Humanoid Robot Roadmap

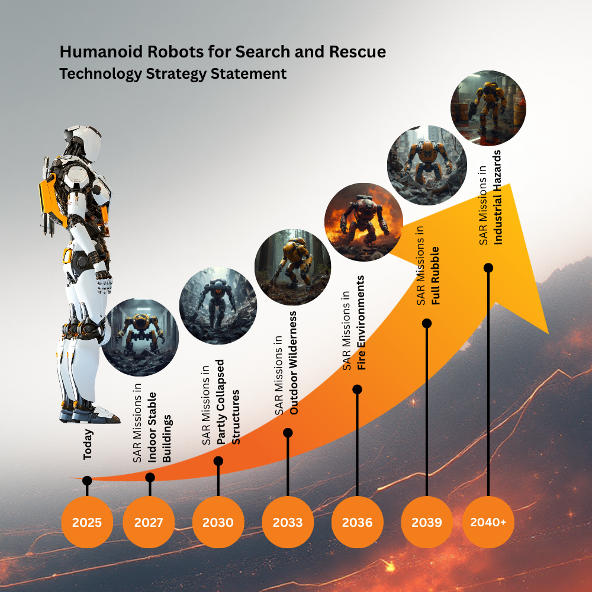

¶ Humanoid Robots for Search and Rescue (2HSR)

¶ 1. Roadmap Overview

Humanoid robots for Search and Rescue (2HSR) are robotic systems designed to operate in environments that are dangerous, unstable, or hard to reach for human responders. Although humanoid robots can be used across many industries, this roadmap focuses specifically on search and rescue scenarios, where the robot must move through human-oriented spaces after an incident and support or replace human teams in mission-critical operations.

Search and Rescue environments differ fundamentally from industrial or logistics settings. Collapsed buildings, unstable debris, narrow corridors, damaged staircases, and unpredictable terrain are all environments originally designed for people, but often degraded after an incident. These constraints make humanoid morphology uniquely suited for SAR, since it allows the robot to navigate, manipulate, and interact with infrastructure built for humans without requiring modifications to the environment.

Humanoid robots resemble the human body, featuring two legs, two arms, a torso, and a head-like structure. This design enables them to navigate spaces originally created for people. Their unique advantage in SAR missions is the ability to use existing human infrastructure, such as stairs, doors, tools, safety equipment, and workspace layouts, without needing significant modifications to the environment.

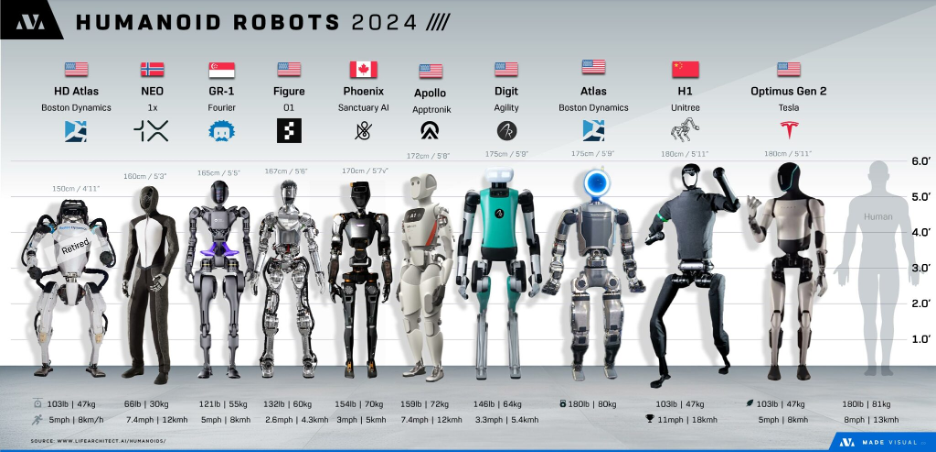

Some example implementations of such robots are pictured above [1]. We chose the Boston Dynamics’ Atlas: https://bostondynamics.com/atlas/ as the primary reference architecture.

Historical context

The concept of humanoid machines has been around for centuries, beginning with early automata in ancient Greece and continuing through the Middle Ages. Modern prototypes, such as WABOT-1 (developed in 1973 at Waseda University) and Honda's ASIMO (which debuted in the 2000s), showcased the feasibility of humanoid robots, though they were limited in mobility, autonomy, and practical applications.

A significant advancement in dynamic locomotion was achieved with Boston Dynamics' Atlas, which has been in development since 2013. Atlas demonstrated impressive capabilities, including running, jumping, and manipulating objects in complex environments.

Recently, companies like Tesla (with their Optimus model), Agility Robotics (known for Digit), and Figure AI have entered the humanoid robotics field, marking the beginning of commercialization in this area. However, these platforms are mostly optimized for structured or semi-structured industrial environments, which differ substantially from SAR conditions. For hazardous and unpredictable SAR missions, additional capabilities, ruggedization, high ingress protection, extended runtime, thermal resistance, and advanced sensing, are required..

Application categories

Humanoid robots are being developed for several categories of use, and among them, applications with the highest relevance to search and rescue include:

- Inspection and hazardous environments: nuclear plants, disaster response, oil & gas, where human presence is risky.

- Industrial and logistics support: transporting goods, loading/unloading, handling tasks alongside human workers.

- Service and healthcare: assisting elderly care, rehabilitation, and physical support in shared living spaces.

- General-purpose labor: replacing or augmenting human tasks in factories, warehouses, and even households.

- Outdoor search scenarios: cluttered terrain, uneven surfaces, and tight passages where wheeled robots cannot operate.

Other applications (elderly care, general domestic assistance, or warehouse logistics) remain out of scope except when they provide enabling technologies relevant for SAR.

Drivers of development

- Advances in control theory and AI enabling dynamic balance and predictive decision-making.

- Improvements in battery technology and lightweight actuators extending operating time.

- Progress in perception systems (vision, LiDAR, tactile sensors) allowing safe navigation around humans.

- Increased industrial and public-sector interest in reducing human exposure to hazardous conditions.

Challenges ahead

- Energy efficiency: humanoids remain power-hungry compared to wheeled robots.

- Safety and reliability: interaction with humans demands extremely low incident rates, or even zero high level accidents.

- Cost of manufacturing: complex actuators and sensors make humanoids expensive compared to task-specific robots.

- Integration with workflows: SAR missions require coordination with human teams under time pressure.

Roadmap outlook

The development trajectory is moving from research prototypes (proof of technology) to pilot deployments in logistics and industrial inspection (proof of value) to future specialized deployment in SAR scenarios. In the next decade, humanoid robots are expected to evolve from demonstrations to meaningful roles in shared spaces, including unstable buildings, uneven terrain, and outdoor rescue missions, driven by improvements in operating time, payload, safety certifications, and environmental robustness.

Overall, this roadmap positions humanoid systems not as general-purpose platforms, but as specialized, safety-critical tools designed for extreme environments. The trajectory reflects both the constraints of SAR missions and the technical dependencies, establishing a coherent path from current research capabilities to real-world deployment.

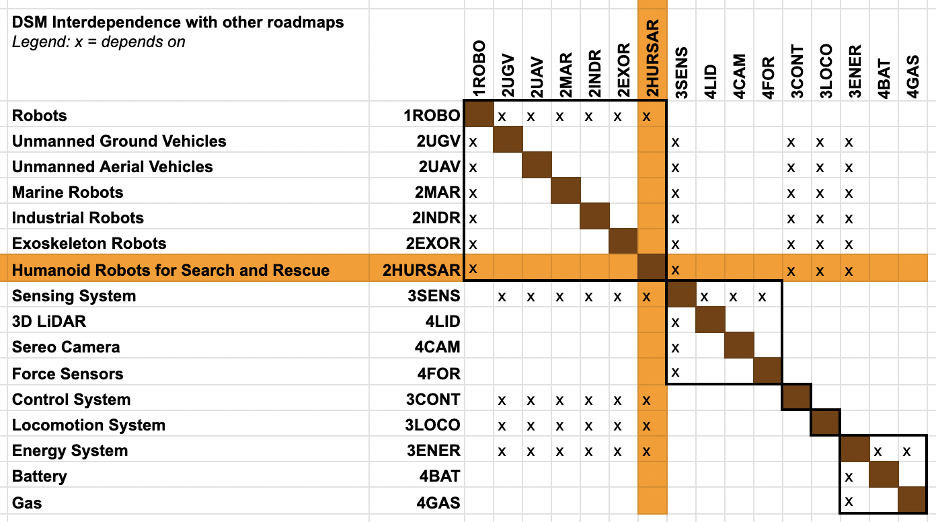

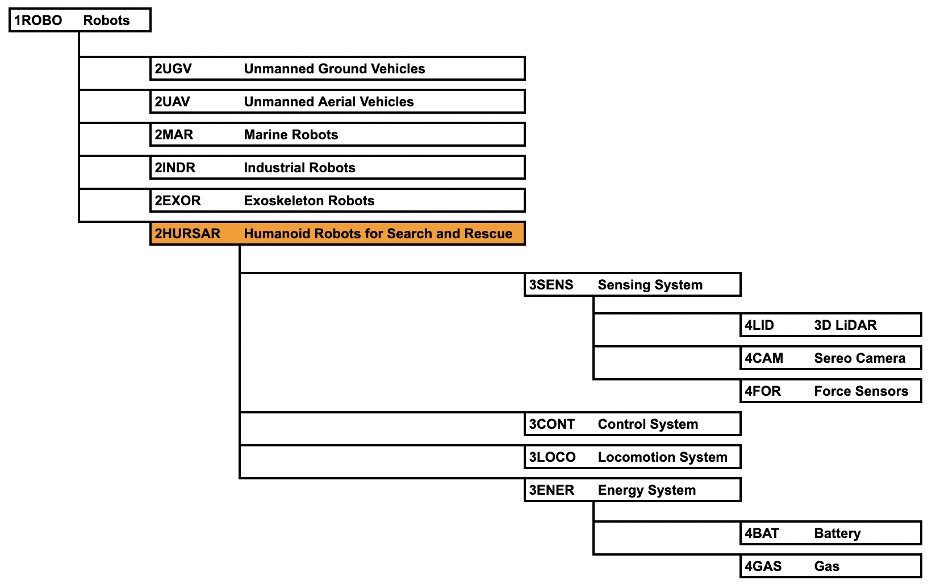

¶ 2. Design Structure Matrix (DSM) Allocation

The DSM below organizes the main categories of robotic systems together with the subsystems that make them work. It shows how different types of robots, ground, aerial, marine, industrial, exoskeletons, and humanoids for search and rescue, are connected through common enabling technologies such as sensing, control, locomotion, and energy systems.

Progress in one subsystem frequently impacts several others. Improvements in batteries or high-density energy sources extend operational time across multiple robot classes. Advances in sensing, such as new generations of 3D LiDAR, stereo vision, force sensing, or radar, enhance perception and reliability for both autonomous and semi-autonomous platforms. These linkages reflect the interconnected nature of robotics technologies.

For humanoid SAR systems (2HSR), these dependencies become substantially more pronounced. Operating in unstable debris, narrow passages, and partially collapsed structures requires tight integration between locomotion, manipulation, and sensing. Real-time perception must feed directly into whole-body motion planning to maintain balance and stability on unpredictable terrain. Actuation demands also remain high due to lifting, climbing, and load-bearing tasks.

Within the DSM, three clusters of interdependent technologies are particularly relevant for 2HSR:

Perception–Control: fusion of LiDAR, stereo vision, IMUs, tactile sensing, and environmental mapping to support stable motion and hazard detection.

Control–Locomotion: continuous adaptation of gait, foot placement, and whole-body posture for uneven or shifting terrain.

Energy–Actuation: high torque requirements for legs and arms drive significant energy consumption, influencing endurance and mission time.

These clusters frame the architectural constraints that shape humanoid SAR systems. Improvements in any of these areas propagate across the robot’s architecture and have direct implications for terrain adaptability, stability, and mission effectiveness.

Although many subsystems in the DSM appear across multiple robot types, humanoid robots for SAR rely on several dependencies that are significantly more pronounced compared to UAVs, UGVs, or industrial robots. In particular, the tight integration between bipedal locomotion and full-body manipulation (legs, arms, hands, and feet operating together) is unique to humanoids. These coupled subsystems enable capabilities such as climbing, stabilizing on uneven structures, opening doors, or clearing debris, tasks that require coordinated whole-body motion. This stronger dependency pattern explains why 2HSR systems exhibit higher architectural rigidity and why improvements in sensing, locomotion, or actuation tend to cascade across the system rather than remaining localized.

Some of the published roadmaps can also be linked to these technologies:

- 1ROBO - Robots

- [3AMR] - Autonomous Mobile Robots for Enhancing Warehouse Logistics

- 2MAR - Marine Robots

- [2AUV] - Autonomous Underwater Vehicles

- 2UGV - Unmanned Ground Vehichles

- [2ASGT] - Autonomous System for Ground Transport

- 3CONT - Control System

- 3SENS - Sensing System

- 4BAT - Battery

¶ 3. Roadmap Model using OPM

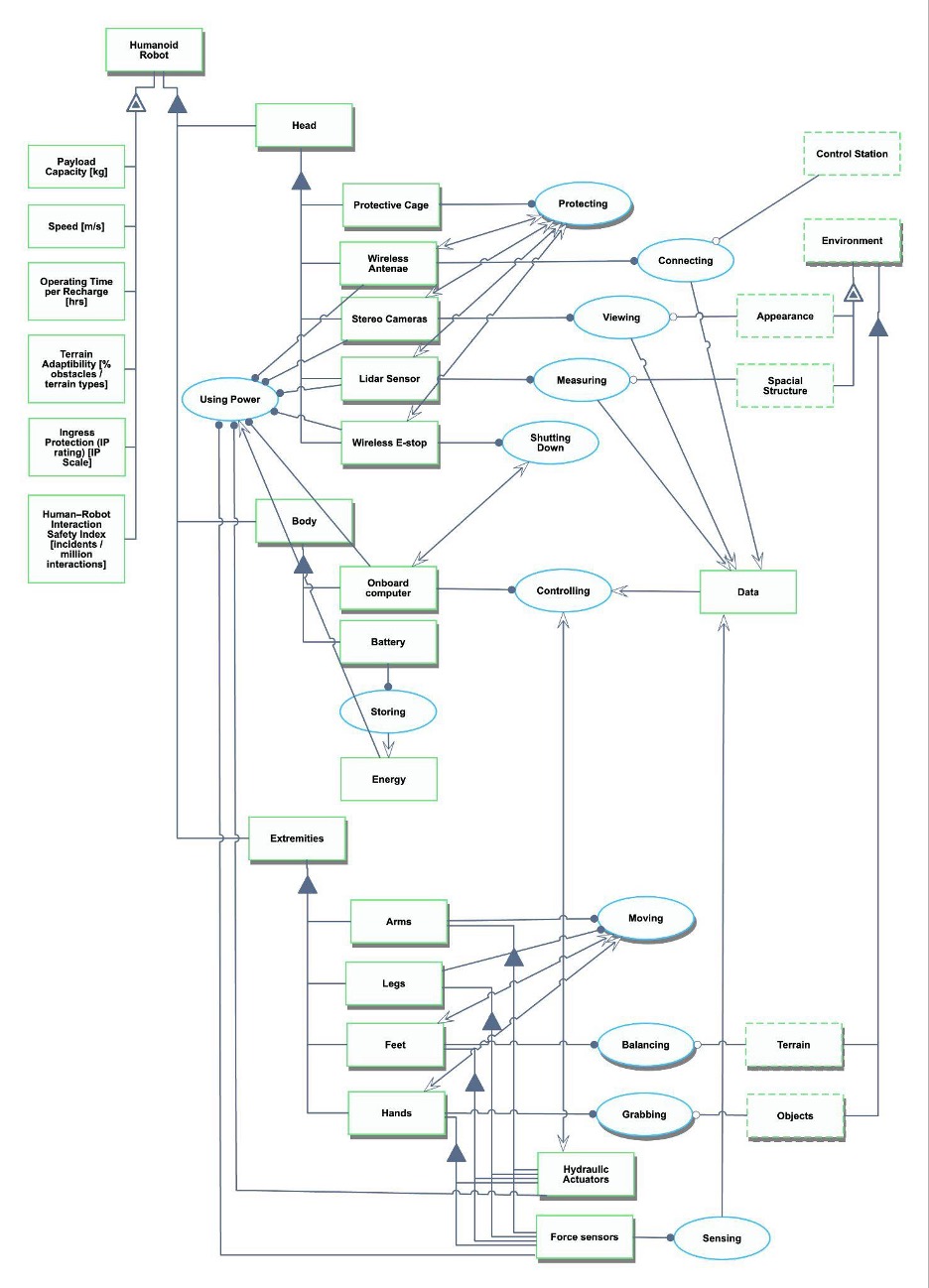

The OPM diagram below represents the structure and behavior of the humanoid robot designed for search and rescue missions. It organizes the system into its main components, head, body, and extremities, and the processes that connect them, such as moving, sensing, protecting, and controlling. Each element contributes to how the robot interacts with the environment, performs tasks, and maintains stability and safety while operating in hazardous conditions.

The allocation of components in the OPM model reflects functional relationships rather than strict physical placement. For example, the wireless e-stop is shown under the head subsystem because it interacts closely with sensing and communication processes, although in a real robot it could also be implemented in the torso or central electronics. The OPM representation captures the logical flow of operations rather than enforcing physical location.

Several of the attributes shown on the left side of the diagram represent Figures of Merit (FOMs), such as payload capacity, speed, terrain adaptability, operating time, and the human–robot interaction safety index. These are connected to the system as measurable performance outcomes derived from the robot’s structure and processes.

Sensors as LiDAR, stereo cameras, and force sensors feed data into the control system, allowing the robot to measure, balance, and adapt to any type of environments. The processes of protecting, viewing, and grabbing close the loop between perception and action, ensuring safe operation in unpredictable conditions. The model also links the system’s performance to measurable outcomes such as payload capacity, speed, terrain adaptability, and safety index.

In SAR environments, disturbances such as debris, dust, smoke, or unstable ground constantly influence the robot’s behavior. Locomotion, sensing, and protection must therefore operate as an integrated loop rather than as isolated modules. The OPM captures this interdependence by showing how perception feeds control, how control drives actuation, and how protection maintains sensor and system integrity during operation.

OPL for the 2HSR

- Humanoid Robot consists of Body, Extremities, and Head.

- Head consists of Lidar Sensor, Protective Cage, Stereo Cameras, Wireless Antenae, and Wireless E-stop.

- Body consists of Battery and Onboard computer.

- Extremities consists of Arms, Feet, Hands, and Legs.

- Energy is an informatical object.

- Data is an informatical object.

- Control Station is an informatical and environmental object.

- Feet consists of Force sensors and Hydraulic Actuators.

- Hands consists of Force sensors and Hydraulic Actuators.

- Legs consists of Force sensors and Hydraulic Actuators.

- Arms consists of Force sensors and Hydraulic Actuators.

- Environment consists of Objects and Terrain.

- Spacial Structure of Environment is an informatical and environmental object.

- Environment exhibits Appearance and Spacial Structure.

- Appearance of Environment is an informatical and environmental object.

- Payload Capacity of Humanoid Robot is an informatical object.

- Speed of Humanoid Robot is an informatical object.

- Operating Time per Recharge of Humanoid Robot is an informatical object.

- Terrain Adaptibility of Humanoid Robot is an informatical object.

- Ingress Protection of Humanoid Robot is an informatical object.

- Human–Robot Interaction Safety Index of Humanoid Robot is an informatical object.

- Humanoid Robot exhibits Human–Robot Interaction Safety Index, Ingress Protection, Operating Time per Recharge, Payload Capacity, Speed, and Terrain Adaptibility.

- Storing is an informatical process.

- Battery handles Storing.

- Storing yields Energy.

- Using Power is an informatical process.

- Force sensors, Hydraulic Actuators, Lidar Sensor, Onboard computer, Stereo Cameras, Wireless Antenae, and Wireless E-stop handle Using Power.

- Using Power consumes Energy.

- Shutting Down is an informatical process.

- Wireless E-stop handles Shutting Down.

- Shutting Down affects Onboard computer.

- Viewing is an informatical process.

- Stereo Cameras handles Viewing.

- Viewing requires Appearance of Environment.

- Viewing yields Data.

- Measuring is an informatical process.

- Lidar Sensor handles Measuring.

- Measuring requires Spacial Structure of Environment.

- Measuring yields Data.

- Connecting is an informatical process.

- Wireless Antenae handles Connecting.

- Connecting requires Control Station.

- Connecting yields Data.

- Hands handles Grabbing.

- Grabbing requires Objects.

- Controlling is an informatical process.

- Onboard computer handles Controlling.

- Controlling affects Hydraulic Actuators.

- Controlling consumes Data.

- Arms and Legs handle Moving.

- Moving affects Feet and Hands.

- Protective Cage handles Protecting.

- Protecting affects Lidar Sensor, Stereo Cameras, Wireless Antenae, and Wireless E-stop.

- Feet handles Balancing.

- Balancing requires Terrain.

- Sensing is an informatical process.

- Force sensors handles Sensing.

- Sensing yields Data.

¶ 4. Figures of Merit (FOM)

Below are key FOMs for humanoid robots. Operating time, speed, and payload capacity are critical for productivity. Robustness is captured by terrain adaptability and IP ratings, since humanoids are expected to work in industrial or outdoor environments. Safety of interaction with humans is also fundamental for their adoption.

The FOMs listed here represent measurable system-level outcomes rather than architectural decisions. They were selected because they describe external performance in SAR missions, such as endurance, payload, safety, and robustness, rather than internal design choices like joint mechanisms, actuator type, or materials. This distinction ensures the FOMs remain focused on mission effectiveness rather than subsystem architecture.

For clarity, the chosen FOMs can also be grouped into three categories:

• Performance (Payload, Speed, Operating Time)

• Environmental robustness (Terrain Adaptability, Ingress Protection)

• Human interaction & safety (Human–Robot Interaction Safety Index)

These FOMs also exhibit well-known trade-offs observed across past generations of humanoid and legged robots. For example, improving payload or mobility often reduces operating time due to energy demand. Improving ingress protection typically increases weight due to extra materials needed and increasing sensor sophistication adds computational load that impacts endurance. Historically, platforms like Atlas, Digit, and Optimus show gradual improvements in speed, autonomy, payload, and endurance as a result of advances in batteries, actuators, and perception systems.

The FOMs table is not presented in strict order of importance, since priorities shift across SAR environments. However, endurance, payload, and safety typically dominate mission success in most use cases.

| Figure of Merit | Unit | Description | Trend |

| Payload Capacity | [kg] | Maximum weight the humanoid can carry or manipulate safely while maintaining balance. | Increasing |

| Speed | [m/s] | Average locomotion speed of the humanoid in human environments such as factories or warehouses. | Increasing |

| Operating Time per Recharge | [hrs] | Total time the humanoid can operate on one full charge before recharging or swapping batteries. | Increasing |

| Terrain Adaptability | [% obstacles / terrain types] | Ability to traverse stairs, ramps, uneven or cluttered ground without failure. | Increasing |

| Ingress Protection (IP rating) | [IP scale] | Dustproof and waterproof resistance according to IEC standards, relevant for industrial environments. | Increasing |

| Human–Robot Interaction Safety Index | [incidents / million interactions] | Measures safety and reliability in shared spaces, minimizing accidents with human workers. | Decreasing (improving) |

Table 2: Figures of merit for the Humanoid Robot for Search and Rescue

Each FOM has an estimated dFOM/dt (rate of change) informed by previous generations of robots and correlated technologies (e.g., batteries, control algorithms, lightweight materials). These trends will be used to project the next 5–10 years of humanoid development and assess when they may become competitive in shared human environments.

¶ 5. Alignment of Strategic Drivers: FOM Targets

Company Overview:

HURSAR Technologies is a hypothetical startup specializing, created for the matter of EM.427, in humanoid robotic systems designed for search and rescue in hazardous or hard-to-reach environments. Our strategic vision is to extend human capability and safety through autonomous or distance controlled robotics that can operate in environments unfit for human workers.

To reduce implementation costs and enable the go to market strategy, an easy interaction platform will be designed and full knowledge training will be provided to enable each user to be able and responsible to deploy the technologies, enabling rollout all around the globe and increasing potential market.

To strengthen the connection between our technology strategy and the specific needs of Search and Rescue (SAR) missions, each strategic driver below is framed by the operational challenges observed in real SAR scenarios: unstable terrain, unpredictable environmental hazards, long-distance missions, limited visibility, and the critical need to avoid injuries or collateral damage during rescue operations.

Strategic Drivers and FOM Alignment:

- Safety & Reliability – Ensure zero severe incidents in human-robot collaboration during tests, missions, deployment, etc (Human–Robot Interaction Safety Index < 0.1 incidents / million interactions by 2030). In SAR operations, teams work in confined, chaotic, partially collapsed structures where an unsafe interaction could injure both rescuers and victims. Reliability is not only a product requirement, it is a core mission requirement since a robot failure inside rubble or high-risk areas directly jeopardizes human lives.

- Operational Endurance – Extend mission time for autonomy in rescue operations (Operating Time per Recharge ≥ 6 hours). SAR missions often take place far from reliable power sources and require extended search paths through rubble, wilderness, or large indoor complexes. Longer endurance directly expands the effective search radius and reduces the number of human deployments into danger zones.

- Environmental Robustness – Guarantee reliable performance in harsh and variable terrain (Terrain Adaptability ≥ 90% / IP67 rating). Environmental variability is significantly higher in SAR than in industrial settings for the nature of the work. Robots face dust, water, debris, mud, smoke, and moving unstable surfaces. Robustness is therefore directly connected to the robot’s ability to stay operational throughout the entire mission, not just under controlled conditions.

- Mobility & Performance – Achieve human-equivalent locomotion and manipulation (Speed ≥ 1.5 m/s / Payload ≥ 25 kg). Unlike warehouse or factory robots, SAR humanoids must climb, crawl, step over obstacles, and carry tools or medical supplies. Payload and mobility directly affect their ability to perform meaningful rescue tasks rather than being passive observers.

- Affordability & Scalability – Reduce system cost to enable broader deployment (Cost ≤ USD 150k per unit already deployed). SAR organizations worldwide (fire departments, FEMA teams, military rescue units) typically operate under tight procurement budgets. A high-performing but unaffordable robot limits global adoption and reduces real-world impact. Affordability is therefore a strategic enabler for large-scale humanitarian benefit.

Each Figure of Merit (FOM) maps directly to at least one strategic driver and, together, they define the systems operational maturity for real rescue deployments. This integration ensures that improvements in energy, mobility, safety, and robustness are aligned with what SAR organizations require in the field, allowing HURSAR to progress from prototype to certified field equipment by 2030.

¶ 6. Positioning of Organization vs. Competition: FOM charts

The humanoid robotics market is currently led by Boston Dynamics (Atlas), Tesla (Optimus), Agility Robotics (Digit), and Figure AI. Almost all of them are not ready to market, so they are still "under development" or in test studies or they are planned to be for research only. HURSAR Technologies positions itself between research-grade agility and industrial robustness, combining endurance, environmental resistance, and field readiness. The main goal is to have a go-to-market strong strategy and position as a company that delivers value over only research.

It is important to note that none of the leading commercial humanoid companies today are targeting Search and Rescue missions specifically. Their use cases focus on general-purpose tasks or structured industrial environments. This makes direct comparison difficult, and it is exactly why our positioning emphasizes SAR-oriented FOMs (IP rating, terrain adaptability, safety index, endurance), which are not priorities for most current competitors.

Competitive Positioning (FOM-based narrative):

- Speed: Tesla Optimus (≈ 2 m/s) and Atlas (≈ 1.5 m/s) lead; HURSAR targets parity at 1.5 m/s. The speed is not understood by us as a differential as the main purpose is safe and rescue in hard areas where high locomotion speed is not required. In SAR environments, stability and precision matter more than raw speed. Maintaining parity ensures functional mobility without compromising safety.

- Payload Capacity: Atlas (11 kg), Digit (16 kg); HURSAR aims for 25 kg to support mission tools. This must be one of the main differentials. Payload directly translates to SAR usefulness: carrying medical kits, sensors, breaching tools, or transporting supplies through collapsed structures.

- Operating Time: Current humanoids average 1–2 hours; HURSAR targets 6 hours via Li-air battery integration. Main challenge as the battery technology today is a constrain. Recharge 50/50 cicle will be the same as Boston Dynamics. Extended endurance is crucial in SAR missions where robots may need to cover large search areas without immediate access to charging or extraction points.

- Terrain Adaptability: Atlas and Digit handle ~80% of common terrains; HURSAR aims at 90%. SAR environments include rubble, unstable debris, outdoor wilderness, and flooded or contaminated areas, conditions under which most commercial humanoids are not designed to operate as they are for industrial use.

- Ingress Protection (IP): Atlas unsealed; HURSAR will achieve IP67 for hazardous sites. Water, dust, chemical exposure and smoke are typical SAR hazards, sealing is mandatory for real deployments but is not addressed by most competitors, even being requirement from many industries these days.

- Safety Index: Commercial humanoids not yet certified; HURSAR roadmap includes ISO 10218 & ISO 15066 compliance. This is to ensure that HURSAR can run closely with people in any condition as described by ISO 10218. Shared-space rescue operations often place robots next to victims and rescue workers in tight locations, demanding safety standards above typical industrial robots, even being true that industrial robots operate close with humans.

This positioning illustrates a 'value-through-robustness' strategy: rather than optimizing for consumer or lab performance, HURSAR focuses on deployability and operational reliability, the key differentiators for mission-critical robotics and with strong strategy to field customer based operations.

In short, while most competitors pursue general-purpose humanoids, HURSAR explicitly optimizes for the extreme environments and life-critical reliability demanded by SAR missions. This strategic focus forms a unique market position and clarifies why our selected FOM targets matter more for SAR than traditional performance metrics used by other humanoid developers.

¶ 7. Technical Model: Morphological Matrix and Tradespace

Morphological Matrix:

| Function / Subsystem | Option 1 | Option 2 | Option 3 |

| Actuation Type | Hydraulic | Electric | Series Elastic / Hybrid |

| Energy Source | Li-ion Battery | Solid-State Battery | Li-Air Battery (future concept) |

| Control Architecture | Centralized | Distributed | Cloud-Assisted |

| Perception Suite | Stereo Vision | Vision + LiDAR | Multi-Modal (Tactile + LiDAR + Thermal) |

| Material System | Aluminum Alloy | Carbon Fiber | Composite / Lightweight Polymer |

| Autonomy Level | Tele-operated | Semi-Autonomous | Fully Autonomous (Adaptive AI) |

Table 3: Morphological Matrix

This morphological matrix defines the design space for the HURSAR humanoid robot, outlining possible configurations across its major subsystems.

Early-stage prototypes (2025–2027) are expected to rely primarily on electric actuation powered by Li-ion batteries, with a semi-autonomous control architecture.

As the technology matures toward 2030, hybrid actuation and Li-air batteries will extend mission endurance, while autonomy evolves toward adaptive AI-based decision-making.

Tradespace and Design Relationships

The tradespace analysis focuses on the interplay among three primary Figures of Merit (FOMs):

- Operating Time per Recharge (hours)

- Payload Capacity (kg)

- Autonomy Level (qualitative index)

Key Observations

1. Energy vs. Payload Trade-off:

Increasing energy density (via Li-air or hybrid systems) directly extends operating time but adds weight and thermal management challenges, slightly reducing payload capacity.

2. Autonomy vs. Complexity:

Higher autonomy (transition from semi- to fully autonomous) increases mission efficiency but significantly raises system complexity and computational power requirements, impacting energy consumption.

3. Material vs. Durability:

Lightweight composites enhance endurance and mobility but reduce impact resistance and structural stiffness compared to metallic designs.

4. Power vs. Control Precision:

Hydraulic systems provide greater power and robustness for manipulation but consume more energy and complicate maintenance; electric and hybrid systems trade some force output for higher efficiency and smoother control.

Tornado Chart - FOM Sensitivity for HURSAR:

Tradespace: Energy vs. Payload Trade-off

Conclusion Summary

This technical model provides a structured and well organized way to evaluate system configurations and sensitivities for HURSAR humanoid robots.

The morphological matrix captures the key design choices with all the key design options to our chosen technology; the tradespace analysis identifies where technological innovation offers the greatest leverage and advantages for each FOM.

Together, these tools guide future development priorities, balancing energy efficiency, autonomy, and payload capacity within realistic engineering and operational constraints. The cost and availability of each one of these technologies will be further discussed and analyzed.

¶ 8. Financial Model: Technology Value (𝛥NPV)

The document below outlines the financial model for the HURSAR Project.

Technology Product Consumers

The objective of the HURSAR project is to improve the outcomes of Search and Rescue (SAR) missions through the use of Humanoid Robots. As such, key consumers of the product produced through this research are SAR companies such as the US Government (FEMA Urban Search & Rescue Task Forces), other international governments (Japan International Search and Rescue Team, UK International Search and Rescue Team, Germany THW etc), Fire Departments (such as FDNY), Wilderness rescue organizations (National Park Service SAR teams). The financial model is structured such that the company produces HURSAR units and sells them to organizations such as these.

To clarify the logic of this financial model, each “phase” corresponds directly to the technical evolution presented in previous sections (FOM improvements, R&D milestones, and TRL progress). These phases are not market-arbitrary, in contrary, each one represents a specific environment becoming feasible only after certain technological capabilities mature, such as improved perception, higher IP ratings, better autonomy or enhanced stability.

Development Phases

Search and Rescue can be performed in a range of environments. For more accurate financial modeling, the technical roadmap can be broken down into the following phases of environmental operation:

- Indoor Stable Buildings

- Partially Collapsed Structures

- Outdoor Wilderness

- Fire Environments

- Full Rubble Structures

- Industrial Hazards

These development phases are based on an estimation of demand for these different SAR scenarios and technical complexity. They are later used in determining the plan for R&D projects.

This environment-based phasing mirrors the real adoption curve for SAR technologies: simpler indoor scenarios represent early TRL-7 deployments, while high-hazard environments such as fires, rubble, or industrial chemical zones represent TRL-9 maturity. This framing helps connect technical feasibility with market entry potential in a disciplined manner.

Financial Assumptions

The table below provides an estimated selling price per unit and cost for production of each phased release of robot:

| Phase | Environment | Sale Price per Unit | Cost per Unit | Annual Units Sold |

Release Date |

| 1 | Indoor Stable Buildings | $160k | $110k | 900 | 2027 |

| 2 | Partially Collapsed Structures | $240k | $135k | 600 | 2030 |

| 3 | Outdoor Wilderness | $200k | $150k | 450 | 2033 |

| 4 | Fire Environments | $250k | $170k | 300 | 2036 |

| 5 | Full Rubble Structures | $300k | $190k | 150 | 2039 |

| 6 | Industrial Hazards | $350k | $220k | 40 | 2040+ |

Table 4: Financial assumptions for each phased release of the HURSAR humanoid robot

The pricing and volume assumptions reflect procurement patterns from global SAR agencies, rather than consumer markets, as SAR agencies are the ones handling this type of product. SAR teams typically purchase units in small fleets as certifications and capabilities increase. Therefore, as technical capacity expands (through improved robustness, autonomy, or heat resistance), the market narrows but value per unit increases.

The table below estimates the R&D budget for each phased release of robot:

(Please see list of R&D Projects for more details)

| Environment | R&D Project | R&D Cost | Date |

| Indoor Stable Buildings | Person detection | $5M | 2026 |

| Indoor traversal and simple manipulation | $6M | 2027 | |

| Partially Collapsed Structures | Thermal and dark perception | $8M | 2028 |

| Semi-autonomous navigation & debris clearing | $10M | 2030 | |

| Outdoor Wilderness | Outdoor weather resistance | $7M | 2031 |

| Semi-autonomous GPS & Terrain navigation | $9M | 2033 | |

| Fire Environments | Heat shielded resistance and safety | $11M | 2034 |

| Improved sensing for navigation in fire | $10M | 2036 | |

| Full Rubble Structures | Autonomous confined space navigation | $12M | 2037 |

| Autonomous debris clearing | $14M | 2039 | |

| Industrial Hazards | Full body sealing and decontamination | $10M | 2040 |

Table 5: R&D investment profile aligned with each environmental capability phase of the HURSAR roadmap.

Please note all financial estimates above were generated through ChatGPT.

For the purposes of this financial model it is assumed that the previous phase units continue to be sold as new phases are released.

This “rolling availability” assumption reflects real robotics procurement, where earlier functional variants remain in use (and commercially relevant) even after more advanced platforms are released. This reduces the risk of revenue interruptions and aligns with how SAR organizations mix legacy and next-generation equipment.

Financial Calculation of NPV

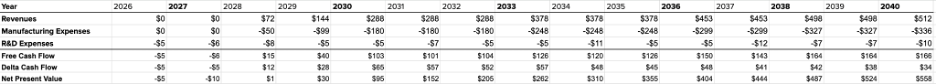

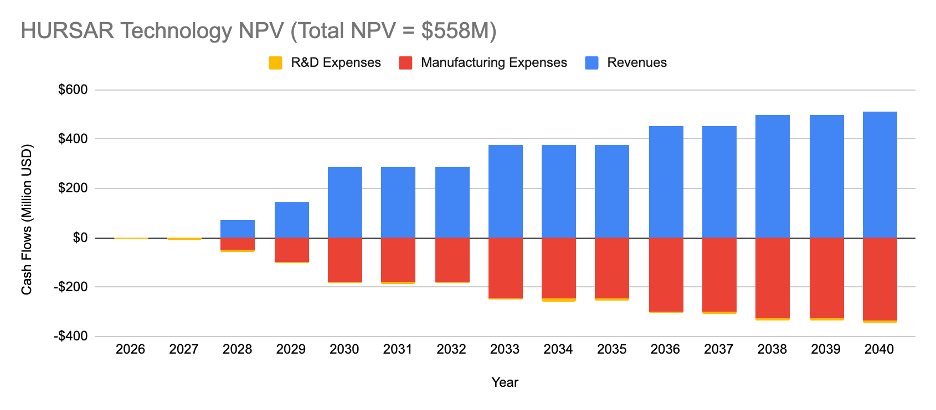

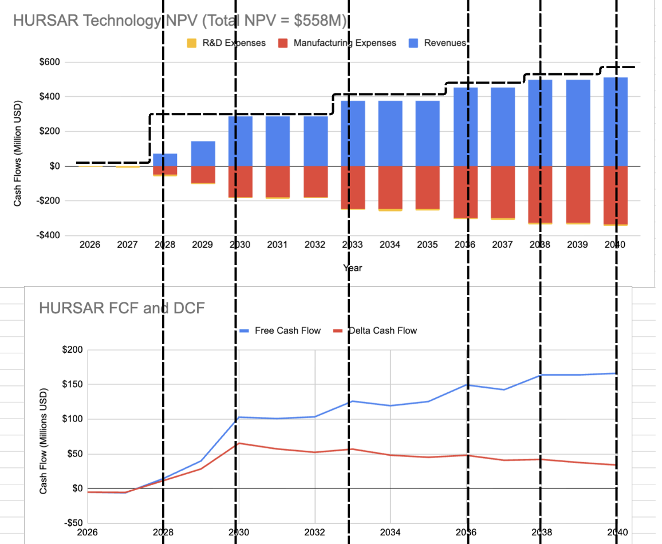

Using this data we can calculate the Free Cash Flow (FCF), Delta Cash Flow (DCF) and Net Present Value (NPV) using this data.

Table 6: Annual Financial Breakdown for HURSAR Phased Development (2026–2040)

The NPV progression is closely tied to the technical roadmap. Each major R&D investment unlocks a new operational environment, which in turn enables a new revenue stream. Therefore, increases in cumulative cash flow are directly linked to technology releases rather than purely financial timing.

This chart shows the strategy of continuing to invest in R&D as the units begin to be produced. Note that there isn’t a drastic spike at the beginning of R&D development comparatively because it is assuming that the Humanoid Robot is already built and this is building additional functionality for the Search and Rescue Functionality.

The stepwise changes in cash flow correspond to TRL milestones where a new capability becomes commercially deployable. Each “step” therefore represents the conversion of technological maturity into financial value.

It is interesting to note in the diagram below that the Phase released on these charts result in a step function change in cash flow. This is expected as more funding is poured into research and as more product is released to the market.

This reinforces the alignment between financial and technical planning. The business model grows only when technology performance reaches required thresholds for SAR deployment, ensuring that revenue projections are grounded in realistic capability progression.

Final Synthesis

In summary, the financial model is deliberately tied to the roadmap's technical development sequence. Each phase corresponds to a clearly defined environmental capability, each revenue increase is unlocked by an R&D deliverable, and each price uplift reflects an improved FOM. This ensures the financial view is not isolated from the technical view but evolves in lockstep with it.

¶ 9. List of R&D Projects and Prototypes

As stated on previous sections, the top strategic drivers were Safety & Reliability, Operational Endurance, and Environmental Robustness. Improvements to Safety and Reliability will be a core part of all R&D efforts, as new functionalities are added, these non-functional requirements will also be at the forefront of development. Operational Endurance is gated by the performance of the battery which is a direct dependency on a technology external to HURSAR. For this reason, our internal R&D effort focuses primarily on improving Environmental Robustness and Mission Capability across progressively more complex SAR environments.

Ultimately, Humanoid Robots for Search and Rescue need to operate in a variety of scenarios that are difficult or unsafe for humans. Depending on the environment, functional requirements such as sensing, balance, payload, and human–robot interaction are affected. Therefore, the R&D strategy follows a step-function improvement model, adding specialized functionality year over year. The table below summarizes the targeted environments and the corresponding system requirements.

| Phase | Environment | Functional Requirements | Target |

| 1 | Indoor Stable Buildings |

- Basic autonomous navigation - Person detection - Corridor traversal & safe movement - Door opening & simple manipulation |

2027 |

| 2 | Partially Collapsed Structures |

- Navigation in debris-filled spaces - Thermal imaging for person detection - Dust/darkness perception - Semi-autonomous debris clearing |

2030 |

| 3 | Outdoor Wilderness |

- GPS based long range navigation - Long-range thermal detection - Mesh-network communication - Weather-resistant components |

2033 |

| 4 | Fire Environments |

- Radar navigation through smoke - High-temperature housing for sensors - Gas detection (CO, VOCs) - Safe operation near fire zones |

2036 |

| 5 | Full Rubble Structures |

- Confined-space navigation - Structural vibration analysis - Autonomous debris clearing - Precision haptics for manipulation |

2039 |

| 6 | Industrial Hazards |

- Radiation detection - Chemical leak identification - Full body sealing + decontamination |

2040+ |

These phases are aligned with the demand patterns identified in the financial model and increase in technical complexity across SAR missions.

Based on this, the following table summarises the recommended R&D projects:

| Environment | R&D Project | Target |

| Indoor Stable Buildings |

Person detection Safely and accurately detect persons behind obstructions using a variety of sensors |

2026 |

|

Indoor traversal and simple manipulation Navigate through indoor spaces to the detected person using basic manipulation. |

2027 | |

| Partially Collapsed Structures |

Thermal and dark perception Improved perception in dark spaces and detection of thermal signals for victim detection |

2028 |

|

Semi-autonomous navigation & debris clearing Navigation in partially collapsed structures and clearing the path through debris |

2030 | |

| Outdoor Wilderness |

Outdoor weather resistance Improved Ingress Protection ratings as needed for outdoor environments |

2031 |

|

Semi-autonomous GPS based & Terrain navigation Navigation through forestry, rain, mud, slippery surfaces and challenging outdoor environments |

2033 | |

| Fire Environments |

Heat shielded resistance and safety Improved electronics and chassis for performance in high heat and active fire environments |

2034 |

|

Improved sensing for navigation in fire Radar navigation through smoke, high-temperature housing for sensors, Gas detection (CO, VOCs) |

2036 | |

| Full Rubble Structures |

Autonomous confined space navigation Fully autonomous navigation through confined spaces building on the previous navigation work |

2037 |

|

Autonomous debris clearing Clearing paths through full rubble structures |

2039 | |

| Industrial Hazards |

Full body sealing and decontamination Operation in radiation and chemical environments |

2040 |

¶ 10. Key Publications, Presentations and Patents

¶ 10.1 Publications & Presentations

1. Kajita et al., “Dynamic Walking Control for Humanoid Robots Based on the Linear Inverted Pendulum Model” (IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 2014)

This work introduced the Linear Inverted Pendulum Model (LIPM), the most widely used framework for humanoid balance and gait control. LIPM underpins how modern humanoids handle mass distribution, step placement, and center-of-mass control, fundamental for traversing rubble, unstable surfaces, and cluttered environments typical of SAR missions.

Relevance to roadmap: supports locomotion stability FOM, informs subsystem 3LOCO and 3CONT.

2. B. Katz et al. (2019). 'Optimization-Based Locomotion Planning for the Atlas Humanoid.' IEEE ICRA – model predictive control for perception feedback.

This paper details model predictive control (MPC) techniques applied to the Boston Dynamics Atlas robot. These techniques enable dynamic maneuvers such as leaping, balancing after disturbances, or adjusting steps in real time, essential behaviors for SAR where conditions change rapidly.

Relevance: informs high-agility locomotion, useful for TRL progression in phases 4–6.

3. Dai, Nian et al. ‘AI-assisted flexible electronics in humanoid robot heads for natural and authentic facial expressions.’ The Innovation, Volume 6, Issue 2, 100752

Although focused on expressive humanoids, this publication introduces sensor-dense facial structures and distributed tactile electronics. The sensing and materials concepts translate to SAR needs such as damage detection, soft impacts, and robust head-mounted instrumentation.

Relevance: improves sensing redundancy, environmental awareness, and safety index.

4. Hirose Masato and Ogawa Kenichi 2007Honda humanoid robots developmentPhil. Trans. R. Soc. A.36511–19

This historical review covers ASIMO’s locomotion, actuation, and perception systems. Many of the tradeoffs described: payload vs. stability, power consumption vs. speed, directly parallel challenges in SAR robots today.

Relevance: contextual benchmark for long-term actuation and control architecture choices.

5. Hussein & Terakado & de Weck, “Comprehensive Study of the International Space Launch Industry: Programmatic Analysis and Technical Failures” (Acta Astronautica, 2025)

Although from another robotics domain, this publication is included because of its analysis of failure modes, reliability modeling, and subsystem-driven fault propagation—critical concepts for defining SAR safety and reliability FOMs.

Relevance: informs reliability modeling and risk assessment frameworks.

¶ 10.2 Patents

The patents listed below were chosen because they provide concrete engineering insights into locomotion, sensing, actuation, environmental protection, and energy systems—all of which are required for a humanoid robot designed for search and rescue operations.

Each patent includes a short explanation of how it links to the HURSAR roadmap and DSM.

1. US 2019/0167564 A1 – 'Systems and Methods for Autonomous Locomotion of a Quadruped or Humanoid Robot' (Boston Dynamics). Describes control systems for coordinated leg motion.

Describes coordinated multi-limb locomotion control, including whole-body force modulation and dynamic stability.

Relevance: foundational for rubble traversal, balance recovery, and high-agility SAR movement.

Links to: 3LOCO, 3CONT, terrain adaptability.

2. US 2021/0123345 A1 – 'Battery Module Architecture for High-Performance Robots' (Tesla Inc.). Modular Li-ion pack design applicable to humanoid robots.

Introduces modular battery packs enabling rapid swapping, thermal management, and scalable capacity.

Relevance: directly supports Operating Time per Recharge and fast redeployment in field operations.

Links to: 4BAT.

3. US 2025/0333127 A1 – ‘Hip Joint of Humanoid Robot.’

Covers high-strength joint architecture and joint-driven balance compensation.

Relevance: core mechanical subsystem for load-bearing, stability during manipulation, and lifting tasks.

Links to: actuation system, payload capacity FOM.

4. US 12,449,822 B2 – ‘Ground Clutter Avoidance For A Mobile Robot’

Describes algorithms for identifying clutter and predicting safe traversal paths.

Relevance: essential for SAR environments where debris is constant. Directly supports navigation reliability and autonomy.

Links to: 3SENS, autonomy level.

5. US 2025/0334694 A1 – ‘Rotating Ultrasonic Field Of View Having Fixed Sensor’

Provides extended FOV sensing via ultrasonic actuated scanning.

Relevance: useful in smoke, dust, darkness. Conditions where optical sensors degrade.

Links to: multi-modal perception, environmental robustness.

¶ 11. Technology Strategy Statement

Our target is to develop a Humanoid Robot for Search and Rescue (SAR) missions by the year of 2040. While humanoid robots already exist in the industry today, these need to be adapted for the purpose of search and rescue and require additional development for suitable use in hazardous environments. To reach this target we will invest in a series of incremental R&D Projects of increasing complexity and for use in more complex environments.

Three main streams of R&D can happen in parallel:

- Navigation - Initially, improvements will be made in indoor navigation and person detection as needed for SAR missions. Navigation will incrementally be improved over the next several years through rubble and outdoor environments.

- Environmental Resistance - improved environmental resistance for outdoor weather, heat, debris and other hazards.

- Autonomy - Lastly R&D efforts in autonomy will improve the performance of the robot incrementally to reduce the needed human touch points.

Please note that battery performance improvements remain external to this roadmap; our developments will integrate advances as they become available.

The diagram below illustrates the phased evolution of technical capability across the targeted environments.