High-Speed Rail Safety

Roadmap Overview

High-Speed Rail is a type of passenger rail transportation system that operates at high-speed with high voltage electricity. With respect for the multiple definitions for high-speed rail, the International Union of Railways defines high-speed rail as systems of rolling stock and infrastructure which regularly operate at or above 250 km/h on new tracks, or 200 km/h on existing tracks. Figure 8, above, shows the basic components of high-speed rail system. Rolling stock that obtain electricity from cable (as shown, or ground-based rail) as a power is operated by a driver who follows signals and communicates with one or more control centers. The dedicated or specifically upgraded tracks guide the train.

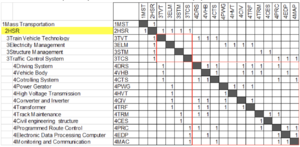

DSM Allocation

The DSM shows that the 2HSR is part of the mass transportation system in large context. It requires 3TVT Train Vehicle Technology, 3ELM Electricity Management, 3STM Structure Management, and 3TCS Traffic Control System. In addition, these level 3 technologies require level 4 technologies that are consist of 4 DRS Driving System of the vehicle such as motor, 4VHB Body of vehicles, 4CTS control system of the vehicle, 4PWG power generator or power plant of electricity, 4HVT technology for transmitting high voltage electricity, 4CIV converter and inverter inside the vehicle, 4TRF transforming electricity to appropriate voltage, 4TRM maintenance of tracks, 4CES maintenance of civil engineering structures such as bridges and tunnels, 4PRC route control system, 4EDP data processing unit, 4MAC technology for monitoring and communicating data.

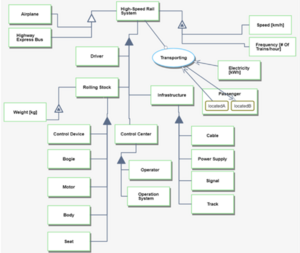

Roadmap Model using OPM

The OPM describes the decomposition and primary function of HSR system. The level 1 decomposition of the system is Driver, Rolling Stock, Control Center and Infrastructure. Rolling Stock consists of physical components such as bogie and body. The main components of control center are Operator and Operation system that support drivers by providing information from several data sources and calculating the signal pattern. Infrastructure, such as tracks and signals, is the foundation of the system that physically and electrically support the operation.

Figures of Merit

| Figure of Merit | Units | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum speed | km/hour | Maximum operational speed of trains |

| Frequency | # of trains/hour | Number of operated trains per hour |

| Weight | kg | Weight of train |

| Brake force | N | Force to stop the train |

| Brake stopping distance | m | Distance that it takes to come to a complete stop |

| Capacity | people/train | Number of passengers carried by train |

| Strength of Body | N/mm^2 | Strength against crash |

| CO2 emission | t/train/km | Amount of CO2 emitted by electricity generation used for operating one train |

| Construction cost | $/km | Initial cost for constructing total railway system per 1 km |

| Operation cost | $/train | Operational cost for a round-trip of a train |

Alignment with Company Strategic Drivers

Strategic Driver: To develop a safe, comfortable, and punctual high-speed train system that can stop as quickly as possible to minimize the possibility of collision and derailment.

Alignment and Targets: The HSR Technology Roadmap will target a dedicated track-guided system with powerful brake that can decelerate at 1.5m/s^2 and an obstacle sensor system that can detect and respond to any dangerous obstacle immediately. This driver is currently aligned with the HSR technology roadmap.

The continuous goal for the railway business is to develop a safe and convenient train system that is attractive to potential passengers. In the context of safety, the braking time should be as short as possible without injuring passengers due to a too intense jerk (jerk is the derivative of acceleration). The simplest way to reduce the braking time is to reduce speed. This approach is accepted by passengers when the train is traveling under bad conditions, such as heavy rain or mechanical troubles. Also, the total weight (vehicle weight + passengers’ weight) of the train would affect the braking time. In this context, reducing capacity would contribute to reduced braking time. However, operating at reduced profitability and efficiency, by reducing operational speed and capacity, would negatively affect the attractiveness of the system to passengers.

Positioning of Company vs. Competition

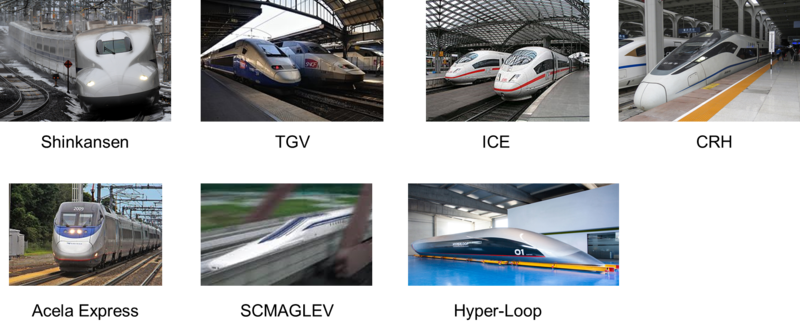

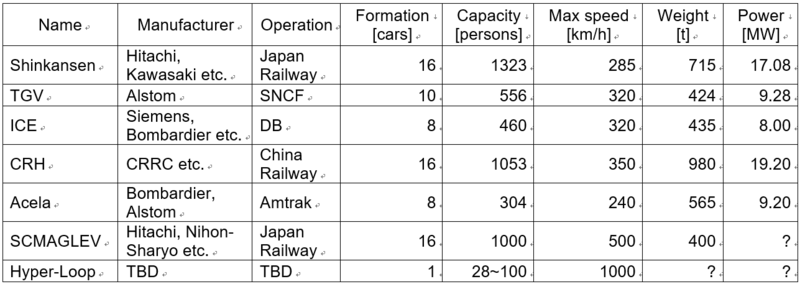

The figure below shows a summary of several types of high-speed rail systems, derived from public data. The Shinkansen in Japan has the largest capacity in the world and these trains are formally operated at a fixed number of cars. In Europe and China, the number of cars can change flexibly based on regions’ needs and the types of models. This flexibility better supports variabilities in demand but affects the operating cost and makes driving the vehicle more difficult. Typically, operational speed is capped by sharpness of curves and the strength of track components and infrastructure. China Railway has the highest operational speed supported by newer track and infrastructure and fewer sharp curves. However, unconventional systems such as maglev and hyper-loop, using totally different propulsion and guiding systems, enables trains to be operated at much higher speeds. The SCMaglev is now under construction in Japan and operating in test mode, while Hyper-loop systems are still in a concept phase and need further development to their core system. The table below also shows that the Acela Express is less efficient compared to other high-speed rail systems, with lower speed, less capacity, and heavier vehicles.

Technical Model

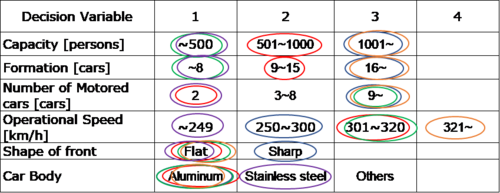

Table below shows the morphological matrix of the main technological decision variables on high-speed rail that would affect breaking system and safety. Five conventional railway systems (Blue:Shinkansen, Red:TGV, Green:ICE, Orange:CRH, Purple:Acela) are plotted on the matrix. Note that the architecture of the motor is different between TGV/Acela and others. These two trains are push-pull, with locomotives at both ends of the train, which has the advantage of flexibility in the number of cars between the locomotives and interoperability with local tracks. However, this configuration has a disadvantage with efficient braking because less motors acting on less axles are available to electrically deaccelerate the vehicle. The shape of the front affects air drag and noise when running at high speed. The Shinkansen is shaped carefully so that it can minimize noise that would adversely impact urban areas and going through tunnels. JR East is trying to develop air flaps that can increase air drag as part of emergency braking systems. To minimize weight, most rail systems use aluminum because it is light and easy to handle. Some companies are exploring the use of alloyed magnesium or carbon-fiber for the car body, but these technologies are not yet in production.

(Blue:Shinkansen, Red:TGV, Green:ICE, Orange:CRH, Purple:Acela)

(Blue:Shinkansen, Red:TGV, Green:ICE, Orange:CRH, Purple:Acela)

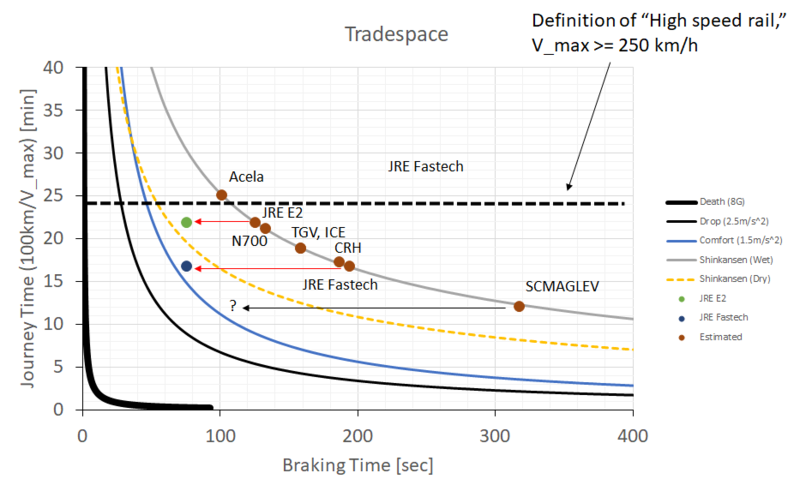

Figure below shows the tradespace between journey time and braking time. Note that the definition of “High Speed Rail” is that the maximum sustained speed of a train in service is over 250 km/hour, which is shown as the black dotted line. In addition to the frontiers of Shinkansen JRE2 in both wet (solid line) and dry (dashed line) conditions, the frontier in 8G deceleration (Death), one where passengers cannot keep their seats (Drop), and one in comfort situation (Comfort), that is, the passengers are able to hold on or remain seated as the train decelerates. Also, the estimated values of braking time and journey time of several high-speed trains, whose characteristics are shown in Table 4-3, are plotted under the condition that all the parameters except for mass and the maximum velocity are the same. For JRE E2 and JRE Fastech, the values written in [5] are also plotted as red circle and blue circle, respectively, to compare the actual values and the estimated values.

Calculations reveal that, even when the weather is dry, the deceleration due to the adhesion friction is low enough that passengers can keep their seat with comfort. As the actual values of JRE E2 and JRE Fastech are closer to the “Comfort” curve, recent research has enabled more efficient braking to reduce the braking time.

The SCMAGLEV is propelled by electromagnetic force, not by friction between the vehicle and the rail. This difference is indicated by unique behavior in the tradespace. The SCMAGLEV has potential to decelerate hard enough to drop passengers from their seats, which means SCMAGLEV theoretically can operate beyond the “Drop” curve. However, from the viewpoint of passengers’ safety, it cannot go beyond “Drop” curve unless restraints or other instruments are installed to keep the passengers in their seats during emergency braking.

Keys Publications and Patents

The following papers and patents were reviewed:

Anti-derailment

- US Patent 2,800,861, Anti-derailing device, Joseph Michalski, Vestaberg, PA, 30 July 1957

- US Patent 3,084,637, Safety Derail Preventer, Frank W. Kohout, Pacific Palisades, CA, 9 April 1963

- Nicholas Wilson, Robert Fries, Matthew Witte, Andreas Haigermoser, Mikael Wrang, Jerry Evans, and Anna Orlova (2011) Assessment of safety against derailment using simulations and vehicle acceptance tests: a worldwide comparison of state-of-the-art assessment methods, Vehicle System Dynamics, 49:7, 1113-1157

- Jing Zeng & Qing Hua Guan (2008) Study on flange climb derailment criteria of a railway wheelset, Vehicle System Dynamics, 46:3, 239-251

Object detection

- US Patent 5,787,369, Object Detection System and Method for Railways, Theodore F. Knaak, Orlando, FL, 28 July 1998

- US Patent 5,978,718, Rail Vision System, Westinghouse Air Brake Co., Wilmerding, PA, 2 November 1999

- US Patent Application 10/251,422, Railway Obstacle Detection System and Method, James R. Jamieson, Savage, MN and Mark D. Ray, Burnsvile, MN, 20 September 2002

- Yong-Ren Pu, Li-Wei Chen, and Su-Hsing Lee, Study of Moving Obstacle Detection at Railway Crossing by Machine Vision, Information Technology Journal 13 (16) 2611-2618, (2014)

Track condition

- P.A. Costa, A. Colaço, R. Calçada, A.S. Cardoso, Critical speed of railway tracks. detailed and simplified approaches, (2014)

- Ali Al-Shaer, Denis Duhamel, Karam Sab, Gilles Forêt, Laurent Schmitt. Experimental settlement and dynamic behavior of a portion of ballasted railway track under high speed trains. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Elsevier, 2008, 316, pp.211-233. 10.1016/j.jsv.2008.02.055

- J. P. Powell, R. Palacin, Passenger Stability Within Moving Railway Vehicles: Limits on Maximum Longitudinal Acceleration, NewRail - Centre for Railway Research, Newcastle University, 14 August 2015

Braking

- Lionginas Liudvinavičius & Leonas Povilas Lingaitis (2007) Electrodynamic braking in high‐speed rail transport, Transport, 22:3, 178-186

- Jie Liu, Yan-Fu Li, Enrico Zio, A SVM framework for fault detection of the braking system in a high speed train, Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 87 (2017) 401–409

- Hiroshi Arai, Satoru Kanno, Naohito Yanase (ND), Special Edition Paper – Brake System for Shinkansen Speed Increase, JR EAST Technical Review-No.12 PP12-15, https://www.jreast.co.jp › development › tech › pdf_12

- Piers Connor (2014), High Speed Railway Capacity – Understanding the factors affecting capacity limits for a high speed railway, 1964-2014 High Speed Rail: Celebrating Ambition. University of Birmingham, 8-10 December 2014, http://www.railway-technical.com/books-papers--articles/high-speed-railway-capacity.pdf

- David Barney, David Haley and George Nikandros, Calculating Train Braking Distance, Signal and Operational Systems, Queensland Rail (Copyright © 2001, Australian Computer Society, Inc. This paper appeared at the 6th Australian Workshop on Safety Critical Systems and Software (SCS’01), Brisbane. Conferences in Research and Practice in Information Technology, Vol. 3. P. Lindsay)

The Japanese high-speed rail tracks are isolated through elevation or fencing such that many potential obstructions are avoided. However, the tracks are still subject to earthquakes and the potential for large objects such as trees to be blown onto the tracks. Other country’s tracks are not as well protected, and as high-speed rail is adopted in countries with much longer distances to travel the cost to isolate the tracks may prove to be prohibitive. As such, other safety systems will be needed to keep passengers, communities, and rail rolling stock safe.

Anti-derailment systems come in several forms. Systems for low-speed use included additional hardware to stop the wheels from jumping the track and to keep the wheels close to the track once derailed. Later systems included improved wheel flange design to avoid the wheel riding up on the flange in curves. Improvements to truck (bogie) designs and couplers reduced tolerances in severe braking as well as reducing sway at high speed. Modern high speed rail designs typically include simulation tools to detect potential design issues that might cause instability at high speed.

The original track detection systems were signals so that one train operator would know how far ahead the next train was. Modern safety systems for track obstructions include camera and other optical systems to detect objects on the track ahead of the train. Some of these systems are train mounted, using lasers and detectors for range finding and including reflective components to allow these systems to detect objects not in straight line of sight of the train. Other systems include track-side cameras and pattern detection is increasingly common to flag potential obstructions. State of the art systems include automatic detection and activation of brakes. The SCMAGLEV has no on-board operator; presumably while humans control the train remotely many of the emergency detection systems are partially or fully automated.

The design of the track has itself been adapted to support high speed rail. Superior rail, track, and bed design and implementation reflect the increased longitudinal and latitudinal forces on the rails and these forces’ transfer through the ties into the ballast and bed. The ability of the rails to withstand the extended braking force of a high-speed train coming to an emergency stop has been researched and modeled to ensure that the tracks do not distort under extreme loads.

Brake system design is the most critical issue for emergency braking right now. Converting the kinetic energy of a heavy and fast moving train to heat and then dissipating that heat is the current limiting factor for stopping distance. Disk brakes, as found under the Acela and other trains, is now considered state of the art. Load balancing systems are also deployed to avoid derailment while maximizing brake application when the back of the train is heavier than the front. Overall braking performance may be improved with driveline design changes, for example the Shinkansen has each axle powered, offering the opportunity to use the motors to further apply substantial decelerating forces on the wheels. By comparison, the Acela has a leading and trailing locomotive, with the passenger rolling stock left with wheel brakes only.

Modern high speed rail has matured extended object detection, track quality, and stability. Currently braking is limited by brake system capability. Based on the research completed for this assignment, it is our opinion that once braking effectiveness is achieved, the limiting factor will be passenger safety – slowing the train too rapidly with unrestrained passengers will cause more injuries that it might save. However, with the acceptance of passenger restraints this cycle of object detection, track quality, stability, and braking could begin again.