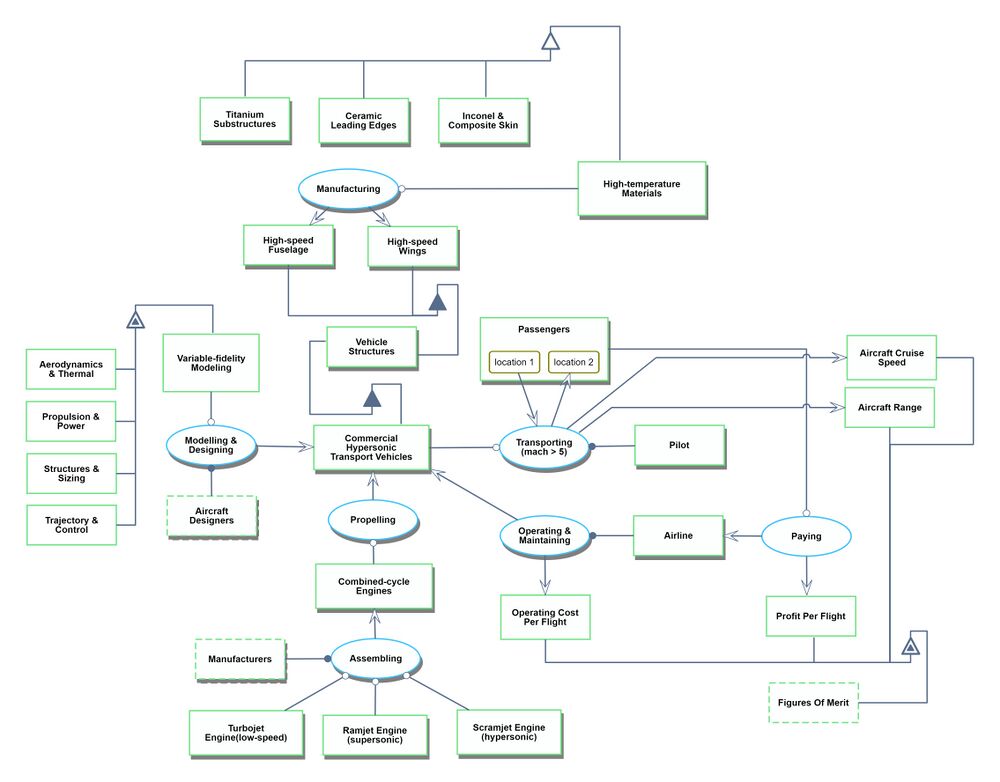

An OPM diagram showing a sample of the processes required for the creation and operation of commercial hypersonic transport vehicles is shown below. Note that the technology of interest (hypersonic transport vehicle) is shown near the center of the figures. The hypersonic transport vehicle serves to transport passengers from one location to another (also indicated near the center of the diagram). FOMs are shown towards the bottom right, with connections to relevant processes. It is noted that the sub-technologies shown in the diagram (high-temperature materials and structures, variable fidelity modeling, and combined-cycle engines) are discussed in detail by Bowcutt in [3].

Figures of Merit

The figures of merit (FOMs) relevant to commercial hypersonic transports include the distance covered per time (speed, v), aircraft range R, operating cost per flight C_O, the aircraft profit per flight p, the number of flights per aircraft, and the trans-Atlantic flight time. The profit p generated by the airline may be the single most important figure of merit, as it is the ultimate driver for the existence of commercial hypersonic vehicles (without profit, airlines will not offer such a service). These FOMs are described in the table below.

| Figure of Merit (FOM) | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Aircraft Speed | [m/s] | Maximum velocity of the aircraft during the flight. Correlates to cruise velocity for hypersonic commercial transport vehicles. |

| Aircraft Range | [m] | Maximum distance traveled per flight at maximum payload capacity. |

| Operating Cost | [$] | Cost per flight to operate the aircraft. Function of the personnel (pilot and crew) cost, fuel cost and post-flight refurbishment required prior to future flights. |

| Profit per Flight | [$] | Function of the number of passengers, price per ticket, operating cost and overall programmatic cost. |

| Flights per Aircraft | [n] | Number of flights will be limited by structural fatigue due to system cycles. |

| Trans-Atlantic Flight Time | [hrs] | A function of aircraft velocity that captures the transitions between takeoff, cruise, and landing phases of flight. Because of the length of the transient phases (takeoff and landing), this FOM more directly correlates to the benefit to the consumer than the aircraft velocity FOM. |

The FOMs above are described mathematically, including expected nominal values in the table below.

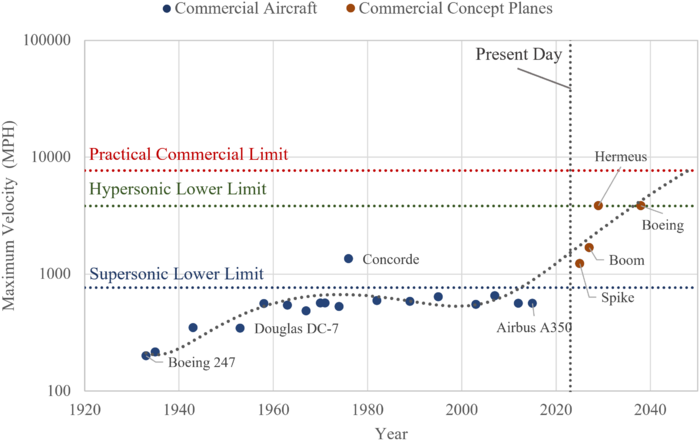

It is possible to review historic trends of the FOMs by plotting the FOM value of a given system over time. In the figure below, we plot the maximum velocity of various existent commercial aircraft and projected commercial aircraft concepts.

The practical maximum flight speed for commercial aircraft is indicated at Mach 10, or approximately 7,700 mph. This limit exists because the time savings of supersonic and hypersonic flight become very limited at very high Mach numbers, as the vehicle spends the vast majority of a given flight accelerating and subsequently decelerating from its intended cruise speed. Reviewing the figure above, we argue that hypersonic commercial transport systems are in the incubation stage of their lifecycle. At present, no such vehicles exist, but the various research demonstrations show that we are approaching a point where hypersonic commercial transit can become a reality. Further, we are likely at the stagnation point of progress on traditional subsonic commercial vehicles. As such, for customers with enough capital to afford higher speed travel, hypersonic transport vehicles will likely eventually disrupt the commercial aviation market. If the timeline projected by the various concept vehicles is to be trusted, this disruption should occur in the early 2030s.

References

[1] Hayward, J. and Ahlgren, L., “The Cost of Flying: What Airlines have to Pay to get you in the Air,” Simple Flying, 26 May 2023, https://simpleflying.com/the-cost-of-flying/.

[2] Gray, S., “Here’s how much Airlines are Profiting off your Plane Ride,” Money, 14 Feb. 2018, https://money.com/airline-profit-per-passenger/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Wall%20Street,airlines%20was%209%25%20in%202017.

[3] Bowcutt, K. G., “Flying at the Edge of Space and Beyond: The Opportunities and Challenges of Hypersonic Flight,” National Academy of Engineering, 25 June 2020, https://www.nae.edu/234431/Flying-at-the-Edge-of-Space-and-Beyond-The-Opportunities-and-Challenges-of-Hypersonic-Flight#:~:text=decades%20to%20come.-,Flying%20at%20the%20Edge%20of%20Space%20and%20Beyond%3A%20The,and%20Challenges%20of%20Hypersonic%20Flight&text=The%20primary%20benefit%20of%20hypersonic,hours%2C%20or%20achieve%20Earth%20orbit.

[4] Rodrigue, J.-P. (2020). The geography of transport systems (Fifth edition). Routledge Taylor

& Francis Group.

[5] “Boeing Model 247.” Http://Www.aviation-History.com/Boeing/247.Html, The Aviation

History On-Line Museum, 17 Apr. 2022, www.aviation-history.com/boeing/247.html.

Accessed 4 Oct. 2023.

[6] “Celebrating Concorde | Information | British Airways.” Britishairways.com, 2023,

www.britishairways.com/content/en/de/information/about-ba/history-and- heritage/celebrating-concorde. Accessed 4 Oct. 2023.

[7] “Railway Speed Record.” Wikipedia, 28 Sept. 2023,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Railway_speed_record. Accessed 5 Oct. 2023.

[8] Hayward, J. and Ahlgren, L., “The Cost of Flying: What Airlines have to Pay to get you in the Air,” Simple Flying, 26 May 2023, https://simpleflying.com/the-cost-of-flying/.

[9] Gray, S., “Here’s how much Airlines are Profiting off your Plane Ride,” Money, 14 Feb. 2018, https://money.com/airline-profit-per-passenger/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Wall%20Street,airlines%20was%209%25%20in%202017.

[10] Bowcutt, K. G., “Flying at the Edge of Space and Beyond: The Opportunities and Challenges of Hypersonic Flight,” National Academy of Engineering, 25 June 2020, https://www.nae.edu/234431/Flying-at-the-Edge-of-Space-and-Beyond-The-Opportunities-and-Challenges-of-Hypersonic-Flight#:~:text=decades%20to%20come.-,Flying%20at%20the%20Edge%20of%20Space%20and%20Beyond%3A%20The,and%20Challenges%20of%20Hypersonic%20Flight&text=The%20primary%20benefit%20of%20hypersonic,hours%2C%20or%20achieve%20Earth%20orbit.

[11] Rodrigue, J.-P. (2020). The geography of transport systems (Fifth edition). Routledge Taylor

& Francis Group.

[12] “Boeing Model 247.” Http://Www.aviation-History.com/Boeing/247.Html, The Aviation

History On-Line Museum, 17 Apr. 2022, www.aviation-history.com/boeing/247.html.

Accessed 4 Oct. 2023.

[13] “Celebrating Concorde | Information | British Airways.” Britishairways.com, 2023,

www.britishairways.com/content/en/de/information/about-ba/history-and- heritage/celebrating-concorde. Accessed 4 Oct. 2023.

[14] “Railway Speed Record.” Wikipedia, 28 Sept. 2023,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Railway_speed_record. Accessed 5 Oct. 2023.

[15] Independent Market Study for Commercial Hypersonic Transportation. Deloitte Consulting, Apr. 2021.