On Orbit Refueling Repositioning

Welcome to the 3OORR - On Orbit Refueling and Repositioning technology roadmap page.

Our designator 3OORR denotes this is a "level 3" technology decomposition, providing analysis to the on-orbit refueling and repositioning subsystem level. This product is intended to be an iterative document that will be updated when new data becomes available.

Roadmap Overview

On-orbit refueling and repositioning (OOR) is rooted in the need to alter spacecraft and their orbital parameters after launch. Dating back to applications for the Russian Mir Space Station and early uses for the International Space Station (ISS), OOR has taken many forms during the space age. Recent interest in the need to refuel and reposition satellites for reasons ranging from adhering to deorbit laws to wanting to extend functional satellite lifetimes has increased the need to understand OOR and predict its maturation. To this end, this technology roadmap (TRM) focuses on the capability to refuel and reposition satellite systems in orbit. This roadmap considers both traditional systems (e.g. space station resupply missions including astronaut support) as well as modernized methods (e.g. autonomous/robotic refueling operations). To carry out this analysis, a level 1 roadmap of the OOR global marketplace is captured, allowing a level 2 analysis of specific OOR products and services, which is complemented by a level 3 decomposition of OOR subsystems and components.

DSM Allocation (Interdependencies With Others Roadmaps)

When attempting to roadmap any technology, it is highly beneficial to map interdependencies of other roadmaps and related technologies. This approach educates the architects on the system and subsystem components while also informing viewers of strong dependencies, technology pushers and pullers, and items that may have the strongest benefit to performance if improved. To this end, a DSM of OOR satellite systems is shown to the right. Items noted on the rows are denoted as providing an output (fulfilling a dependency), while items in the vertical columns receive an input from the associated row (requiring a dependency). This approach to graphically representing their dependencies and relationships within the system allows an easier understanding of regions of high overlap as well as technologies that are isolated. The tiers of this analysis are broken down into the following categories:

Tier 1: OOR System

Tier 2: OOR Subsystem Components

Tier 3: OOR Corresponding Subcomponents of All Tier 2 Items

Upon viewing the results shown in the DSM diagram, there are multiple notable insights gained:

- Client Satellite Needs Can Highlight Key Stakeholder Needs

- Client satellites are one of the largest technology “pullers” in the DSM, highlighting their representation of stakeholder's needs and potential impact in advancing the receptivity and compatibility of client systems.

- Command & Control is a Technology Pusher & Puller

- Command and control (C2) of systems, for both launch vehicle and satellite systems, are a dominant reliance within the system (red boxes). C2 serves as both a strong technology pusher as well as a puller, highlighting the potential impact on OOR capabilities if advancements are seen in C2 capabilities/technologies.

- Client-Servicer Satellite Compatibility is a Key Characteristic

- The compatibility of refueler/servicer and client satellite systems (yellow box) is a strong dependency that will likely require coordination and standardization to sustain improved technology development and maturation.

- Human vs. Robotic Functions Both Have Pros & Cons

- The transition from astronauts to autonomous/robotic systems transfers dependencies, further increasing C2 needs while reducing the risk of life/limb, and likely reducing overall mission cost.

Using the knowledge gained from generating this DSM, the authors believe advancements in the following related technologies will have great benefit to the maturation of OOR systems:

- Launch Vehicle Technology

- C2 Capabilities

- Satellite Autonomous Functions

- Space Robotics

- Remote Proximity Operations (RPO)

- Standardized Docking Interfaces

Harnessing the knowledge gained from this DSM and the above technological areas of potential high impact, this information can be used to inform our search for patents, prototypes, designs, and competition in the OOR tradespace. This honed research will aid in informing later steps of this technology roadmap. Next and more directly, the results of this DSM are modeled in OPM to create an OPM diagram of OOR, allowing us to relate dependencies to the form, function, flow, and make-up of OOR systems.

Roadmap Model Using OPM (ISO 19450)

The next step in the TRM process is to build a better understanding of the functional flow, form, relationships, and interactions between the critical components of an OOR system. To achieve this, an OPM diagram of On-Orbit Refueling was generated using OPCloud. Again, through the use of a pictorial representation of our system, we can more easily see some of the defining characteristics of our system:

- Limited Physical Items in the System

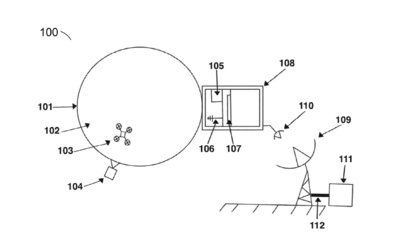

- One fundamental takeaway from this diagram is that there are limited physical aspects within the system, including the two satellites, operational ground stations, and the launch vehicle (which is outside the boundary of the system but still affects it). The complexity of the servicing and client satellite systems is emphasized here.

- FOMs are Ommitted but Tied to Functions (Blue Circles)

- Notably, the Figures of Merit (FOMs) were not included in this diagram and instead are covered in the next section of this webpage. That said, the intent behind the FOMs is captured through the functionality provided by the blue circles in the OPM diagram.

- Client-Servicer Compatibility is a Key Consideration

- The traceability of key functions in this OPM diagram draws attention to the docking, interfacing, and overall compatibility of the servicer and client satellite systems.

The functional takeaway from this figure is that refueling is the action being completed, which transits and transfers fuel from the servicer satellite to the client satellite. This fulfills the need to refuel/reposition the client satellite so that it may maneuver for a longer period of time (fixing the problem of not being able to maneuver without additional fuel). Items that are in dashed boxes still impact the system under consideration but are considered outside the scope/boundary of the system itself. It is powerful to provide traceability between the DSM and OPM diagram approaches, as we see in this technology. The combined importance of servicer and client compatibility, seen in both the dependencies of the DSM and the operational flow of the OPM diagram, further emphasizes the importance of mating, docking, and satellite compatibility as an enabler for broader OOR advancement. The exclusion of "developing & manufacturing", "launch vehicle", and "launching", from the system boundary was made to ensure that the technological considerations are rooted in OOR advancements. That considered, the authors also note that advancements in launch technology directly impact the potential benefits and capability space of OOR, and should be closely tracked to determine cost and performance implications.

Figures of Merit (FOM)

To qualitatively track the technological progression of OOR, it is necessary to select metrics that can capture the progression rate of specific technological characteristics. Looking at the figures of merit selected for OOS, figures were chosen to track the technology's progression over time that captured stakeholder needs, used quantifiable engineering metrics, and were derived from available data. The table below displays the selected FOMs for OOR and descriptions of each figure, with more detailed descriptions and intent of each provided after the table.

FOM Generation Background/Intent

- (Refueling Cost / KG Fuel Delivered)

- The selection of this metric is considered a fundamental quantitative metric for tracking the cost associated with the potential benefits of refueling satellites on orbit. "Cost" in this context includes two potentially different values depending upon the type of program being considered. For commercial services, the price charged/advertised to customers per kg of fuel delivered is directly used for the value. For Research & Development (R&D) missions, the total mission cost was used as the monetary value, divided by the toal mass of fuel transferred to customer satellites. This figure aids in determining the market interest in services as well as the advancement in manufacturing and providing refueling, where lower values assume companies are able to provide the service at a sustained profit by harnessing advancements in technology.

- (% Customer Lifetime Extension)

- This metric is a notable deviation from other approaches to capturing OOR value, which commonly harness fuel transferred (in KG). Although a KG-of-fuel metric can be beneficial and should still be tracked, the authors elected to harness a more holistic value to capture differences in fuel types and thrusters (e.g. chemical vs. electric propulsion), satellite sizes, and intended lifecycle use. By capturing the percentage that a customer's satellite lifetime is extended, the total mass transferred to customer satellites can be captured in a more informative manner. Lifetime extension percentages can grow well over 100% if a satellite is refueled or repositioned multiple times, with that value being captured via utility-oriented percentage and not simply a kg value of fuel.

- (Fuel-Mass-Ratio of Servicing Satellite)

- To capture the advancements made in space refueling technology as well as the intent to "optimize" refueling satellite systems, the ratio of servicer satellite fuel (in KG) to the total servicer satellite mass (in KG) was tracked and compared. This ratio highlights missions that are experimental in nature or those that have multiple intended objectives for a single satellite. By highlighting these missions, they can be independently considered for inclusion or omission, allowing a honed focus on OOR missions with intentions of advancing the state-of-the-art in OOR or maximizing fuel transferred on orbit. This metric approach allows an engineering-backed filtering of OOR space missions, believed to be more accurate at tracking and predicting OOR technology maturation.

- (Mean Fuel Transfer Rate)

- By tracking the mean time to transfer fuel between a client and servicer satellite, real-world considerations can be captured in the use of OOR systems. With this time including docking and fuel transfer, systems that are incompatible can be highlighted as well as those with designed direct compatibility. This means of tracking also allows TRM architects to potentially track the progression rate of standardized adapter solutions in OOR, an item of active discussion in the community.

Capturing Client & Servicer Needs

With this technology having a unique consideration of capturing both a product as well as a service that is needed (in the form of the technology), the authors elected to analyze and track the traceability of qualities needed, how the FOMs are informed, and which stakeholder needs are identified for the technology. This level of traceability allows us to ensure stakeholder requirements are met, that we properly capture the product-service relationship, and that the FOMs created harness executable and available data and metrics. The figure to the right displays these interactions and draws focus to some key considerations in the development of our FOMs for OOR:

- In a product-service-focused technology, client, servicer, and shared needs must be considered

- Metric traceability from client and servicer systems to FOMs (right side of figure) has the potential to concurrently root FOMs into two separate yet intertwined stakeholders

- Metric traceability from FOMs to identified stakeholder needs (left side of the figure) may increase confidence that stakeholder needs are captured, addressed, and traceable to quantifiable values

Applying this approach to OOR, we see that client-related items (blue), servicer-related items (green), and shared items (orange), can be easily traced to determine the inputs and outputs of each FOM. Having identified the metrics necessary to comprise each FOM and traced them to stakeholder needs, it was possible to generate mathematical models for each FOM. With these metrics founded in direct measurements from operations, engineering designs, or requiring introductory orbital mechanics calculations, the need to generate complex models to gather critical data was limited. To further validate this approach, traditional-focused FOMs (e.g. total kg fuel transferred) will be tracked in parallel with the proposed FOMs to inform a comparative view of the results. Next, the development of mathematical models and bounding of input variables for FOM modeling was necessary.

Capturing FOMs Mathematically

The table below shows units and nominal values that the authors propose to track the technology progression over time using engineering-based data. Upon searching available literature for the required data and direct FOMs, some were easily located, while others were limited in availability. Sources used to generate nominal values and value ranges are noted in the citation column, drawing attention to real-world missions or near-term prototypes. Of the selected FOMs, the Fuel Mass Ratio was easiest to quantify, while the Mean Refuel Rate proved to be the most difficult, with total refueling time for historic missions difficult to locate for multiple satellites. Even with this being the case, the authors will continue to explore this metric and attempt to capture more data in this area.

Example In-Depth Exploration of a FOM

To gather data, multiple online sources, including databases, news articles, FCC filings, and user manuals were used. Citations [5-43] were used to gather this data. The figure below (left) shows all unfiltered data found on satellite refuelers and related technology demonstrations for fuel-mass-ratios of refueling satellites. Mission dates range from 1978 to future missions in 2025. For satellites in the future, projected or advertised values were used to generate their fuel-mass-ratio values. It is also important to note that for three of the data points, calculations of fuel onboard were completed to gather the required data point. Due to the competitive landscape of on-orbit refueling, some companies limit the publicly available data to alternative metrics (e.g. lifetime extension time) that require calculation of fuel mass. These calculations were completed for the MEV-1 and MEP systems. For ease of viewing, a vertical dashed black line is included in the figures below to highlight the current day. Once the data was fully generated and plotted, a line-fit was applied to attempt to find a mathematical/quantitative rate of improvement. We see that in the left figure, a linear fit provided a mathematical prediction but is somewhat poor in overall fit with an R-squared value of 0.1 (with a third-order polynomial having an R-squared value of 0.4). To overcome this limitation, it was necessary to filter the data points to those that are most valid for the analysis.

When selecting which data points were valid, it was necessary to track which satellites were considered state-of-the-art while also having the sole intent of transferring maximal amounts of fuel. With some of the satellites developed as prototypes to prove specific aspects of refueling in orbit, they were not built with the intent of maximizing fuel transferred, as would be the case in a fully functioning system. To account for this, any satellite that was not focused on fuel transfer or advancing the state-of-the-art in refueling was removed from the analysis to provide a more accurate view of technology trending, as seen in the above right figure. Looking at the progression trend of the filtered data, we find that a third-order polynomial line fit is moderately effective at capturing the technology advancement, with an R-squared value of 0.78. This type of line fit also better informs where the technology is likely in its maturation phase. With the FOM stagnating from 1978 to the mid-2000’s, we see a notable increase in capability in the current day as well as the near-term projected future. Bounding this within the theoretical limit (discussed later), this leads us to believe that on-orbit refueling is in the innovators / early adopters phase of its lifecycle adoption, as covered in the class lecture (early lifecycle). Using a plot similar to those described in Lecture 7 (Technological Diffusion and Disruption), on the technology capability S-curve, we assert that on-orbit refueling is somewhere within the green box in the figure to the right. This point is characterized as the “takeoff” point in the technology s-curve, with incubation being extended over the previous 40-50 years of refueling efforts. The authors believe that OOR will soon enter the rapid progress stage if prototypes that are advertised are realized and made available.

The curve parameters are highlighted by a shallow increase in capability in its early lifecycle (during the first golden ages of space, later leading to MIR and the ISS), followed by a dramatic jump in capability that the authors believe current-day shows to be the initial stages of large capability jumps. Stagnation of the technology development is predicted to occur when vast improvements in OOR-centric technologies have been exhausted and advancements in tertiary sciences (e.g. materials science) occur, allowing subtle improvements to OOR satellite performance. With on-orbit refueling offering significant capabilities but also introducing significant risk to satellite systems, the authors believe there is a need to validate and test out OOR capabilities before they will be widely adopted. This phenomenon will likely result in a sharp technological improvement occurring priori to any advancement in the adoption rate of the technology. It is important to note that although this one FOM shows a steep increase in performance, other FOM preliminary results show somewhat similar advancement in trends.

The final aspect of the fuel-mass-ratio plots is the theoretical limit imposed by the system on the FOM. Considering that a higher fuel-mass ratio is better for the system, this value will likely continue to improve over time but is limited by the design of satellite systems. Advancements in material sciences can make satellite components smaller and/or lighter, but there will always be a need for satellite subsystems, including structures, fuel tanks, thrusters, communications systems, etc. These systems require a portion of the mass budget on a satellite system. To account for potential advancements in space systems and related materials sciences, this theoretical limit was placed at 95% of the satellite mass (meaning 95% of the satellite mass could be fuel). Any ratio beyond this is thought to be impossible due to the mass needs of the other satellite subsystems for a fully functioning refueling system.

Alignment of Strategic Drivers

To capture the interactions between the market/business objectives and the product-level FOMs, the development of a strategic driver table was completed and shown below. To hone the focus on prioritized items, the top three drivers were selected, which directly aligned with the technology roadmap and FOMs. The first and most important driver to date in the industry is the proof-of-concept and wider proliferation of commercial refueling in space. As seen in some of the previous plots, the action of refueling in space has been primarily a government function over the past four decades. To gain entry into the market space, the industry aims to establish success in refueling systems on orbit and do so multiple times while making a profit. The primary factor in this process is a compatible docking and mating system for customer and client systems. For this reason, an industry-standard docking/mating interface was chosen as the first commercial strategic driver. To support and connect this driver, the use of our mean-time-to-refuel FOM can track progress, anchored in a metric of transferring 4kg/hr of fuel to client systems when refueling. This metric was selected for its balance between previous refueling systems and anticipated future capabilities published by OOR companies.

For the second strategic driver, as one would expect with any organization, it is necessary to carry out OOR while also generating a profit for the company. With recent advancements in launch technology and supporting technologies, this is now possible. It is also important to capture the profit generation for the company while balancing the needs of customers. If prices charged to customers exceed the alternative of launching a new satellite, the decision calculus results in OOR companies losing business to launching spare or replacement satellites. Tying this driver to FOMs and technical metrics, we see that our cost/kg of fuel delivered FOM is a direct match for this relationship. To allow profit generation while technology continues to evolve, the authors elected for a pricepoint goal of <100k/kg of fuel delivered, with a reach goal of <$50k/kg. These metrics were chosen for their balance of maintaining profit while also stressing the technical capabilities and development/manufacturing methodologies of refueling satellites. As the technology matures, the building of satellites should grow cheaper, allowing more breathing room for companies in regard to prices charged to customers for fuel. The end state of this development is a competitive approach similar to current fuel sources and providers on Earth.

The third strategic driver is one that benefits not only OOR providers but also the clients. The ability to maneuver freely and with less restraint has been a need for satellite systems for years. To counterbalance this, developing a system that allows OOR satellites to maneuver to multiple customers without greatly sacrificing their business case is an item of great interest. To achieve this goal and relate it to our FOMs, we see that the fuel-mass-ratio of satellites is a direct connection. As the mass ratio of a satellite increases, so does the fuel on board and the inherent ability to maneuver or transfer more fuel. Considering this metric, the authors elected for a target of 0.75 or 75% fuel-mass-ratio for dedicated refueling satellites. This ratio provides ample fuel for maneuvering and refueling while also not imposing unrealistic constraints on the mass of satellite primary support systems (ex., satellite bus, power system, comms, etc.). Through the use and alignment of these three strategic drivers and targets, we are able to guide our roadmap and track the progress of achieving industry-wide goals.

Positioning: Company vs Competition (FOM Plots)

To look at the positioning and competitive benefit of differing approaches to OOR, it is helpful to analyze the positioning of companies vs. each other. An effective means of accomplishing this is to see where different companies are represented on our FOM plots. Upon deeper analysis of the FOMs selected, the two most informative ones were refueling $/kg and fuel-mass-ratio of servicing satellites. These FOMs had statistically relevant and supportive data available for use while also showing trending that is helpful to determine the progression of the technology as a whole. Although the last two FOMs (% customer lifetime extension and mean refuel rate) are believed to be effective metrics, they are excluded here due to proprietary data limitations. As OOR technologies evolve, the authors believe this constraint will be lifted, increasing the value of these two FOMs.

Price per KG of Fuel Delivered ($/kg)

Focusing our first comparison on the price per kg of fuel delivered to customer satellites, prices advertised by commercial assets and overall program costs for government programs were used for financial figures. When looking at the ability to provide fuel to space assets, the capability is not limited to commercial programs, with government organizations having a heritage in the discipline. Efforts include the Mir space station, ISS, and government prototypes including the DARPA/NASA orbital express mission and OSAM-1 mission. Although beneficial in consideration as a refueling mission, it was discovered that inclusion of space station data for this metric was ill-advised if not accounting for costs associated with human support of refueling operations. With space station refueling often involving human operations to transfer the fuel and being based on an established processes that are not directly translatable to autonomous and robotic-focused systems, fuel costs for these scenarios were found to be exceedingly cheaper than alternatives. This phenomenon is highlighted by the red data points seen below in the $/kg plot for OOR systems. To rectify this bias in data, systems that refueled the space station were included in the plot in red and then included capturing a factor of the ISS and astronaut costs for availability (seen as black points). All items included in the equation trending are shown as black points. Looking at this plot, there are multiple interesting points of emphasis.

- Although the line fit has a relatively high factor (~0.93), the products/solutions currently on the market are notably above or below the trend line, with most outside the shaded +/- $500k/kg region. This is likely accounted for by two factors: (1) the intent of each mission and (2) the logistical approach of singular or multiple (depot) servicer satellites in each unit. Analyzing the intent of these missions, OSAM-1 is a multi-purpose mission, with refueling only being one of many intended purposes of the prototype. Otter Pup is similar in this capacity, with it being a pure prototype mission that is more closely aligned with a proof of concept. Alternatively, MEV 1, 2, and Tanker 02 are single satellite systems designed for operational use on client systems. Considering the MEP system, this concept is planned to harness a “depot” approach, where smaller satellites will dock with a larger one, which the authors believe has a direct impact on the overall $/kg metric. Although it is displayed as a negative consequence in this area, it injects flexibility in the refueling design that should not be overshadowed.

- The trending of systems appears to be aligned with an exponential decay in $/kg, approaching the theoretical limit in out-years. The authors anticipate this will be bounded further by advancements in satellite technology and necessary profit margins for companies. Future data points are noted with the * in the table. Additionally, new-start companies offering first-of-kind refueling and repositioning services are likely offering them at a competitive price point to gain interest in the capability across the space enterprise.

- Using astronauts to augment refueling options can provide a dramatically reduced cost for the system but is an unfair bias as the current metrics do not account for the price penalty to have astronauts available for use and support.

Presenting the data for the points within the plot, we are also able to discern the current stakeholders and companies producing OOR systems. Attention is drawn to the current uptick in interest, especially from commercial stakeholders. An additional topic of interest is the fuel-mass-ratio of satellites, which is covered later as the second FOM analyzed in detail. A notable limitation to this FOM analysis is data availability. The above figures were gathered from online sources that furnished necessary metrics. To enhance the impact this FOM has in comparison, metrics for other OOR systems that are used in the other FOMs would be of immense value to drawing direct comparisons for companies in the OOR enterprise in the future.

Fuel-Mass-Ratio (%)

Transitioning the analysis to the second FOM, fuel-mass-ratio of servicer satellites, we see a similar timing trend of missions over the past five decades. Starting with early Progress missions to MIR and then later the ISS, fuel mass ratios have seen a unique technological evolution. Unlike the $/kg FOM, with fuel-mass-ratios of refueling satellites not being heavily influenced by astronaut/autonomy considerations, these data points were included in this analysis. It is of note that omission of space station metrics (for consistency) was considered but did not have a large impact on the modeling and trending of the system. Also of note and mentioned previously, the plot shown below focuses on data that is considered state of the art in OOR, and does not include systems that are introductory or focused on specific aspects of OOR but not intended to provide service as a full capability (ex. experiments of OOR subcomponents). Looking at this plot, there are multiple interesting points of emphasis.

- The use of two separate trendlines help us to bound the expected growth of. the technology, with the blue line being a slow and conservative growth of the tech, starting at 0. The orange line is a more aggressive and optimistic growth pattern of the technology, starting at 20% and growing faster to the theoretical limit. The reality of the technology growth is believed to fall within the two plots in the future.

- With trendlines have relatively high R2 factors (~0.77 & 0.62), similar to that of FOM1, this metric shows strong proximity to the trending with more data points considered.

- Accounting of dedicated refueling missions and multi-purpose mission should be tracked to ensure that biases are not injected into the FOM trending analysis. As OOR systems become more prevalent, the authors suggest either breaking this plot into two separate analyses of dedicated refueling and multi-purpose missions or capturing only the applicable refueling portions of multi-purpose systems if they are easily partitioned/modular.

- A notable stagnation of OOR technology is seen in the 1985-2010 region, which lends itself to many interesting questions. Although beyond the scope of this roadmap, consideration of space launch access prices and space policy could shed light on the exit of this stagnation period.

- The notable uptick in fuel-mass-ratios seen in current-day systems is promising, but the jump for future systems should be considered cautiously. With all of the predictive cases based upon company press releases and/or anticipated performance figures, they are not yet confirmed, with some having higher confidence in accuracy than others.

- Looking at the plot from a 1st order perspective, the technology trending appears to be following an anticipated S-curve trend. This can be helpful in predicting and validating future system designs and they are brought to the market. Covered later in the technical model of the system, the mass (and inherent technological level) of refueling satellite subsystems (ex. power, comms, bus, etc.) will directly impact the theoretical limit of this FOM.

Presenting the data for the points within the plot, we are also able to discern the current stakeholders and companies producing OOR systems. A focus area of this data is the jump to a 50% mass ratio for refueling satellite systems. This increase increases prototype performance in this FOM, even beyond that used for space station missions. Although the same reservation for future-oriented data is suggested for this FOM, the recent jump in performance and its validation of an S-curve for the technology not only in the commercial sector but in government missions as well. A revisit of this data within a 3-year period is suggested by the authors to validate the trending of the FOM further.

Percent Customer Lifetime Extension (%) & Mean Refuel Rate (kg/hr)

Although these two FOMs are value-added in aligning client and servicer needs, capturing client-servicer dependencies, and tracking the overall technology trending of OOR systems, a lack of available and non-proprietary data limited the generation of these FOM plots. If less than five datapoints were able to be found for each plot, they were omitted from this analysis. This omission highlights a future opportunity for this roadmap to be run as this data grows more available and distributed to the community. As a means to augmenting this data, the authors are currently exploring analogous terrestrial-based cases that could provide comparable mathematical trending patterns for consideration.

Vector Chart

To aid in the discussion of how the community and specific companies/organizations have progressed the state-of-the-art in OOR systems, a vector chart is shown below. This approach to visually displaying company progression highlights system and specific technology advancements and their impact on the system's value for the producer and the customer. To facilitate a balanced analysis, the DARPA Orbital ExpressOOR system was selected as the reference/baseline product for comparison.

Orbital Express was selected as the reference product because it was one of the first successful unmanned OOR systems fielded.

Looking closely at the vector chart, we see that the space station-focused systems (Progress & ESA) added great value to the customer but struggled to do the same for the producer (besides profit). With these systems focused on a very specific application, their impact on the broader community is/was very limited. Looking at other government programs, the OSAM-1 future mission is anticipated to add greater value to both the customer and producer by validating new capabilities while also refueling a satellite system that is analogous to many other traditional satellites on orbit. Other systems already fielded in the commercial sector include Orbit Fab’s Tanker 01 and Northrop Grumman’s MEV (1 & 2) systems. These technologies added great value to the community and customer by validating a means of testing a “standardized” refueling valve system and repositioning satellites via a dock-and-maneuver approach (Tanker 01 and MEV, respectively). Iterations on these technologies and noted improvement will further increase the value provided to both the customer and producer, with Northrop Grumman developing their MEP system and Orbit Fab working towards deploying their Tanker 02 prototype. This list of OOR technologies is not all-inclusive and is only intended to show the value impacts in the community when looking at widely publicized OOR systems. Additions and expansion of this vector chart is a topic of future work that the authors note as an iterative effort.

Technical Model (Modeling and Sensitivity of FOMs 1 & 2)

Morphologial Matrix & Tradespace

An effective means of capturing the available tradespace for a technology is the use of a morphological matrix. To this end, this matrix was generated for OOR technologies and capabilities and is shown below. To give a better scope of real-world systems within this matrix, example OOR systems are provided with color coding to show what approaches are currently used or are planned for use in the near-term future.

Viewing the OOR morphologic al matrix, we see that although trends have been established for the past, there are some deviations from that moving into the future. Looking at the tradepsace that this enables, different orbital regimes, fuel types, launch vehicle solutions, and expected refueled lifetimes are a few of the aspects that OOR producers can consider when developing and maturing systems.

Technical Models of FOMs

To support the analysis of OOR technologies, mathematical models and regression equations based on available data were used to determine the sensitivity of variables under consideration. With ATRA harnessing a FOM-based analysis methodology, it was deemed most applicable to provide models of the two most impactful FOMs to provide traceability.

FOM (1) [cost/kg]

The first FOM modeled was cost/kg of fuel delivered on orbit:

Although this equation seems dangerously simple, consideration must be taken into what components comprise the total cost of a system and how much mass is transferred. These considerations shed light on the inherently complicated nature of this model. Focusing on the cost portion of the equation, it is comprised of four major factors, with the rest abstracted due to their believed minimal impact:

- Servicer satellite development and manufacturing cost (c_dev)

- Space access (launch) cost (c_launch)

- Servicer satellite operations cost (c_ops)

- Profit margin for the servicing company per mission (c_profit)

Satellite development and manufacturing cost (c_dev):

When attempting to determine the potential cost of developing and manufacturing a satellite, the two most common, well-established, and widely accepted practices include top-down and bottom-up analyses. Top-down analyses are typically parametric-based and harness a comparative approach to similar or analogous systems [50]. Bottom-up approaches take a summing approach, breaking a system into its components and adding them to generate a cost figure [50]. With top-down approaches heavily used in the initial phases of programs, that method was selected for use in this model. An added advantage to this approach is that it can harness satellite mass as a primary variable and close proxy for overall cost. Using the NASA JPL cost model [51] for small satellites as a foundation, notable alterations were made to the equation to account for differences in intended use. With the JPL model accounting for satellites that use large scientific payloads that are cutting edge, the cost model was biased towards more expensive one-off solutions. To align the algorithm with satellites that are much more simplistic and will be built on a production scale, a 10% factor of this equation was implemented. This alteration was also made to capture the large mass ratios of the satellite being fuel, which was not the case for the JPL model. These alterations resulted in the following equation:

To validate this algorithm, a real-world and current use case was considered with the Orbit Fab Tanker system. This analysis result, when included in our overall model, produced values within 10% error of the advertised pricing.

Space access (launch) cost (c_launch):

Advancements in launch vehicle (LV) technology, especially in the commercial domain, have been plentiful over the past two decades. With these advancements, reduction in launch cost and the introduction of LV options (ex. small, medium, and large LVs) have arisen. To capture this change in space access, the authors harnessed publicly available data to determine the cost of currently available LV solutions. For large LVs, cost metrics for the most common solution (Falcon 9 B5) were gathered and used to produce an expected value per/kg of payload. For medium and small LVs, the market space is much smaller, which lent itself to using a metric from an established/near-established provider in each area (Firefly and RocketLab, respectively) to generate similar metrics for cost/kg of payload. To capture the complication of rideshare (the sharing of available payload mass and space on launch vehicles) associated with the LV community, an algorithmic approach was harnessed that uses a ratio of the launch vehicle and cost/kg price. This approach equates to only paying for the mass portion of the LV that is used by the OOR payload. A notable assumption of this approach is that another customer purchases the remainder of the LV available mass. Looking at the medium and small LV options seen in the table below, cost/kg prices were found to be multiple times more expensive than the large LV solution. With this consideration and the limitation of medium and small LVs only being able to reach LEO orbits, the authors elected to use the advertised Falcon 9 B5 cost metrics for launch cost calculation for both LEO and GEO cases. The resulting equations that were used for launch vehicle cost include:

Servicer satellite operations cost (c_ops):

Due to the foundational principles and technologies used to communicate with and control satellite systems, although there are some differences in these approaches when comparing LEO and GEO satellite systems, they are considered negligible in the context of this analysis. As such, a flat rate cost is assumed for all satellite operations of an OOR system per year of operation. With a value of $1M (FY22$) produced from within the range of expected satellite operations costs, it was used for this portion of the calculation.

Profit margin for the servicing company per satellite (c_profit):

To ensure that the costing of the system accounts for the necessary profit margins for the company, a flat rate of 10% profit margin beyond the otherwise totaled costs of the system was used when determining the overall cost of the system. Displayed in equation form, this approach equates to:

Last, the capture of the second half of the primary equation, the mass that is transferred to the client satellite, comprises the denominator of our cost/kg FOM. To generate this value, the fuel-mass-ratio was considered in line with the overall mass of the satellite. With this having a wind variance in historical context, this was considered for the analysis. The mathematical calculation for the mass transferred resulted in the equation:

Combining all of these equations, we are able to formulate a final equation for analysis. Due to the length of the c_proft portion of the equation, that is represented as that variable in the below equation, still using the derivation shown above. Of note, this equation is for the LEO case. For the use of the equation for the GEO case, the second top term for launch cost needs to be changed to 8070 instead of 3045. That version of the equation is omitted for the sake of brevity.

By gathering baseline metrics for this equation and analyzing the model through a partial derivative difference method, we are able to determine the impact that a 1% change in each primary variable has on the overall FOM. To inform this process, the partial derivatives of FOM 1 were taken, and are shown below.

Using these derivatives, a sensitivity analysis was completed. This is powerful as it can educate stakeholders as to which aspects of a design are most important to invest resources into advancing, or stated otherwise, where your potential best “bang for your buck” is. This process was completed in addition to a Monte Carlo analysis. With the Monte Carlo results currently beyond the scope of this analysis, they are omitted here but can be provided upon request. To visually display this information, normalized sensitivity graphs in the form of tornado plots were produced. For comparison, plots were created for both LEO and GEO orbit cases. A side-by-side of these results is shown here, with interesting results.

Looking at the first sensitivity plot of the LEO use case, we see that for a 1% change in each variable, the fuel mass ratio variable is the most sensitive to impacting the FOM. For this FOM, a lower value is better for the customer, resulting in the fuel mass ratio being the strongest (by far) variable in reducing the cost/kg of fuel on orbit. Profit margin, satellite mass, and ops lifetime have much smaller impacts, and all increase the cost of fuel on orbit. This factor is important to note for OOR developers as they progress the technology, with the fuel mass ratio having an almost 1-to-1 relationship (normalized) with the FOM performance. Next, we look at this same FOM in the GEO use case. Similar to the LEO case, the GEO application of this FOM has the same ranking of sensitivity of the variables, but now with the fuel mass ratio even more important, having a greater than 1-to-1 relationship with the FOM. The emphasizes the importance of OOR satellite fuel mass ratios for servicing in GEO and should be considered when developing and manufacturing OOR technologies.

FOM (2) [fuel mass ratio]

The second FOM modeled was the fuel mass ratio of OOR servicing satellites:

Similar to FOM 1, this equation seems relatively simple but has a layered complexity that requires exploration to determine the impact and sensitivity of variables. First, we look at how we calculate the mass of the fuel on board. Using fundamental equations for the density of a liquid and the area of a sphere, we find the equation form of the numerator to be:

An important assumption for this approach is that the fuel tank used within the system is spherical, with r in the equation above being the radius of the tank. Upon searching satellite fuel tank systems and anticipated OOR systems, this assumption was found to be reasonable, especially for a first-order analysis. For the fuel densities of fuel, open-source values for typical space fuels (assumed liquid form) were gathered and are shown in the table below. With the mass of the fuel characterized, it was necessary to capture the elements that compose the total mass of the satellite. Breaking this down into its constituent components, we find:

Within the equation above, t represents the thickness of the tank, and the density of the fuel tank material used was that of titanium, the most common material used for satellite fuel containers/tanks. For the mass of the subcomponents, analogous values were found and used for the base case when attempting to model the system. With all of these variables combined, a holistic equation for the FOM was found to be:

Taking this equation and applying the same method used for FOM 1, a partial derivative difference analysis was completed. The resulting partial derivatives fro FOM 2 (f2) include:

Taking reference metrics and inputting them into the model allowed the creation of sensitivity plots from these partial derivatives for both LEO and GEO use cases, seen below.

Notably, different from FOM 1, the fuel mass ratio has multiple impactful variables for the LEO use case. Although these variables have a lower impact (<1%) than FOM 1, we see that the radius of our fuel tank, the density of the fuel selected, and the inherent volume of the tank have the biggest impact on our FOM. With a higher value representing a better solution, we find that increases in fuel density and tank volume and decreases in the mass of the tank (via thickness and density) and the mass of subsystems benefit our technical performance. Looking at this analysis for the GEO case, we see that there are minimal changes to the sensitivity metrics, which informs us that the GEO and LEO use cases themselves have little impact on the fuel mass ratio FOM. This is notable, as the opposite was found when looking at the cost/kg values for FOM 1.

Key Publications & Patents

When attempting to capture the current “lay-of-the-land” regarding OOR, it is necessary to research and capture key publications that have contributed to the development and maturation of the technology. To that end, this section discusses key publications (both historical and current), as we all # patents, that the authors believe to be fundamental and impactful in the continued improvement of OOR technologies and capabilities.

Publications

- 1. National In-Space Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing Plan / In-Space Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing National Strategy [44,45]

- Author(s): Ezinne Uzo-Okoro et al.

- Published: White House website, 2022

- Summary: Somewhat unique to this technology, the US executive branch (through the ISAM interagency working group) published a national strategy and implementation plan for the broader scientific area of in-space servicing, assembly, and manufacturing (ISAM). With OOR being a subcomponent of ISAM, it is also captured in this plan. This publication is powerful as it provides an overarching plan to guide developmental and policy decisions for OOR technologies. Specific organizations and their role in developing space servicing technologies, overarching areas of interest, and prioritized efforts are laid out in these documents. This information is informative to this roadmap as it increases confidence in the anticipated path forward by discerning where resources are planned for use and where responsibility lies for differing groups in the path to advance OOR/space servicing technologies.

- 2. ISO 24330:2022(en) Space systems – Rendezvous and Proximity Operations (RPO) and On Orbit Servicing (OOS) – Programmatic principles and practices [46]

- Author(s): ISO 2022

- Published: ISO website, 2022

- Summary: With rendezvous and proximity operations (RPO) being a crucial capability in the operational chain of providing OOR, efficiently and effectively carrying out RPO is critical to OOR success and development. Directly related to refueling time and compatibility, this information impacts multiple FOMs highlighted in previous work. With this publication providing an international standard by which OOR should perform RPO, developers and technology innovators can build towards a common goal/standard when advancing OOR tech. This is a critical idea as it enables the compatibility of satellite systems in the OOR client-servicer relationship.

- 3. RAFTI(TM) User Guide, Refuelable Spacecraft Requirements Specification [47]

- Author(s): Emily Kolenbrander, Orbit Fab 2022

- Published: Orbit Fab website, 2022

- Summary: The referenced user manual is a powerful publication in that it provides a realized and widely adopted interface for physical fuel transfer that is growing exceedingly common in the OOR industry. Just as in the other publications, this standard is powerful as it enables OOR companies and/or customer satellites to build towards this standard with known engineering parameters. This publication is also powerful as it covers aspects of CONOPS, volumetric constraints around the valve, physical limitations of docking, fluid flow rates, mass allocation, and notional refueling architectures.

- 4. On-orbit service (OOS) of spacecraft: A review of engineering developments [48]

- Author(s): Wei-Jie Li et al.

- Published: Aerospace Sciences, 2019

- Summary: A foundational element of advancing OOR technology is understanding what advancements have been made in the field in the past and how they can benefit the This publication provides a thorough background of prototype missions and engineering advances made in the OOR field up to 2019, is heavily cited (221 times to date), and looks at missions from around the globe to provide an enterprise-wide perspective. This publication provides an easily accessed and usable document for OOR developers to reference for engineering designs, inspiration, and items to avoid that have been tried in the past.

- 5. Versatile On-Orbit Servicing Mission Design in Geosynchronous Earth Orbit [49]

- Author(s): Jennifer S. Hudson and Daniel Kolosa

- Published: Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, 2020

- Summary: With the architectural designs of OOR systems having a wide tradespace ranging from a singular satellite to multiple disaggregated satellites that use a fuel depot system, a proper understanding of the pros and cons of each approach from an orbital mechanics, engineering, and profitability perspective is crucial. The referenced publication analyzes the potential for GEO servicing from a multifaceted perspective, including refueling. This article helps OOR tech developers design systems that can maximize fuel transferred to customers while also maximizing the profit that can be gained as a service.

A notable trend in the on-orbit refueling and repositioning enterprise is a dramatic increase in interest and publications on the topic. To capture this trend, an analysis of the number of publications per year was gathered via the use of Google Scholar. As seen in the below figure, interest has ebbed and flowed over the decades, with it increasing consistently since the early 2000’s and seeing a dramatic jump in 2017. Although beyond the scope of this analysis, the authors believe this jump to be accredited to not only engineering advances but also space policy and commercial business developments.

Patents

Transitioning to patents that have impacted the design and development of OOR technology, multiple recent and historic patents are of note. Via the use of the US Patent Office website, the following patents were identified:

- 1. Systems and Methods for Creating and Automating an Enclosed Volume with a Flexible Fuel Tank and Propellant Metering for Machine Operations

- Inventor(s): Danial Faber et al.

- Assignee: Orbit Fab, Inc., 2023

- Patent #: US 11,673,465 B2

- CPC: B64G 2001/224; B64G 1/646; B64G 1/402; B64G 1/22; B64G 2004/005; (Cont.)

- Date: 13 June 2023

- Summary: This patent highlights the use of a flexible fuel tank design to moderate the use and transfer of fluids. This design has a stowed and deployed approach, where it can expand and contract to fit the needs of the satellite system. From a future-looking perspective, this patient could be influential in the design and use of OOR satellite systems as well as client satellite fuel tank systems. With tank material density directly impacting one of our FOMs, a change in this metric while sustaining the ability to transfer fuel would be highly advantageous to OOR systems. This approach also introduces a potentially new method of sustaining pressure inside fuel tanks and is an item to track as a potential disruptor in the OOR enterprise.

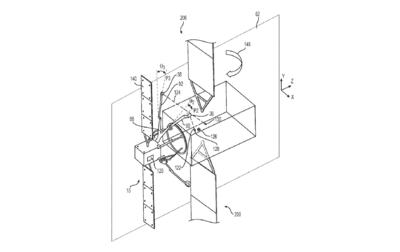

- 2. Service Satellite for Providing In-Orbit Services Using Variable Thruster Control

- Inventor(s): Michael Reitman et al.

- Assignee: Effective Space Solutions Ltd., 2018

- Patent #: US 20180251240 A1

- CPC: B64G 1/078 (2013.01); B64G 1/646 (2013.01); B64G 1/40(2013.01)

- Date: 6 September 2018

- Summary: When looking at how to reposition a satellite system, consideration of grabbing/latching mechanisms, interfaces, and thrust controlling must be considered. The above patent proposes a design that uses the variable thrust of a servicer satellite to control a client satellite (once docked/mated). The approach of gripping a satellite vs. using a traditional docking approach is a novel method of providing repositioning (space tug) services for client systems. This patent is powerful as it is directly related to some of the adopted approaches to repositioning satellites that are on orbit and require orbital maintenance. This approach is also powerful in reducing the risk of transferring fluids, as it eliminates that need by gripping and, in essence, becoming part of the client satellite. Once grabbed, the servicer satellite can thrust using its own propellant.

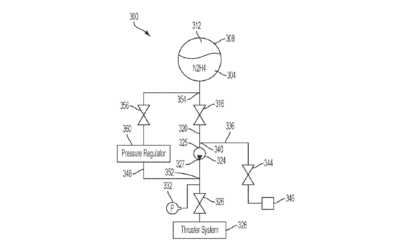

- 3. Active On Orbit Fluid Propellant Management and Refueling Systems and Methods

- Inventor(s): Gordon Wu et al.

- Assignee: Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. 2022

- Patent #: US 20220355954 A1

- Date: 10 November 2022

- Summary: The design and interoperability of OOR systems, fuel storage, and transfer processes are critical components to successfully refueling satellites. To transfer chemical fuel, the above patent highlights a single and multi-tank system that stores and pumps fuel from one system to another, highlighting a refueling intent. This patent harnesses an approach where the propellant is not pressurized by another gas, which is relatively novel in the community. By controlling the pressure that propellants are provided to tanks and propulsion systems, fuel can be transported and used for differing situations. This technology has a direct impact on the mass of refueling systems, which impacts two of the roadmap FOMs. This alternative approach to storing and transferring fuel could benefit refueling systems in the future and will be tracked to capture the impact on the community.

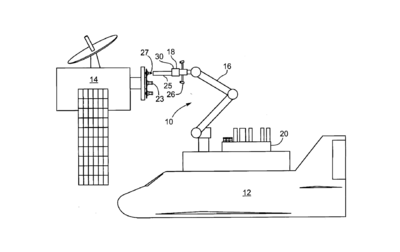

- 4. Satellite Refueling System and Method

- Inventor(s): Lawrence Gryniewski and Derry Crymble

- Assignee: MacDonald Dettwiler and Associates Corp., 2022

- Patent #: US 20080237400 A1

- CPC: B64G 1/22; B64D 39/06; B65B 57/06; B64G 1/64 (All 2006.01)

- Date: 2 October 2008

- Summary: Arguably, one of the foundational documents for current-day on-orbit refueling, the above patent lays out a methodology and system of applying robotic refueling for a satellite system from either a direct-earth launched satellite or a “mother” spacecraft in the form of a depot. This design is notably under teleoperation from a “remote” user, which could be on earth or at another location. Related aspects and inspirations for designs on current OOR systems can be seen from this patent, with systems such as OSAM-1 harnessing similar but not identical approaches to servicing and refueling satellites. With an expiration date of 2030, this patent has the potential to continue shaping how OOR is developed, matured, and carried out.

Research & Development (R&D) Projects

Continuing the forward-looking trend of this roadmap, it is next beneficial to look at R&D projects that could benefit OOR technologies. With there being two differing approaches to this methodology (1) gathering existing R&D projects and (2) formulating potential future R&D projects related to this roadmap to optimize maturation, the authors elected to perform (1). This approach was selected due to the optimal timing and development of R&D projects and to attempt to capture some of the tertiary benefits to OOR that the community is already in the process of expanding. To capture this information, an R&D portfolio framework diagram was created that tracks efforts and categorizes them based on process and product changes, as seen below.

There are some notable takeaways from this plot and the associated table on the right. First, we see that there is a wide spread of type of projects, ranging from R&D to platform basis. This further highlights the rapid expansion and interest in OOR technologies. We also see that there are notable process and product changes underway. Refueling valves, repositioning vs refueling, and means of grappling systems are some examples of these changes. These further emphasize the somewhat nebulous nature of OOR in its current state and the push to implement forms of standardization and expectations for the technology. To further educate the conversation, in-depth explanations of the listed technologies are shown below. Please note that this is not an all-inclusive list, only highlighting the prevalent and more well-known systems currently being researched and developed. The authors also note that this section is one that should be revisited on a regular basis to capture success and failures in the listed efforts, as well as any new notable and related efforts.

Financial Model

Model Overview:

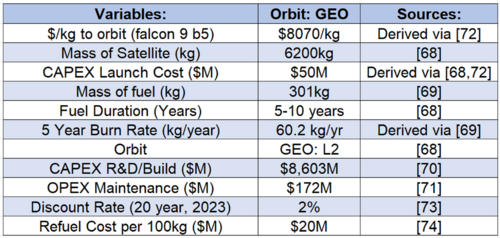

A financial model incorporating Monte Carlo simulation and Real Options Theory was derived from data primarily from the James Webb Space Telescope project, SpaceX Falcon 9, and Orbit Fab commercial refueling. While James Webb did not launch via Falcon 9 and is not compatible with Orbit Fab’s RAFTI refueling interface, the programs provide historical data for the model to simulate the impact of designing flexibility into a satellite in geostationary orbit (GEO). Since government satellites are non-commercial, the NPV of the model will be negative so the financial figure of merit is total cost per operating year [$M/opyr] to apply to both the commercial and non-commercial sector. The total cost per operating year is a function of cost over time, specifically, the sum of the capital expenditures (CAPEX) and operational expenditures (OPEX), divided by the years of operation. The model starts with a deterministic case of 5 years of operation, then incorporates uncertainty in the form of fuel consumption, and finally incorporates Real Options for on-orbit refueling.

The model incorporates several assumptions as detailed in Table [4-1] which include a 2% federal discount rate, an initial fuel duration between 5-10 years, and Orbit Fab refueling costs of $20 million per 100 kilograms of fuel.

Deterministic Model:

The initial, deterministic model was run using a 5-year mission duration, the low-end mission duration target for the James Webb Space Telescope. The model yielded a Net Present Value of -$7.72 billion for the project which comes to a cost of $1.54 billion per operating year of the satellite.

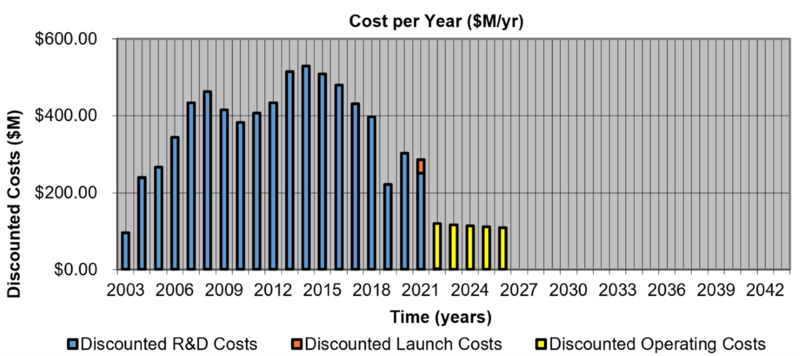

Model with Uncertainty:

The model was updated to include uncertainty of the satellite’s fuel consumption rate. Since the James Web Space Telescope was launched with a mission window between five and ten years, the fuel consumption per year was adjusted to fall within a burn rate of 30.1kg/year (10-year mission) and 60.2 kg/year (5-year mission). A 2,000-run Monte Carlo simulation was then conducted to model the impacts of fuel consumption uncertainty on project NPV and cost per operating year. The resulting average NPV was -$7.87 billion which equates to a cost of about $1.13 billion per operating year of the satellite.

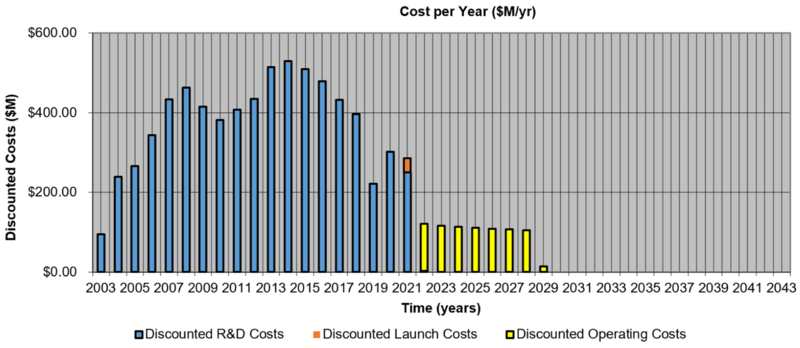

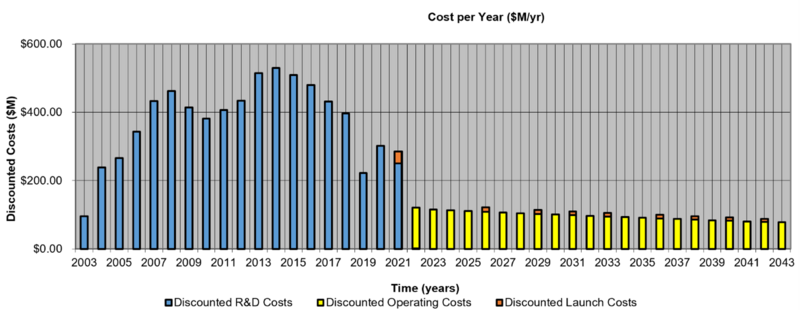

Model with Real Options:

To incorporate flexibility of on-orbit refueling or repositioning (OOR), the uncertainty model was updated to simulate the satellite receiving additional fuel in 100 kilogram increments. The hypothetical client satellite would have the real option of docking a refueling satellite in order to extend the operational life of the client satellite. The option could be exercised if the managing team desired more operational time at the price point to refuel. The price point was assumed to be the commercially advertised price by Orbit Fab of $20 million per 100 kilograms of fuel [74]. Additionally, the production cost of a refueling interface was assumed to be negligible and absorbed within the existing R&D cost. Regarding time horizons, it was assumed that the managing team would desire to operate the satellite as long as possible until 2043, or 40 years after the start of the R&D process. This model did not factor uncertainty of component failure or disruptive technological innovation that would render the satellite inoperable or obsolete. The model assumed that the satellite remained healthy and mission viable until 2043.

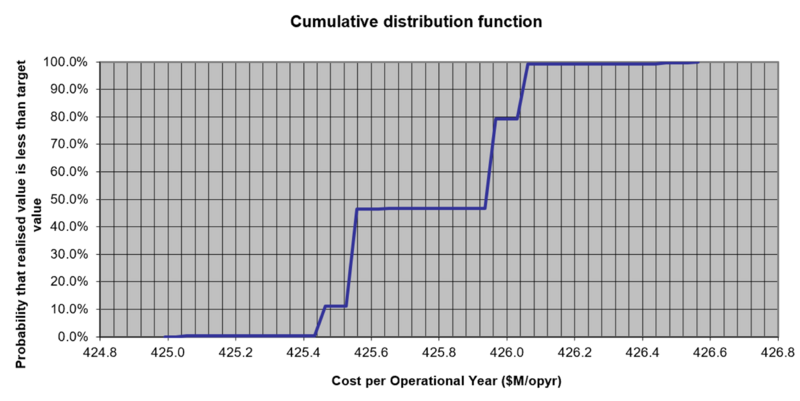

The flexibility in designing a refueling capability provides significant upsides in both the operational duration and cost per operational year. A 2,000-run Monte Carlo simulation was conducted resulting in an average NPV of the real options model of about -$9.37 billion. The increase in operational timeframe significantly decreased the average cost per operational year to about $426 million with a standard deviation of $0.4 million.

Assuming a low CAPEX for a refueling interface compared to the overall satellite R&D expenditure, purchasing the option of on orbit refueling shows significant upsides. For this financial model, OOR shows a 60% reduction in cost per operational year due to mission extension. Additionally, a longer mission would mean more earnings for commercial spacecraft or more scientific value for institutions such as NASA.

Technology Strategy Statement

Coming full circle with this roadmap, we see that there have been ample advancements in the field of OOR. Traceability and dependencies between OOR system and subsystem forms, functions, and flows of capabilities were generated through the use of DSM and OPM diagrams. Figures of Merit were established that allowed users to track the technology progression from a technical and monetary perspective. Strategic drivers were next generated to ensure that company goals were aligned with enterprise-level technical targets, allowing us to compare company performance with the competition. To expand our technical understanding of the science, a technical model was generated that showed physical dependencies of the FOMs and a financial model that showed the potential profitability of the technology over time. To complete our knowledge of OOR, we also looked at notable patents, publications, prototypes, and R&D projects that have the potential to impact the OOR enterprise.

Using this gathered knowledge, we can conclude our roadmap with suggestions and targets for future maturation and development of OOR technologies. These targets are intended to stitch together resource allocation considerations, figure of merit goals, and an overall vision of the technologies use and impact on the community.

Background Image Credit: U.S. Space Force and Astroscale to co-invest in a refueling satellite - SpaceNews. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2023, from https://spacenews.com/u-s-space-force-and-astroscale-to-co-invest-in-a-refueling-satellite/

- Now (2023):

- Near-term investment of resources into standardized interfaces for refueling and repositioning, grappling approaches to maneuver satellites without imposing damage while allowing separation, and tailorable approaches to refueling legacy systems (those not planned for refueling) as well as new-age satellites (those planning for refueling) will greatly improve the effectivity and efficiency of OOR. R&D in this area can directly support the advancements of mean refueling time and percent customer lifetime extension FOMs.

- 2025:

- Continued focus on improving refueling/repositioning satellite fuel-mass ratios (as a FOM and technical metric) is likely to occur, with refueling companies' profitability and lifetime extension benefits for client systems directly associated with the metric. Advances in materials sciences, fuel tank systems, subcomponent mass properties, heavy-lift launch vehicles, and potentially disaggregated systems (ex., depot approaches to refueling) are likely to occur within the next 3-5 years and will have a direct impact on fuel-mass-ratio and cost/kg metrics.

- 2027:

- Use of the developed technologies and advancements in OOR have the potential to enable a profitable business case for OOR services, expanding the market demand away from mostly government clients and to a higher ratio of commercial client needs. This transition will directly impact the cost/kg FOM and potentially increase the market interest in advancing OOR-related technologies.

- 2030:

- Current R&D-focused efforts, including gecko-inspired robotics and soft robotics, will potentially bear fruit within 7-10 years, allowing OOR to be completed more efficiently. These advancements impact the mean refuel time FOM and expand the potential use of OOR to support other large initiatives, including orbital debris mitigation and limitation. This aspect of OOR use is a potential paradigm shift that should be tracked in future roadmap iterations.

- 2035+:

- Harnessing the combined targets and capabilities, the vision for OOR in the 2035+ timeline is that it will be widely proliferated in space systems. The broad use of OOR will enable a fundamental shift in space operations, risk adoption, satellite system lifetime, and accessibility. This impact is anticipated to reach beyond LEO, influencing space systems in GEO, the lunar realm, and beyond.

As is the case with every technology roadmap, the authors suggest that this document be revisited on a regular basis to ensure accuracy with changing times and data/metrics, applicability to the community, and alignment with any changing policy or directives related to OOR use.

References

[1] Orbit Fab | Spacecraft Refueling. (n.d.). Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://www.orbitfab.com/

[2] Refuel in Orbit, 22,000 Miles Above Earth, with Orbit Fab Gas Stations. (n.d.). Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/refuel-orbit-22000-miles-above-earth-fab-gas-stations-christopher-u-

[3] GPS Block IIF – Spacecraft & Satellites. (n.d.). Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://spaceflight101.com/spacecraft/gps-block-iif/

[4] Robotic Refueling Mission | NASA’s Exploration & In-space Services. (n.d.). Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://nexis.gsfc.nasa.gov/robotic_refueling_mission.html

- Citations [5] - [43] were used to gather the required data for the FOM trending plot

[5] Hall, Rex D.; Shayler, David J. (2003). Soyuz: A Universal Spacecraft. Springer-Praxis. p. 272. ISBN 1-85233-657-9

[6] Progress 1 - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progress_1

[7] 35 Years Ago: STS-41G – A Flight of Many Firsts - NASA. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.nasa.gov/history/35-years-ago-sts-41g-a-flight-of-many-firsts/

[8] Orbital Refueling System (ORS) - Google Books. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://books.google.com/books?id=DvV2Cghvkm8C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

[9] Landsat-4 and Landsat-5 - Earth Online. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://earth.esa.int/eogateway/missions/landsat-4-and-landsat-5#instruments-section

[10] Landsat-4 and 5 - eoPortal. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/landsat-4-5#spacecraft

[11] Krebs, Gunter D. “Progress-M1 1 - 11 (11F615A55, 7K-TGM1)”. Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved October 07, 2023, from https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/progress-m1.htm

[12] Progress (spacecraft) - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progress_(spacecraft)

[13] Krebs, Gunter D. “Progress-M 1M - 29M (11F615A60, 7KTGM)”. Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved October 07, 2023, from https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/progress-m-m.htm

[14] Progress (spacecraft) - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progress_(spacecraft)

[15] STP-1 - eoPortal. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/stp-1#astro-autonomous-space-transfer-and-robotic-orbiter-of-oe

[16] U.S. Air Force to End Orbital Express Mission | Space. (n.d.). Retrieved October 7, 2023, from https://www.space.com/4018-air-force-orbital-express-mission.html#

[17] ESA - Europe’s automated ship docks to the ISS. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/ATV/Europe_s_automated_ship_docks_to_the_ISS

[18] Jules Verne ATV - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Verne_ATV#cite_note-ESA_Docking-17 Huge Cargo Ship Arrives at Space Station Ahead of Shuttle Discovery | Space. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.space.com/10939-cargo-ship-docks-space-station-discovery.html

[19] Johannes Kepler ATV - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Kepler_ATV

[20] Europe’s New Space Rocket Is Incredibly Expensive | The Motley Fool. (n.d.). Retrieved October 7, 2023, from https://www.fool.com/investing/2020/11/10/europe-space-rocket-incredibly-expensive-airbus/

[21] Spaceflight Now | Breaking News | Space station partners assess logistics needs beyond 2015. (n.d.). Retrieved October 7, 2023, from https://spaceflightnow.com/news/n0912/01atvhtv/

[22] Robotic Refueling Mission | NASA’s Exploration & In-space Services. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://nexis.gsfc.nasa.gov/robotic_refueling_mission.html

[23] Krebs, Gunter D. “Progress-MS 01 – 40” Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved October 08, 2023, from https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/progress-ms.htm

[24] Progress (spacecraft) - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progress_(spacecraft)

[25] ISS: RRM3 (Robotic Refueling Mission 3) - eoPortal. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.eoportal.org/other-space-activities/iss-rrm3#mission-status

[26] Krenn, A., Stewart, M., Mitchell, D., Dixon, K., Mierzwa, M., & Breon, S. (n.d.). Flight servicing of Robotic Refueling Mission 3.

[27] ISS: SpaceX CRS-16 (International Space Station: SpaceX Commercial Resupply Service -16 Mission) - eoPortal. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/iss-crs-16#iss-spacex-crs-16-international-space-station-spacex-commercial-resupply-service--16-mission---iss-utilization

- Total mass of satellite was derived from total payload minus other experiment masses

[28] MEV-1 & 2 (Mission Extension Vehicle-1 and -2) - eoPortal. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/mev-1#spacecraft

[29] Anderson, J. (n.d.). Technical Appendix (MEV-2 FCC Application for Authority to Launch). FCC. https://fcc.report/IBFS/SAT-LOA-20191210-00144/2098823.pdf

[30] Another MEV Rescue Mission - BusinessCom Networks. (n.d.). Retrieved October 7, 2023, from https://www.bcsatellite.net/blog/another-mev-rescue-mission/#

- Same mass ratio from MEV-2 was used for MEV-1

[31] MEV-1 & 2 (Mission Extension Vehicle-1 and -2) - eoPortal. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/mev-1#spacecraft

[32] Anderson, J. (n.d.). Technical Appendix (MEV-2 FCC Application for Authority to Launch). FCC. https://fcc.report/IBFS/SAT-LOA-20191210-00144/2098823.pdf

[33] China’s Tianzhou-2 cargo spacecraft docks with space station core module at record-breaking speed, delivers supply for upcoming crewed flight mission - Global Times. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202105/1224902.shtml

[34] ELSA-d CONOPS and Debris Mitigation Overview. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://sa.catapult.org.uk/. https://fcc.report/IBFS/SES-STA-INTR2020-00086/2166969.pdf

[35] Otter Pup Satellite Technical Description. (n.d.). https://apps.fcc.gov/els/GetAtt.html?id=311144&x=

[36] Orbit Fab to launch propellant tanker to fuel satellites in geostationary orbit - SpaceNews. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://spacenews.com/orbit-fab-to-launch-propellant-tanker-to-fuel-satellites-in-geostationary-orbit/

[37] SpaceLogistics Announces Launch Agreement with SpaceX and First Mission Extension Pod Contract with Optus | Northrop Grumman. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://news.northropgrumman.com/news/releases/spacelogistics-announces-launch-agreement-with-spacex-and-first-mission-extension-pod-contract-with-optus

[38] Orbital station-keeping - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orbital_station-keeping

[39] End-of-Life Disposal of Satellites in Geosynchronous Altitude. (2010). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA633333.pdf

- Backing out fuel figure using 6 year mission extension in GEO for 2000kg satellite with ISP = 300 sec needing 45m/sec per year of station keeping

[40] OSAM-1 Decommissioning Orbit Design. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343587900_OSAM-1_Decommissioning_Orbit_Design

[41] This Satellite Tow Truck Could Be the Start of a Multibillion-Dollar Business | Air & Space Magazine| Smithsonian Magazine. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/satellite-rescue-180975337/

[42] Fill ’er up - Aerospace America. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2023, from https://aerospaceamerica.aiaa.org/features/filler-up/

[43] LEO Refueling of Electron/Photon for High-Performance Interplanetary Smallsat Missions. (n.d.). http://www.intersmallsatconference.com/past/2021/E.5%20-%20French/Rocket%20Lab%20-%20ISSC%20Presentation.pdf

[44] US National Science and Technology Council. (2022). National In-Space Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing Implementation Plan. Executive Office of the President of the United States. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/NATIONAL-ISAM-IMPLEMENTATION-PLAN.pdf

[45] US National Science and Technology Council. (2022). National In-Space Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing Implementation Plan. Executive Office of the President of the United States. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/NATIONAL-ISAM-IMPLEMENTATION-PLAN.pdf

[46] ISO. (2022). ISO 24330:2022(en), Space systems — Rendezvous and Proximity Operations (RPO) and On Orbit Servicing (OOS) — Programmatic principles and practices. ISO Standards. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:24330:ed-1:v1:en

[47] RAFTITM — Orbit Fab | Spacecraft Refueling. (2023). Orbit Fab Website. https://www.orbitfab.com/rafti/

[48] Li, W. J., Cheng, D. Y., Liu, X. G., Wang, Y. B., Shi, W. H., Tang, Z. X., Gao, F., Zeng, F. M., Chai, H. Y., Luo, W. B., Cong, Q., & Gao, Z. L. (2019). On-Orbit Service (OOS) of Spacecraft: A Review of Engineering Developments. In Progress in Aerospace Sciences (Vol. 108, pp. 32–120). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paerosci.2019.01.004

[49] Hudson, J. S., & Kolosa, D. (2020). Versatile On-Orbit Servicing Mission Design in Geosynchronous Earth Orbit. Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, 57(4), 844–850. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.A34701

[50] Jones, H. W. (2015). Estimating the Life Cycle Cost of Space Systems. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20160001190/downloads/20160001190.pdf

[51] Saing, M. (2020). NASA and Smallsat Cost Estimation Overview and Model Tools. https://www.nasa.gov/wpcontent/uploads/2020/05/saing_nasa_and_smallsat_cost_estimation_overview_and_model_tools_s3vi_webinar_series_10_jun_2020.pdf

[52] Beyond the Metal: Investigating Soft Robots at NASA Langley - NASA. (n.d.). Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://www.nasa.gov/centers-and-facilities/langley/beyond-the-metal-investigating-soft-robots-at-nasa-langley/

[53] Palmieri, P., Melchiorre, M., & Mauro, S. (2022). Design of a Lightweight and Deployable Soft Robotic Arm. Robotics 2022, Vol. 11, Page 88, 11(5), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ROBOTICS11050088

[54] This Gecko-Inspired Robotic Gripper Could Help Clean Up Space Junk. (n.d.). Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenniferhicks/2021/05/20/this-gecko-inspired-robotic-gripper-could-help-clean-up-space-junk/?sh=5b804d812426

[55] Sticking Around: Astrobee Tests Gecko-Inspired Adhesives in Space - NASA. (n.d.). Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://www.nasa.gov/image-article/sticking-around-astrobee-tests-gecko-inspired-adhesives-space/

[56] Spenko, M. (2023). Making Contact: A Review of Robotic Attachment Mechanisms for Extraterrestrial Applications. Advanced Intelligent Systems, 5(3), 2100063. https://doi.org/10.1002/AISY.202100063