Plant Genetic Improvement

Technology Roadmap Sections and Deliverables

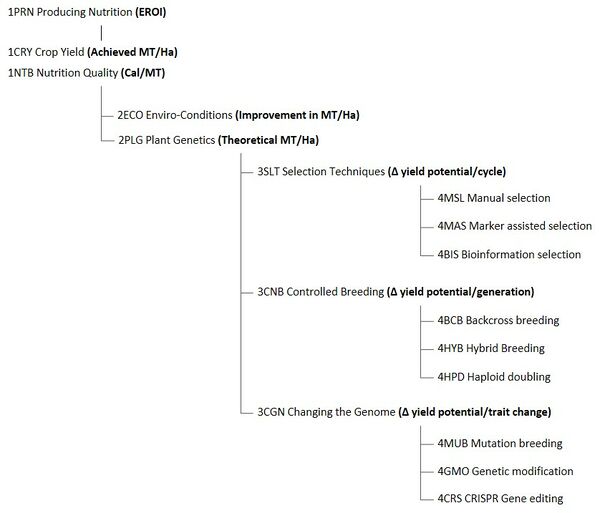

The goal of Plant Genetics Improvement is usually to achieve better outcomes in crop production in the form of more Useful Crop Yield. These improved outcomes can be either increased yield, better quality or improved tolerance. The science of Plant Genetic Improvement has traditionally been the domain of the plant breeder. The technology used for Plant Genetic Improvement consists of both tools and methods as shown below:

Our roadmap is focused on the technologies which contribute to improving 2PLG Plant Genetics and the key Figure of Merit (FOM) is Theoretical MT/Ha.

Roadmap Overview

Plant Breeders contribute to increasing Useful Crop Yield (1CRY) and they do this through the science of improving Plant Genetics (2PLG).

Plant Breeders control a gene pool in distinct phases - firstly variation - allowing or encouraging wide variability in the genotype, secondly selection of plants with desirable phenotypes (characteristics). Finally, plant breeders then aim to eliminate variability from the gene line of the selected plan, in order to produce a consistent gene line for crop production

In summary, plant breeding is based on these key phases: Create variation → Selection → Eliminate variation and the plant breeder achieves this through the major technologies (both tools and methods, with discovery year in brackets) as follows:

- Selection Techniques (3SLT)

- Manual selection (4MLS) a traditional approach which has been carried out for thousands of years.

- Marker assisted selection (4MAS) – a genetic technique where a genetic marker is placed in the genome next to a desirable genetic characteristic which allows desirable plants to be selected before the trait is exhibited in the phenotype. (1986)

- Bioinformatic selection (4DSB) – a bioformatic technique to identify favorable characteristics from the sequenced genetic information of a plant. (2008)

- Controlled Breeding (3CNB)

- Backcross introgression breeding (4BIB) – a breeding technique to move a desirable characteristic from one plant to another line of plants. (1922)

- Hybridization (4HYB) – A natural phenomena where the offspring of purebred parent lines are more healthier than their parents, but themselves sterile. (1926)

- Haploid doubling (4HPD) – a laboratory technique which can create stable parent lines through a laboratory process, rather than seven field seasons of inbreeding. (1959)

- Changing the Genome (3CGN)

- Mutation breeding (4MUB) – a breeding technique which uses primitive methods to force variation in a plant population – for example using exposure to radiation. (1930s)

- Genetic modification (4GMO) – genetic engineering techniques to introduce non-host species genetics into a plant from say a bacteria or different plant species. (1982)

- CRISPR Gene editing (4CRS) – latest genetic technique to be able to cut and paste gene sequences between plants in the laboratory. (2012)

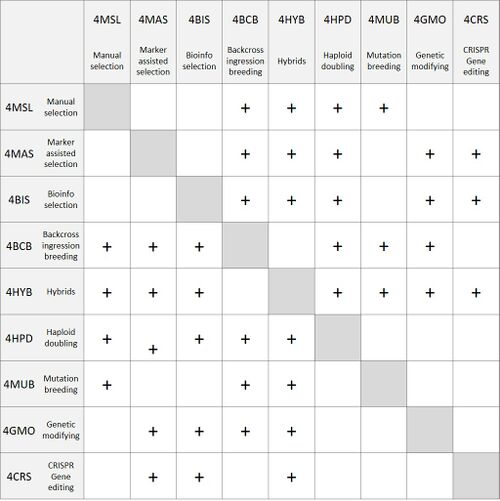

Design Structure Matrix (DSM) Allocation

The DSM is used to show the interaction between tools and methods which make up Plant Genetic Improvement. The + sign indicates that the techniques are compatible and can be used together.

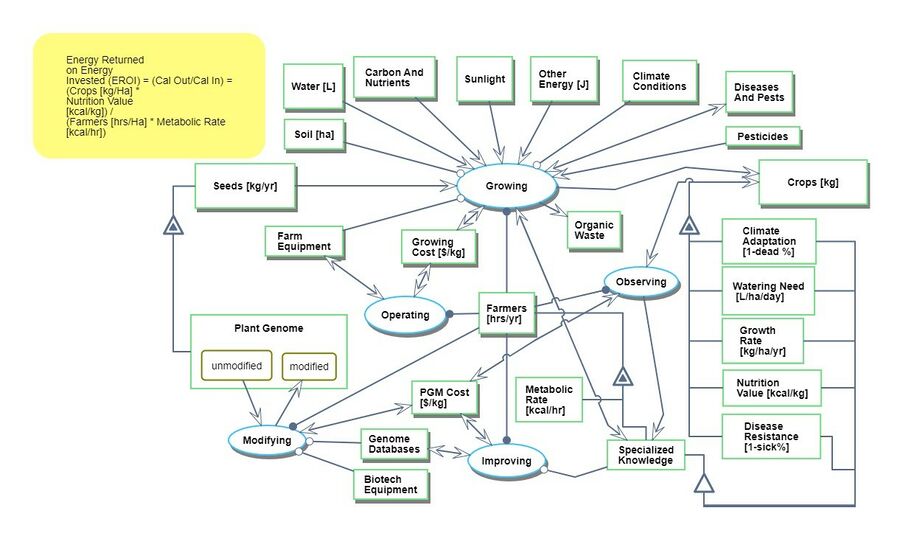

Roadmap Model using OPM

We provide an Object-Process-Diagram (OPD) of the Plant Genetic Improvement roadmap in the figure below. This diagram captures the landscape in which Plant Genetic Improvement belongs and the interfacing systems with which it fits.

An Object-Process-Language (OPL) description of the roadmap scope is auto-generated and shown on the right. It reflects the same content as the previous figure but in a formal natural language.

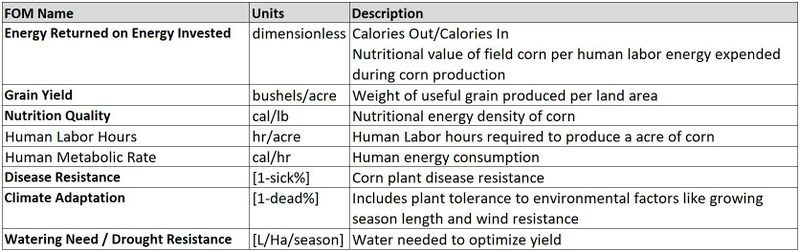

Figures of Merit

The table below shows a list of FOMs by which plant genetic improvements can be assessed.

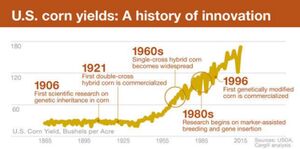

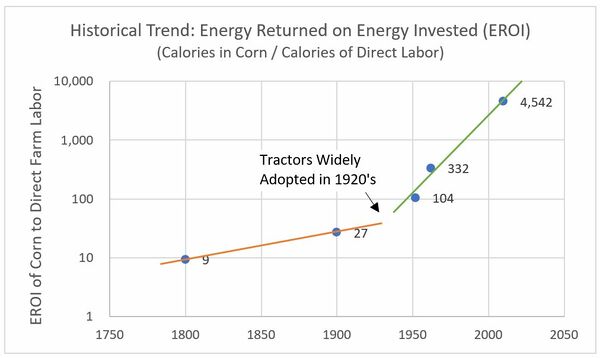

To understand the historical progression of EROI and predict future possible EROI's, we plotted EROI based on a literature search of the changing yield [Bu/Ac] and productivity [hrs/Ac] over time. Our literature search did not reveal significant changes in nutrition or density over time. The trend line changes in the 1920's, primarily contributed to the introduction of the mechanized tractor which significantly reduced the person-hours per acre. Other agricultural enhancements such as improved plant genetic improvements (hybrids), fertilization techniques, and pesticide use also contributes to the increase in yields over time.

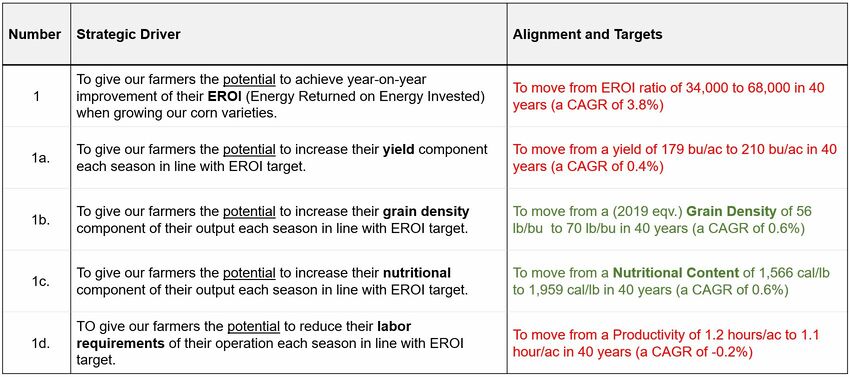

Alignment with Company Strategic Drivers

Our company has a vision to provide farmers with seeds which enable them to continually improve their Energy Returned on Energy Invested, and the roadmap relates to technologies which enable this vision.

Of course, there are other growing factors (both inside or outside of the farmers control) that impact Energy Returned on Energy Invested - these other factors are shown on the Roadmap Tree as '2ECO Enviro Conditions'. Therefore, our company can only provide to the farmer the genetic potential to achieve improvement.

In our Plant Genetic Improvement business, we manage a small portfolio of varieties, and an R&D pipeline of new varieties. This is similar to how the pharmaceutical industry manages a pipeline of drugs. Each year our R&D pipeline produces several new varieties with incremental improvements on previous varieties. For this reason, our targets for each driver are shown in terms of a small, statistically-proven percentage improvement over previous varieties.

Positioning of Company vs. Competition

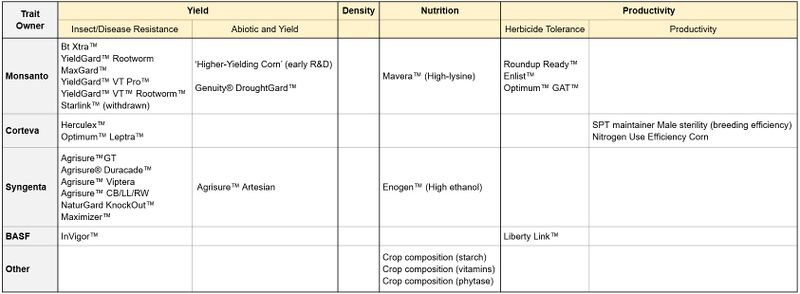

The table below summarizes all the GM traits registered for use in corn in the US. The left-most column shows the owner-company which owns the trait and which is also likely the discoverer. This owner-company can and will be licensing these traits to the other seed companies shown here, and many other small seed companies across the US.

Data is not available that allocates yield, density, nutrition, or productivity improvements per corn variety. Therefore, we developed the table below to describe the competitive environment by determining the "hot spots" of current breeding outcome. The key insight is that current competition is mainly focused on improving yield. Today's commercial corn infrastructure drives this focus on yield, because growers are paid by weight. The areas of Density, Nutrition, and Productivity are potentially under-served markets, that provide value by improving EROI.

The trait competitive landscape table shows the environment which we would face as a small biotechnology start-up which is trying to find a position in the corn trait market. Of course, trait development programs can take 10-20 years to bring to market (10 years with new technology that reduces cycle time). We must compare the table above, against our company goal which is ‘giving farmers the potential to improve their Energy Returned on Energy Invested (EROI)’ and the drivers of this which are: yield, nutritional content, density, and productivity.

- Yield – there are many traits which are designed to ‘protect’ yield from insect and disease damage, and abiotic stress. There is only one trait (in early development) which is actually targeting the genetic source of increased yield. Regardless, this is a crowded space and likely not an opportunity.

- Density – No traits on market or in development to improve the volumetric density of corn. This could be a potential target for our company. Our 16.887 team has conducted interviews with corn breeders in the last few days who suggest that this could be a commercially viable trait and an achievable R&D objective.

- Nutrition – There are several nutritional traits in development or on market, but only one focused on calorific energy (starch) – this trait is in early R&D at a university in Spain. In corn, the calorific energy is stored in the form of carbohydrates as both starch and sugars. There is an opportunity for our company to pursue increasing the calorific energy of corn as an R&D objective.

- Productivity – There are many productivity traits including the most successful – RoundupReady herbicide tolerance. Productivity traits are a more challenging target for a small independent biotech company – very often productivity traits involve cross-discipline technology partnerships (for example RoundupReady is a cross-discipline technology involving genetics and agrochemicals).

In summary, the competitive chart suggests that our initial R&D efforts should focus on understanding the plant physiological pathways that are responsible for Grain Density, as well as increasing the Nutrition - Calorific Value of Grain as these are unmet by the incumbent seed trait companies.

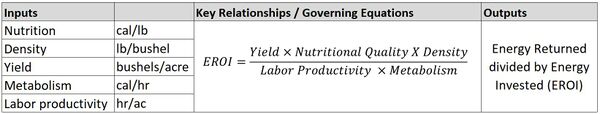

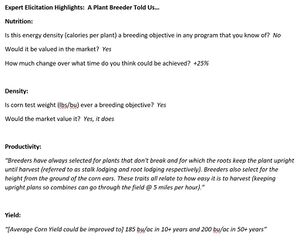

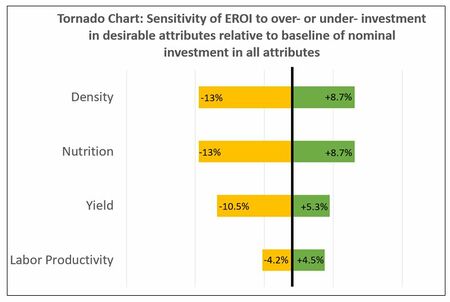

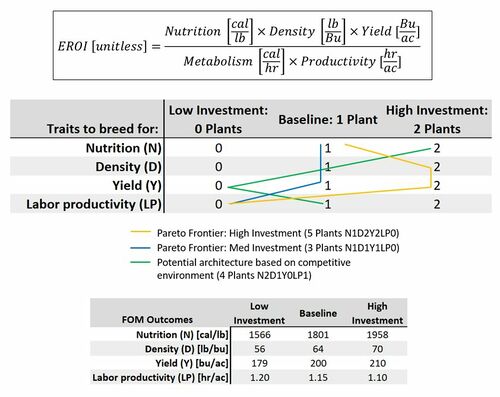

Technical Model

As metabolic rate can be considered constant for a human farm worker, the other four parameters, Nutrition (N), Density (D), Yield (Y) and Labor Productivity (LP) are targeted for improvement via the technology of Plant Genetic Modification. To obtain estimates of the likely future evolution of each of these four parameters, we performed a literature review and elicited expert opinions through a mini-survey. From the tornado chart, we note that density and nutrition are the two parameters that EROI is most sensitive to, followed by yield and labor productivity.

The tradeoff is the time and costs it takes to develop, obtain approval for and roll out a new trait. Based on our literature review, we found that investment in a new genetically modified plant is a long process which takes ~20 years to complete with a total cost of $136m[1]. For our fictional company, we set a budget of $700m in R&D spending (I.e. up to 5 plants at the cost of $136m per plant), and generated a number of feasible architectures with investment in 0-5 plants where each plant targets Nutrition, Density, Yield or Labor Productivity.

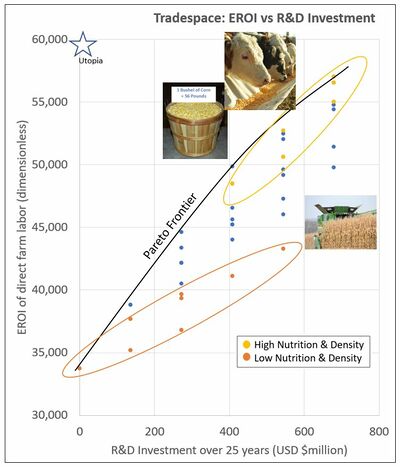

The morphological matrix below summarizes project architectural decisions of how many plants with which traits to commit to developing over the next 25 years. Choices are low investment (0 plants), baseline (1 plant), or high investment (2 plants). The projected achieved FOM per investment is shown in the FOM outcomes chart.

The resulting architectures are plotted in a tradespace of cost vs. EROI, always with respect to the energy invested by direct farm labor. The key takeaway from the tradespace is that architectures that don't focus on improving nutrition or density are fully dominated. Architectures that commit resources to developing plants with better nutritional content and higher density are found along the Pareto frontier.

Financial Model

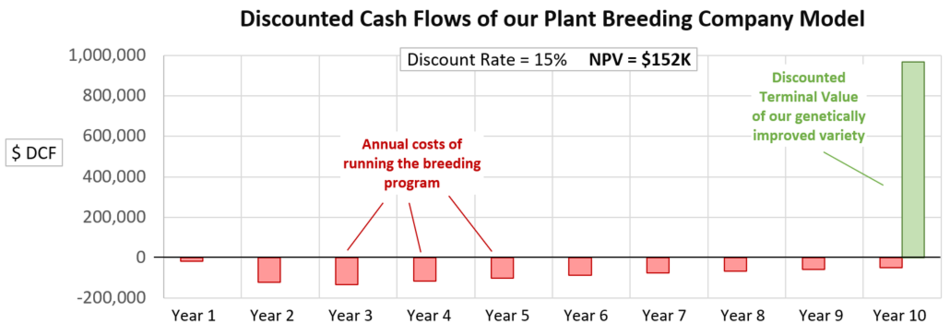

Plant breeding is a financially challenging endeavor because of the long timeframes involved, typically 10 years to develop a new variety, and therefore Net Present Value financial analysis which takes into account the time value of money is especially applicable. This section will consider how a small plant breeding company would use NPV to decide how to make technology investments.

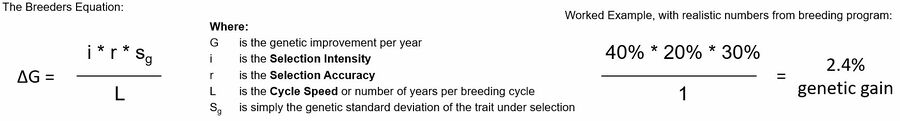

First, we have to understand the activity which a plant breeding company will be undertaking. Plant breeding improves a population of plants in terms of a key characteristic such as yield. The plant breeder starts with the first generation of plants and selects the best ones (those exhibiting the high yielding characteristics) to take forward to the following generations. By selecting from each subsequent generation, the overall yield characteristic of the population can be improved. The Rate of Genetic Improvement in plant breeding is measured by a well-known governing equation known as the ‘Breeders Equation’:

Technological innovations in plant breeding contribute to improving these underlying drivers of plant breeding; some examples of breeding technology are (with expected gain based on our research):

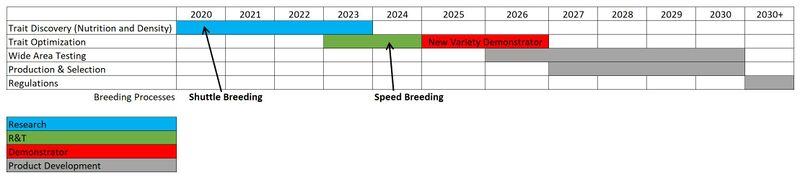

- Driver: Cycle Speed – how fast a selection cycle can be made. The baseline is one selection per year.

- Shuttle breeding (1960s) where genetic lines are shipped around the world to take advantage of three climates in a year (x3 gain)

- Speed Breeding (2000s) uses protocols such as artificial light and temperature to rapidly express phenotype characteristics (x1.5 gains)

- Driver: Selection Intensity – High Intensity would be taking forward the best 1% of plants, Low Intensity would be taking forward the best 50% of plants each cycle. Improvement is possible by increasing the population sizes for equal resource spent, and examples include:

- Phenocart (2016) is a low-cost, hand-pushed phenotyping device with multispectral sensors and used to quickly phenotype breeding plots (+7% gain over manual methods)

- Rapid phenotyping (starting early 2000s) using remote sensing and computer vision to increase the population's size (+25-75% faster data collection with drones)

- Driver: Selection Accuracy – are the correct gene lines being carried forward to the next cycle.

- Marker-assisted selection (4MAS) (1980s) - using introduced or natural patterns in DNA to identify which candidates will exhibit the desired phenotype. (up to +50% gain in accuracy)

- Genomic data selection methods(4DSB) (2000s) to improve accuracy is increasing. A recent paper details how by using high-throughput measurements of plant temperature and light reflectance combined with genomic information, predictions of yield achieved accuracy over traditional selection (+7% over standard genomic selection models)

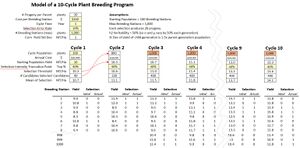

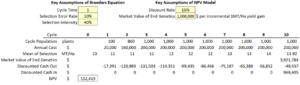

The small plant breeding company will have to decide how to invest in the above technology and can use Net Present Value methodology and the Breeders Equation to decide where to spend its technology budget. Each dollar spent on technology will have an impact on the Breeders equation and ultimately lead to higher returns when the seed variety is commercialized. In order to understand the returns from investing in each driver over a ten-year breeding program, a small quantitative model of a seed breeding pipeline has been built. Note that the model uses Yield as a breeding objective (although in the future Density and Nutrition can be objectives as per our plan above). This makes the following assumptions:

Assumptions of our Plant Breeding Financial Model

| Starting Population = 100 Breeding Stations | Max Breeding Stations = 1,000 |

| Each selection produces 20 progeny | h2 heritability = 50% (so σ and μ vary by 50% each generation) |

| St Dev of yield of child generation = 1.5x parent generation population | Breeding costs $20,000 per breeding station per year (all-in) |

| Program runs for 10 cycles | Starting cycle time is one year |

| Plant yields standard deviation is constant at 1MT/Ha | Breeding Objective = Yield in MT/Ha |

| Starting Yield = 10Mt/Ha | Selection error equally weighted between recall and precision |

The financial model below shows the Discounted Cashflow Profile for our plant breeding program - this is a very typical profile, with high cash outflow for 10 years and then a valuable genetic line at the end. Regardless of this financing challenge, our program shows a total cash requirement (discounted) of about $800K over ten years and then a positive NPV of $190K based on our assumptions, which are realistic from industry sources. The model also allows optimizing the three drivers of the Breeders Equation (Selection Intensity, Selection Accuracy and Cycles per Year) and understanding how they affect NPV.

List of R&T Projects and Prototypes

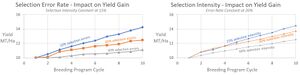

In order to select and prioritize R&D technologies that our small plant breeding company should invest in, we used the operational model [the same as in Financial above] to estimate the impact of making changes to parameters of the Breeders Equation. The main assumption was that the specific plant breeding improvements mentioned above in the Financial Section could be realized over a 10-year timeframe. We also assumed that the improvements were additive and realizable in full. Therefore, in this 10-year period, the Breeders Equation levers can be improved as follows:

- Cycle Time can be made faster because Shuttle Breeding can gain x3 and Speed Breeding can gain x1.5 - a x4.5 gain in total.

- Selection Intensity can be improved because a Phenocart can gain 7% and Rapid Phenotyping with drones can gain 50%, a total of 57%.

- Accuracy can be improved by 57% because Marker Assisted Selection can gain +50% and Genomic Data Selection Methods can gain another +7%.

Insight from our Operational Model indicates investment in reducing breeding Cycle Time has the most dramatic impact on genetic improvement.

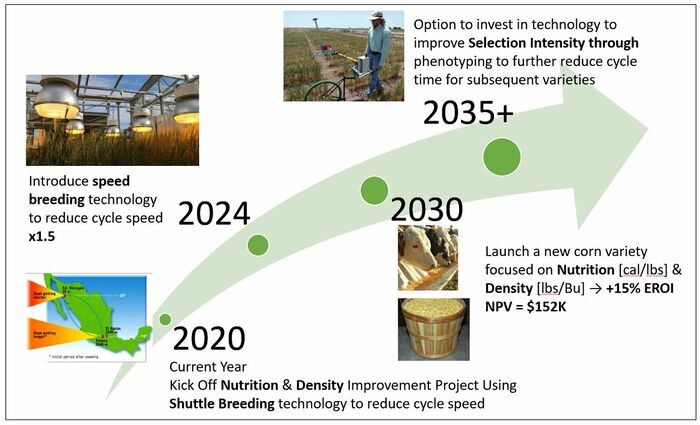

The following Gantt chart highlights key milestones in the development of a new corn variety.

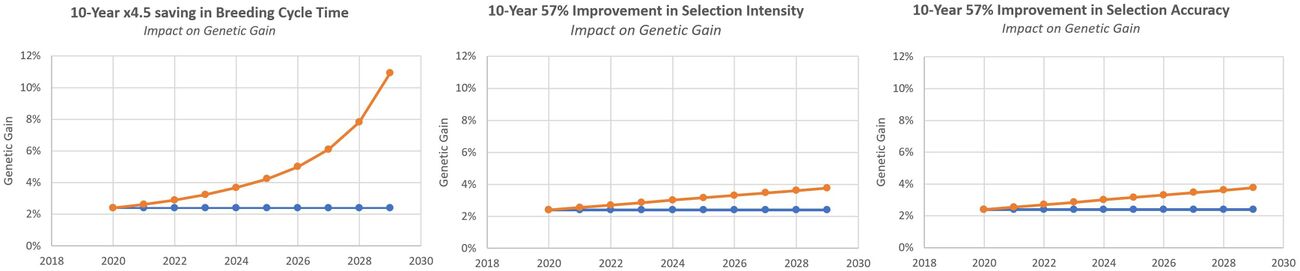

Key Publications, Presentations and Patents

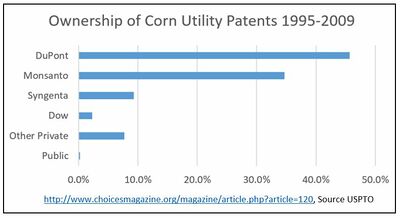

As shown in the charts below, the number of agricultural biotechnology patents has increased significantly in the last 20 years, and a few large corporations hold the majority of the corn utility patents in the US. As of 2009, Dupont, Monsanto, and Syngenta, and Dow held over 90% of all the corn utility patents. In 2015, Dow and Dupont merged into Dow-Dupont, further reducing the distribution of patent ownership.

Compared to other technologies, the patents that are granted for genetically modified (GM) plants give inventors a wide scope of authority. The patents granted cover not only the plant itself but also strongly influence any subsequent technologies and research-based off the original invention. This is mainly driven by US patent policy that grants both plant patents and utility patents. For example:

- the plant patent protects against others duplicating the plant breed, selling the plant, or importing the plant from outside the US

- the utility patent protects the plant itself and its descendants, while also covering the method of production and the uses of the plant

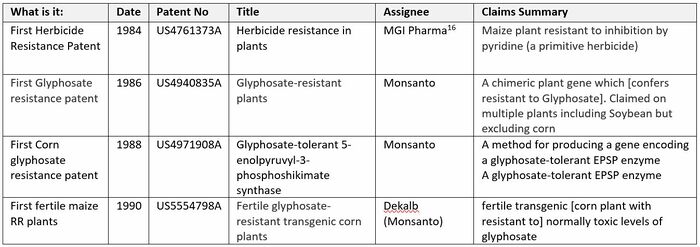

The patents around corn genetic modification are complex as protection is spread across multiple patents – sometimes the gene is patented, or a method to make it or insert it or the location on the chromosome. However, the table below shows what we consider to be some of the key patents from the early period of glyphosate-resistance genetic modification in the 1980s.

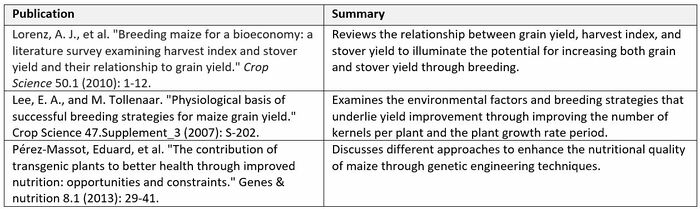

The table below shows what we consider to be some of the key publications related to breeding corn for improved yields, improved density, improved nutritional content, or improved productivity.

Technology Strategy Statement

The goal is to improve the ratio of Energy Returned on Energy Invested (EROI) of a population of corn plants by improving plant performance of two attributes, firstly Density of Grain per Unit of Volume in-lbs per bushel (a 15% gain in Grain Density can lead to a 14.3% gain in EROI) and secondly, calories per unit of mass in calories per lb (15% gain in Nutritional Value can lead to a 15% gain in EROI). These are attributes that have not been targeted by plant breeders and so may allow us a niche in the market.

We are going to achieve this over a 10 year breeding program (go to market with new varieties in 2030) and focus investments on technology which will allow us to reduce Cycle Time [our financial modeling shows that] this is the most impactful lever which a small company has. The initial technologies which we will use include Shuttle Breeding and Speed Breeding.

By making targeted technology investments, we can help to feed a growing population. It's generally accepted that agricultural production needs to double in the next 50 years to keep up with the increased demand from a growing population and expanding middle class. Continual improvements to Plant Genetics is critical for mankind, and it's the foundational global trend that will support the growth of our company. Our approach explored Energy Returned over Energy Invested (EROI) as an alternate measure for understanding the rate of Plant Genetic Improvement. We also explored a range of technological innovations that contribute to Plant Genetic Improvement through traditional Plant Breeding and scientific genetic trait development.

Beyond our small corn breeding company, here is a potential 30+ year Technology Outlook (Estimated Year) for plant genetic improvements within the industry.

- HPPD Herbicide Tolerance (2020): A valuable alternate chemistry in the fight against herbicide resistance

- CRISPR gene editing (2022): Precise editing of native traits into crops

- Meat Substitutes (2025): Heme which is a molecular structure which makes up Hemoglobin in blood and gives meaty its red color and meaty taste. Soybeans have just been engineered to produce Heem which forms the basis of new alternative meat products. There are coming opportunities to engineer plants to produce other meat components meaning meat equivalents can be produced directly from plants and avoid the need for animal agriculture.

- Drought tolerance (2028): Increasingly important for maintaining cropping in areas affected by climate change

- Paraquat Tolerance (2030): The final frontier in the fight against resistance

- African crops - acceptance of GM in EU and Africa (2030): Benefits of GM traits leapfrog into common food staple crops in Africa like Sorghum, Teff and Millet

- Golden Rice Adoption (2030): Vitamin A enhanced rice introduced into developing countries, with the potential to save 3M deaths per year from Vitamin A deficiency

- C3/C4 (2040): Converting C3 plants (rice and soybean) to highly productive C4 type (maize). C4 plants have a more complex photosynthesis process and fix more carbon during the growing process and are more productive. This will be a massive yield boost for existing c3 plants.

- Better understanding of Protein Folding (2050): Plants presently can't be used to produce protein-based therapeutic drugs for humans (such as insulin) because whilst they can be engineered to produce the protein, it is a folder in a different way to humans. We are rapidly understanding protein folding better; as soon as we can engineer plants to fold proteins in an equivalent way to humans, then huge opportunities are available to farm human medicine.

Terminology

- Variety is a specific genetic line that has been improved by plant breeders and genetically stabilized for commercialization. A variety will belong to a seed company and any one variety will have a lifetime between a couple of years and a decade. An example variety is P9492AM which is a Pioneer seed variety in Pioneers hybrid family P9492.

- Genetic Modification is a technique of editing the genome of a plant in a way that couldn’t be achieved by conventional breeding. Often using genetic code from a different species.

- Trait is the term given to describe a specific phenotypical feature (usually beneficial) which is expressed by the organism. For example, blue eyes is a trait in humans, whilst glyphosate herbicide resistance is a trait in a corn plant.

- Trait Brand is typically a trademarked name given (for branding and convenience) to a trait that has been discovered, commercialized and protected by a biotech company (eg. RoundupReady). The brand will be familiar to farmers, and has a lifetime measured in decades, depending on how long the trait remains competitive.

- Event is a term to describe the insertion of a particular transgene into a specific location on a plant chromosome – an event leads to the plant exhibiting the trait.

References

[1] McDougall P. The cost and time involved in the discovery, development and authorization of a new plant biotechnology derived trait (2011). https://croplife.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Getting-a-Biotech-Crop-to-Market-Phillips-McDougall-Study.pdf

Hickey et all 2019

Crain, J.; Mondal, S.; Rutkoski, J.; Singh, R.P.; Poland, J. Combining High-Throughput Phenotyping and Genomic Information to Increase Prediction and Selection Accuracy in Wheat Breeding. Plant Genome 2018

https://www.cimmyt.org/news/digital-imaging-tools-make-maize-breeding-much-more-efficient/

Tradespace Pictures: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hM8mV2bKOZM

https://iowaagliteracy.wordpress.com/2015/12/15/grain-drying-why-do-they-do-that/