Difference between revisions of "Autonomous Mobile Robots for Enhancing Warehouse Logistics"

Tag: Manual revert |

|||

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

<b>FOM1: Picking rate of AMR</b> | <b>FOM1: Picking rate of AMR</b> | ||

[[File:3AMR_FOM1_equations.png|600px]] [[File:3AMR_FOM1_variables.png|240px]] | |||

=Key Publications, Presentations, and Patents= | =Key Publications, Presentations, and Patents= | ||

Revision as of 03:03, 4 November 2024

Roadmap Overview

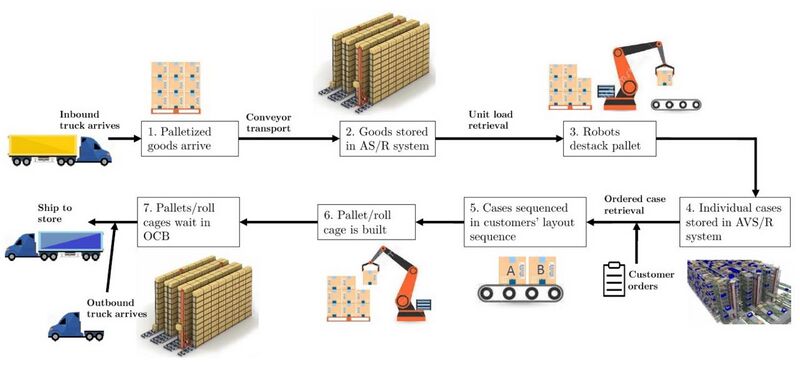

Warehouses are dynamic environments that have evolved into automated facilities designed to process, store, and ship products to customers around the world. These facilities play a key role in the logistics and supply chain networks for large-scale businesses. To meet the growing demands for speed and accuracy of today’s shipping expectations, significant advancements have been made to improve security, inventory management, storage optimization, climate control, and people management in warehouses. Figure 1 provides an overview of the basic processes that occur within a warehouse and points out some of the areas robotics are used to streamline product movement through the warehouse and enhance operational efficiency.

A lot of technology has been developed over the last several decades to optimize logistics and advance the operations within a warehouse. One of the largest challenges warehouses face is how to lift and transport heavy materials. Before the 1950s, this was primarily done through the use of carts on fixed rail systems or vehicles operated by humans. While these solutions helped to solve the transport problem, they introduced new issues around maintenance and fixed infrastructure as well as safety and training for employees and operators. In the 1950s, automated guided vehicles (AGVs) were introduced to warehouses. These vehicles were able to transport materials without the need for an operator, but still required the installation of a mechanism to guide the vehicles along a specified path. Initially, the guide was a set of wires that induced a magnetic field that would propel a cart along its path. This quickly evolved to utilize magnetic tape, optical strips, and eventually laser guidance. These systems are still in use today and provide a reliable mechanism to transport goods around a warehouse; however, they don't have the adaptability and intelligence needed for modern warehouse operations [4].

While AGVs were evolving, so was the field of robotics, specifically autonomous mobile robots (AMRs). AMRs are a class of robots that have the ability to sense their surroundings and intelligently navigate a dynamic environment to accomplish a task [6]. The first set of AMRs were developed by William Grey Walter in the 1940s and 1950s. He developed two robots named Elmer and Elsie for use in neurophysiology research. These robots were equipped with light and touch sensors, and eventually included the ability to sense sound and move around. Between the 1950s and 1990s, AMRs continued to evolve, but were primarily used in research and academia. The HelpMate was the first AMR that was commercially available. This robot was released in the 1990s and featured Sonar, infrared, and vision systems. The HelpMate was used to transport materials around medical facilities [3]. Now, companies like Amazon Robotics (formerly Kiva Systems) and inVia are developing advanced robotics to facilitate dynamic operations within a warehouse while reducing safety incidents and increasing productivity.

In this roadmap, we will attempt to address and characterize a technology aimed at reducing warehouse complexity in three key areas – storage optimization, product movement, and people management.

There are several different types of robots that are currently in use or being developed for warehouses today. Each type of robot has a specific function or a few specific functions within a warehouse. Table 1 provides an overview of the primary robots in use today.

| Type | Use Case | High Level Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Robotic Arms | Loading or picking up boxes | * End-of-arm tools * Vacuum grippers * Joint actuators * Computer vision * Cameras * Sensors * Controller * Power systems |

| Packaging Robots | Packing and sealing boxes | * Boxing robotics * Labeling mechanics |

| Verification Robots | Scanning products and/or packages | * 3D scanners * Barcode/QR scanners |

| Autonomous Mobile Robots | * Lift and transport goods to humans * Optimize storage patterns |

* LiDAR * Sensors * Digital Twins * Machine Learning * Optimization algorithms * Communications systems * Motor * Battery systems |

Autonomous mobile robots and their use within warehouse systems will be the primary focus for our roadmap. These devices combine several advanced technologies to transport goods without the assistance of humans or guides. They help to reduce safety incidents, increase picking rates, and increase fulfillment rates within warehouses. Throughout the rest of this roadmap, we will do a comprehensive review of AMRs and their enabling technologies.

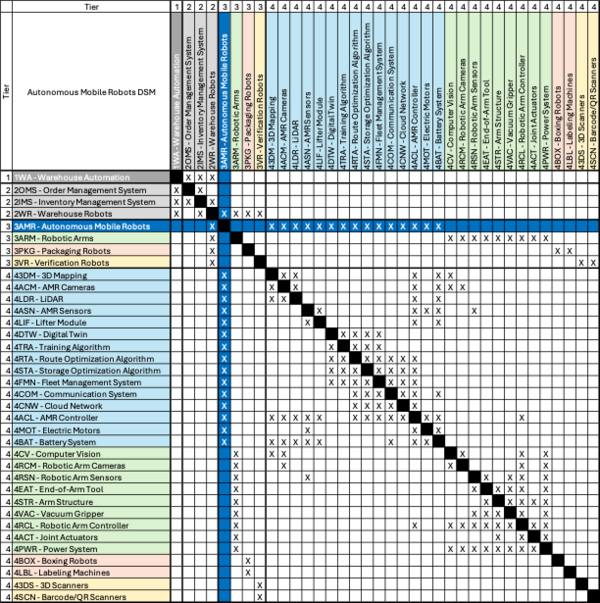

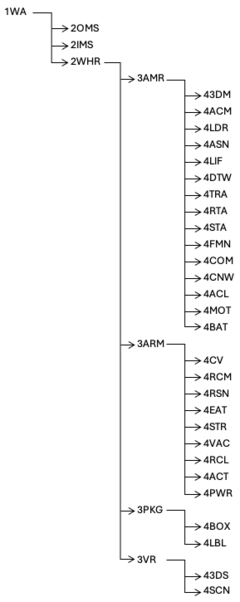

Design Structure Matrix (DSM) Allocation

We present here the DSM allocation of autonomous mobile robots and its tree. The company-wide initiative of warehouse automation is supported by the order management system, the inventory management system, and warehouse robots. Warehouse robots can be classified into autonomous mobile robots, robotic arms, packaging robots, and verification robots. We focus on the autonomous mobile robot for this roadmap, which is enabled by level 4 technologies in light blue, such as 3D mapping, digital twins, and route optimation algorithms. The DSM shows coupling between technologies; for example, the development of the lifter module is dependent on the performance of sensors, the controller, and the battery system.

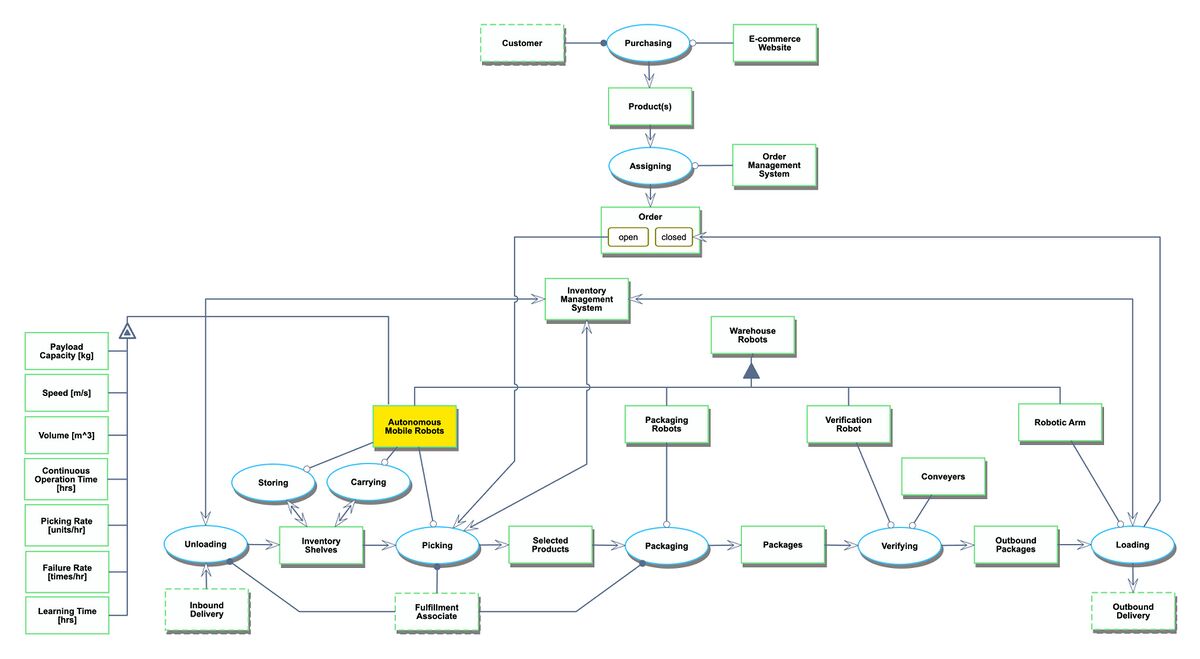

Roadmap Model using OPM

The OPM for warehouse automation and the role of autonomous mobile robots is shown below. In preparation for warehouse operations, inbound delivery to the warehouse is unloaded and stored in inventory shelves that are carried by AMRs. When a customer purchases a product on the e-commerce website, the order management system assigns an order to the warehouse, which initiates the picking and packaging processes: AMRs carry themselves to the fulfillment associate who picks the purchased products, packaging robots assist the fulfillment associate in packaging, packages are transported on conveyor belts as they are verified (scanned) by verification robots, and finally the outbound packages are loaded onto trucks by robotic arms and shipped out as outbound delivery. Throughout the process, the inventory management system tracks the inventory in the warehouse at the unloading, picking, and loading stages.

Figures of Merit (FOM)

Below are key FOMs for autonomous mobile robots. Payload capacity, speed, and picking rate are FOMs that contribute to the efficiency of warehouse automation. Continuous operation time and failure rate determine the robustness of AMRs. Volume of AMR can also be a competitive metric as AMRs operate in warehouses that are limited in space. Learning time indicates the time it takes to train the AMR in a digital twin before deploying them into the physical warehouse.

| Figure of Merit (FOM) | Unit | Description | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Payload Capacity | [kg] | Total weight the AMR can carry (including items and shelves) | Increasing |

| Speed | [m/s] | Average speed of the AMR while carrying shelves inside the warehouse | Increasing |

| Volume | [m^3] | Volume of AMR (width x length x height) | Decreasing |

| Continuous Operation Time | [hrs] | Total time the AMR can operate in one full charge | Increasing |

| Picking Rate | [units / hr] | Number of units picked and delivered to fulfillment associate per hour | Increasing |

| Failure Rate | [times/ hr] | Number of times the AMR fails per hour | Decreasing |

| Learning Time | [hrs] | Total time it takes to train the AMR to operate in a warehouse | Undetermined |

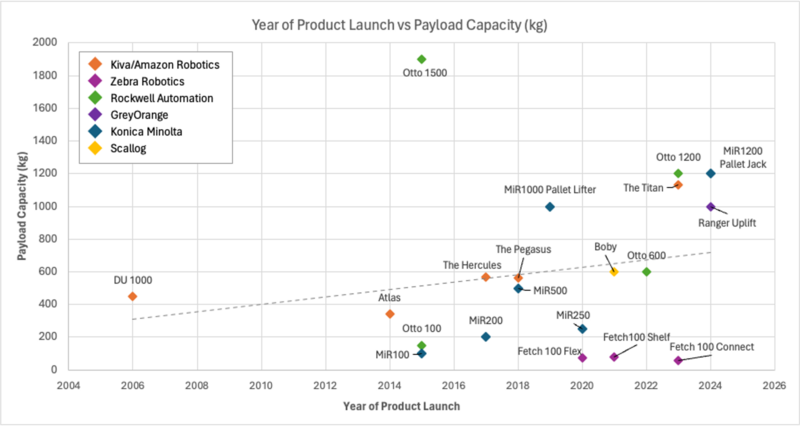

Following is the trend of payload capacity for AMRs by various manufacturers developed since 2006, where we can see a steady improvement in performance.

Alignment with Company Strategic Drivers

Positioning of Company vs. Competition

The images and table below show examples of AMRs available on the market today along with representative data points for key figures of merit that AMRs are evaluated upon.

| Company | Robot | Date Released | Load Capacity (kg) | Volume (m^3) | Load Capacity / Volume (kg/m^3) | Weight (kg) | Load Capacity / Weight | Speed (m/s) | Battery Life (hr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kiva/Amazon Robotics | DU 1000 | 2006 | 450 | 0.14 | 3,333 | 110 | 4.09 | 1.39 | * |

| Kiva/Amazon Robotics | The Hercules | 2017 | 567 | * | 340 | 1.67 | * | * | * |

| Kiva/Amazon Robotics | The Pegasus | 2018 | 560 | 0.09 | 6,550 | 60 | 9.33 | * | * |

| Kiva/Amazon Robotics | Titan | 2023 | 1,134 | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Kiva/Amazon Robotics | Atlas | 2014 | 340 | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Zebra Robotics | Fetch 100 Flex | 2020 | 75 | 0.48 | 154 | 91 | 0.83 | 1.74 | 9 |

| Zebra Robotics | Fetch 100 Connect | 2023 | 57 | 0.15 | 375 | 74 | 0.77 | 1.50 | 9 |

| Zebra Robotics | Fetch100 Shelf | 2021 | 78 | 0.48 | 161 | 91 | 0.86 | 1.75 | 9 |

| Rockwell Automation | Otto 100 | 2015 | 150 | 0.13 | 1,173 | 93 | 1.61 | 2.00 | 6 |

| Rockwell Automation | Otto 600 | 2022 | 600 | 0.24 | 2,551 | 290 | 2.07 | 1.40 | * |

| Rockwell Automation | Otto 1200 | 2023 | 1,200 | 0.39 | 3,053 | 4,200 | 0.29 | 1.50 | * |

| Rockwell Automation | Otto 1500 | 2015 | 1,900 | 0.82 | 2,305 | 820 | 2.32 | 2.00 | 10 |

| GreyOrange | Ranger Uplift | 2024 | 1,000 | 0.41 | 2,426 | * | 2.00 | * | * |

| Konica Minolta | MiR100 | 2015 | 100 | 0.18 | 553 | 65 | 1.54 | 1.50 | 10 |

| Konica Minolta | MiR200 | 2017 | 200 | 0.18 | 1,107 | 65 | 3.08 | 1.50 | 10 |

| Konica Minolta | MiR500 | 2018 | 500 | 0.40 | 1,258 | 230 | 2.17 | 2.00 | 8 |

| Konica Minolta | MiR1000 Pallet Lifter | 2019 | 1,000 | 1.77 | 564 | * | * | 8 | * |

| Konica Minolta | MiR250 | 2020 | 250 | 0.14 | 1,796 | 94 | 2.66 | 2.00 | 20 |

| Konica Minolta | MiR1200 Pallet Jack | 2024 | 1,200 | 3.15 | 381 | * | 1.50 | 8 | * |

| Scallog | Boby | 2021 | 600 | 0.29 | 2,051 | 150 | 4.00 | 1.50 | 14 |

*This data is not publically available and is most likely a trade secret.

Technical Model

To understand the sensitivity of FOMs to the decisions we make in the morphological matrix, we derived the technical model of two FOMs: picking rate and continuous operation time.

FOM1: Picking rate of AMR

File:3AMR FOM1 equations.png File:3AMR FOM1 variables.png

Key Publications, Presentations, and Patents

The following are a representative set of patents and papers that have contributed to the overall development of AMRs:

1. Patient #US 7,402,018 B2 – Inventory System with Mobile Drive Unit and Inventory Holder

2. Patient #US 7,873,469 B2– System and Method for Maneuvering a Mobile Drive Unit

3. Patent #US 8,280,547 B2 – Method and System for Transporting Inventory Items

4. Martins, V. F., Silva, F. J. G., & Monteiro, F. (2021). A Digital Twin Approach for the Improvement of an Autonomous Mobile Robot's (AMR) Operating Environment: A Case Study. Retrieved October 29, 2024, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356528334

5. Nilsson, N. J. (1984). Shakey the robot. AI Center, SRI International. Retrieved November 1, 2024, from https://www.cs.sfu.ca/~vaughan/teaching/415/papers/shakey.pdf

Patent: Inventory System with Mobile Drive Unit and Inventory Holder

Patent #: US 7,402,018 B2

Date of Patent: Jul. 22, 2008

Patent Owner: Amazon Technologies Inc (formerly Kiva Systems, Inc.)

CPC Classification:

- International Classification: B62B II/00

- US Classification: 414/331.06.211/95. 28.047.35

Details: Patent US 7,402,018 B2 describes a system for transporting inventory that includes an inventory holder and a mobile drive unit. It is designed for environments like warehouses and manufacturing facilities. The system operates by using the mobile drive unit to autonomously dock with the inventory holder and transport it to specified locations within a workspace. The patent shows figures explaining the system configuration and includes process flow diagrams and descriptions to explain how the system operates once it wirelessly receives orders which trigger a series of commands.

Relevancy: This system is relevant because of its ability to streamline operations in automated environments, reduce labor costs, improve warehouse efficiency, and adapt to dynamic inventory demands, which addresses many limitations of traditional, rigid automated inventory systems that are not scalable. The system can also be operated with minimal human effort.

Patent: System and Method for Maneuvering a Mobile Drive Unit

Patent #: US 7,873,469 B2

Date of Patent: Jan. 18, 2011

Patent Owner: Amazon Technologies Inc (formerly Kiva Systems, Inc.)

CPC Classification:

- International Classification: G01C 21/32

- US Classification: 701/209; 701/202; 340/988, 995.19

Details: Patent US 7,873,469 B2 describes a procedure for navigation of a mobile drive unit. There are several workflows outlined in the patent - how to generate and reserve a route once a task has been received, how to proceed on the route reserving small segments at a time, and how to reroute if a segment is already reserved by another unit. It includes a series of procedural diagrams that outline each step in the routing and maneuvering process. Additionally, there is a series of illustrations demonstrating the layout of a warehouse and various hypothetical routes and situations.

Relevancy: Effectively navigating a space is critical to the function of AMRs in a warehouse. This patent describes a procedure that allows AMRs to navigate through a warehouse on an optimized path without running into other AMRs. This helps increase picking rates and decrease failures.

Patent: Method and System for Transporting Inventory Items

Patent #: US 8,280,547 B2

Date of Patent: Oct. 2, 2012

Patent Owner: Amazon Technologies Inc (formerly Kiva Systems, Inc.)

CPC Classification:

- International Classification: G06F 7700

- US Classification: 700/214

Details: Patent US 8,280,547 B2 describes a method and system designed to autonomously navigate to transport inventory with the mobile drive unit. The drive unit can move to a specific point with the inventory holder either attached or supported. It determines the inventory holder’s location and checks if it deviates beyond a set tolerance from the desired point. If the deviation is too large, the mobile drive unit moves to a new position, docks with the inventory holder, and then returns to the intended location.

Relevancy: This patent is relevant as it addresses the system’s ability to ensure precise positioning and movement of inventory within a warehouse or fulfillment center, which is crucial for efficient operations. By automatically correcting deviations in the inventory holder’s location, the system maintains organized flow and minimizes human intervention, thereby increasing the accuracy, speed, and reliability of inventory management in automated environments.

Paper: Shakey the Robot

Author(s): N J Nilsson

Organization: Artificial Intelligence Center

Details: This paper is a compilation of excerpts from Stanford Research Insititute that describe the development and abilities of a mobile robot named Shakey (the second Shakey system) between 1966 and 1972. The excerpts cover Shakey’s key components (hardware and software), “world model” (a model that represented Shakey's surroundings), low-level actions, intermediate-level actions, STRIPS (the Stanford Research Insititute Problem Solver which enabled Shakey to generate plans to accomplish tasks), vision routines, ability to extract patterns from previous plans and apply learnings to new plans, as well as Shakey’s limitations. Experiments near the end of the paper further describe Shakey’s ability to navigate and handle obstacles as well as perform simple tasks.

Relevancy: This paper has played a major role in the evolution and development of autonomous robots. It laid the ground work autonomous navigation and reasoning in robots. This paper has been cited approximately 1,273 times according to google scholar and continues to be a reference point for researchers and scientists in robotics and artificial intelligence today.

Citation: Nilsson, N. J. (1984). Shakey the robot. AI Center, SRI International. Retrieved November 1, 2024, from https://www.cs.sfu.ca/~vaughan/teaching/415/papers/shakey.pdf

References

[1] Azadeh, K., de Koster, R., & Roy, D. (n.d.). Material flow in a typical automated warehouse [Figure 1]. In Robotized and Automated Warehouse Systems: Review and Recent Developments. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2977779:contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}.

[2] Conveyco. (n.d.). Autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) [Image]. Retrieved October 9, 2024, from https://www.conveyco.com/technology/autonomous-mobile-robots-amrs/

[3] Goodwin, D. (2020, September 9). The evolution of autonomous mobile robots. Control. Retrieved October 9, 2024, from https://control.com/technical-articles/the-evolution-of-autonomous-mobile-robots/

[4] inVia Robotics. (n.d.). Autonomous warehouse robots: A brief history. Retrieved October 9, 2024, from https://inviarobotics.com/blog/autonomous-warehouse-robots-brief-history/

[5] Nilsson, N. J. (1984). Shakey the robot. AI Center, SRI International. Retrieved November 1, 2024, from https://www.cs.sfu.ca/~vaughan/teaching/415/papers/shakey.pdf

[6] Raj, R., & Kos, A. (2022). A comprehensive study of mobile robot: History, developments, applications, and future research perspectives. Applied Sciences, 12(14), 6951. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12146951

Figure 5:

[1] AllAboutLean.com. (n.d.). *The Amazon robotics family: Kiva, Pegasus, Xanthus, and more...* All About Lean. https://www.allaboutlean.com/amazon-robotics-family/

[2] Amazon. (n.d.). *The story behind Amazon's next generation robot*. About Amazon. https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/operations/the-story-behind-amazons-next-generation-robot

[3] Amazon. (n.d.). *Amazon robotics unveils Titan, new fulfillment center robot*. About Amazon. https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/operations/amazon-robotics-unveils-titan-new-fulfillment-center-robot

[4] Zebra Technologies. (n.d.). *Fetch100 Flex*. [Brochure]. Zebra Technologies. https://www.zebra.com

[5] Zebra Technologies. (n.d.). *Robotics automation brochure portfolio*. [Brochure]. Zebra Technologies. https://www.zebra.com

[6] OTTO Motors. (n.d.). *OTTO 100 autonomous mobile robot*. Rockwell Automation. https://ottomotors.com

[7] OTTO Motors. (n.d.). *OTTO 600 autonomous mobile robot*. Rockwell Automation. https://ottomotors.com

[8] OTTO Motors. (n.d.). *OTTO 1200 autonomous mobile robot*. Rockwell Automation. https://ottomotors.com

[9] OTTO Motors. (n.d.). *OTTO 1500 autonomous mobile robot*. Rockwell Automation. https://ottomotors.com

[10] GreyOrange. (n.d.). *Intralogistics (IL) AMR*. https://www.greyorange.com

[11] Hartfiel Automation. (n.d.). *MiR100 mobile robot*. https://shop.hartfiel.com/products/MiR100%20Mobile%20Robot

[12] Hartfiel Automation. (n.d.). *MiR200 mobile robot*. https://shop.hartfiel.com/products/MiR200%20Mobile%20Robot

[13] Hartfiel Automation. (n.d.). *MiR500 mobile robot*. https://shop.hartfiel.com/products/MiR500%20Mobile%20Robot

[14] Hartfiel Automation. (n.d.). *MiR1000 pallet lifter*. https://shop.hartfiel.com/products/MiR1000%20Pallet%20Lifter

[15] Mobile Industrial Robots. (n.d.). *MiR250*. https://mobile-industrial-robots.com/products/robots/mir250

[16] Mobile Industrial Robots. (n.d.). *MiR1200 pallet jack*. https://mobile-industrial-robots.com/products/robots/mir1200-pallet-jack

[17] Scallog. (n.d.). *Logistics robot for autonomous product movement*. https://www.scallog.com